|

We live in a world full of signals. We are constantly bombarded with exciting new combinations of light, sound, taste, smell, and texture. Ultimately our brains interpret these sensations to form what we call reality. However, as it turns out, human beings are only able to perceive a small slice of reality: there are many smells which, for better or worse, we can never smell, and we can only see a tiny slice of the colors light has to offer (we refer to this small portion of wavelengths as the “visible spectrum”).

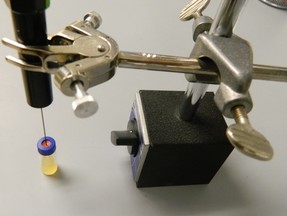

As it turns out, flies do not base their behavior on the smell of the fruit: they base it on the smell of the yeast growing on the fruit. When yeasts are removed from fruit, the flies do not know where to go. Dr. Syed’s team took a sample of yeasts abundant in fruit and associated SWD flies and found that SWD choose certain yeasts over others, but why? To answer this question, they sampled the odors that were produced by his yeasts using solid-phase microextraction (SPME) to see if they were different. They were in fact different – qualitatively and quantitatively - with each yeast isolate producing a very complex and wide range of odorant repertoire. Approaching the point of despair at interpreting all of his data, a statistician swooped in to save the day. The statistician was able to distinguish between the yeasts based solely on the odors they produce.

Read more about Dr. Syed’s Work

Scheidler, N. H., Liu, C., Hamby, K. A., Zalom, F. G., & Syed, Z. (2015). Volatile codes: Correlation of olfactory signals and reception in Drosophila-yeast chemical communication. Scientific reports, 5, 14059. Hickner, P. V., Rivaldi, C. L., Johnson, C. M., Siddappaji, M., Raster, G. J., & Syed, Z. (2016). The making of a pest: Insights from the evolution of chemosensory receptor families in a pestiferous and invasive fly, Drosophila suzukii. BMC genomics, 17(1), 648. About the author: Brian Lovett is a PhD student in Dr. Raymond St. Leger’s Lab studying mycology and genetics in agricultural and vector biology systems. He is currently working on projects analyzing mycorrhizal interactions in agricultural systems, the transcriptomics of malaria vector mosquitoes, and the genomes of entomopathogenic fungi. Brief Summary: At the first Entomology colloquium of the Spring 2017 semester, Dr. Zain Sayed described his work on the agricultural pest spotted wing drosophila. His work unravels how female flies use odors from yeasts growing on fruit to find their mates. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed