There is currently a decline in insect biodiversity, with many species going extinct at an unprecedented rate. The Endangered Species Act was put into law in 1973 to protect vulnerable plants and animals in the United States. There are 99 protected insect species, including representatives from within butterflies, beetles, and bees. The role that pesticides play in this massive loss of insects is currently unknown. In order to protect endangered organisms, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) conducts pesticide risk assessments. This includes insecticide assessments to understand the effects these products have on all protected insect species. However, the EPA has assessed risk to less than 5% of listed species. Additionally, the risk assessments of insecticides are done using honeybees as a model insect, meaning they are used as a stand-in for all insects. Due to the amazing variety in insects across orders, not all insects will react to an insecticide in a similar manner. To uncover where the results of risk assessments the EPA does for honeybees (Hymenoptera) are accurate to other orders, Undergraduate researcher Margaret Kato compared the EPA’s assessments to insecticide susceptibility in beetles (Coleoptera) for her honor’s thesis research at University of Maryland.

Kato started this independent research project as a sophomore in the Krishnan Lab (Entomology Department). While the Krishnan lab typically focuses on butterfly (Lepidoptera) susceptibility to insecticides, the Entomology Honors Program provides an opportunity for undergraduate students to do an independent research thesis and receive honors certification. Thus, Kato was able to go a different direction with her research, and focused her research on beetle insecticide toxicity testing and sensitivity.

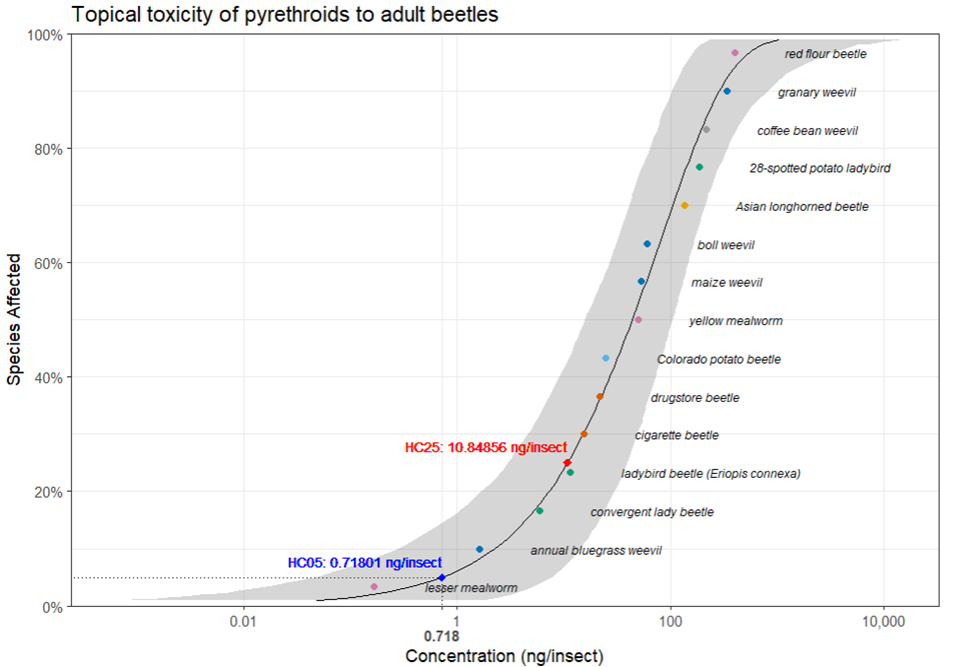

Even though the effect of insecticides on endangered insects would ideally be tested on the insects directly, it can be difficult to rear endangered insects in a lab to test their reactions to insecticides. However, methods to estimate the insecticide’s effect on a group of insects, such as beetles, allow us to make predictions about the effect of insecticides on endangered members of those groups. One such method is generating Species Sensitivity Distributions (SSDs). Kato creates (SSDs) by compiling lab-generated evidence for a group of ten well-studied beetle species (Fig. 1). The SSD for a given insecticide allows researchers to determine the range of its effects on beetles.

Because insecticides can be administered in so many different ways, it is also important to study the comparative effect of those methods of application. Insects can be exposed to insecticides topically (applied directly to the outside of their body), through consumption, or by touching a treated surface. Most available data examines topical and surface exposure. By creating SSDs for beetles, Kato determined that beetles are typically 200-4000 times more sensitive than honey bees to topical exposure, when compared in the context of the EPA's risk assessment guidelines. The variation in the increased sensitivity is largely due to which class of insecticide was used.

The SSDs and other measures of insecticide toxicity on beetles inform EPA guidelines around insecticide use such as their concentration and application. By understanding how various beetles respond to insecticides, the EPA can work to protect endangered beetles that are more difficult to study.

It is notable that Kato gave a department seminar while still an undergraduate; most speakers are people more established in their fields. She communicated her research effectively and knowledgeably fielded questions. The work accomplished by Kato as an undergraduate student furthers the field of insect toxicity sensitivity studies, while also being “very fun and influential” in her interests and future career plans. Her work as an undergraduate researcher has inspired an interest in insect toxicology, governmental regulation of pesticides, and the scientific process. Kato states that leading an independent project in the Entomology Honors Program is an “amazing experience” under her “fantastic and inspiring mentor,” Dr. Krishnan. Being a part of the program had a long-term effect on Kato’s interest and influenced her career path. She presented her results at the Entomological Society of America conference this month, and after graduation, she plans to pursue a PhD in bioinformatics.