Written by: Emma Hotchkiss

What draws a bee to a flower? Most bee-pollinated flowers provide nutritional incentives to attract a bee: sugary, carbohydrate-packed nectar and protein-rich pollen. These energetically expensive offerings lure many pollinators to the flower, with each visit increasing the chances that its pollen will be transferred to another flower of its species.

In biodiverse ecosystems like the tropics, many different species of flowers and pollinators live in close proximity. Attracting many different pollinators in these environments means expending abundant energy on resources that will be mostly consumed, and the pollen picked up is unlikely to transfer to another flower of the same species. So, many tropical flowers exhibit high pollinator specificity: They target a very specific group of pollinators to enhance their reproductive success.

Dr. Jasen W. Liu at the University of California, Davis studies perfume flowers, a group of (mostly) orchids that are solely pollinated by male euglossine bees. These flowers have ingeniously harnessed a tropical bee’s mating behavior for their own reproduction through an alternative means of attraction—perfume.

Male euglossine bees collect fragrance molecules from flowers in specialized compartments on their hind legs to attract females (Figure 1). Female euglossine bees will only reproduce with males that succeed in concocting and dispersing his species’ preferred perfume composition.

Perfume flowers’ only mechanism for attracting pollinators is through the synthesis of these scent compounds. Male bees benefit from seeking out flowers that produce chemical profiles that closely match the preferences of their species. So, the closer the flower’s perfume composition is to the target bee’s specific preferences, the more likely the bee is to visit. Over time, the bees inadvertently breed flowers that smell more and more to their liking. In some extreme cases, a given perfume flower is solely pollinated by one species of male euglossine bee. This high degree of specificity drives reproductive isolation and speciation, explaining the incredible diversity we see today.

Upon luring the bee, the flower affixes pollen to the bee, often in astonishingly innovative ways. All orchids produce waxy pollen sacs called pollinia, which they stick to pollinators with a sticky pad called a viscidium. They invest a lot of energy and resources on these sacs, so the flower needs to maximize its chances that the pollinia are deposited only on their target pollinator and that they are securely attached to the pollinator. These selection pressures have resulted in incredible specialization in shape (Figure 2).

Watch perfume flower pollination in action!

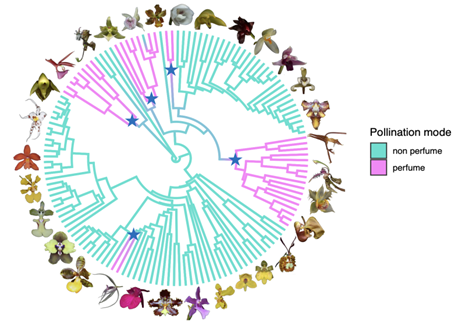

An Orchid’s Trap | Wings of Life

Over the course of his PhD, Liu has asked many questions about the evolution of these unique flowers. His work spans a combination of approaches including comprehensive shape analyses across hundreds of different perfume flowers and analysis of perfume chemical composition across species. These impressive, robust datasets integrated Liu’s collections with the work of other collaborators, and allowed for modeling the rate of shape and scent diversification of perfume flowers as compared to other orchids (Figure 3). Cumulatively, his results demonstrate that, in lineages of orchids that target male euglossine bees for pollination, the rate of morphological diversification is exceptionally fast.

Liu's work underscores how ecological interactions can facilitate rapid evolution.

The immense biodiversity of the tropics, resulting from millions of years of complex ecosystem interactions, is at risk. Flowers with high pollinator specificity are less able to adapt to change than generalist flowers that attract a variety of pollinator species. With low pollinator specificity, if some pollinators disappear, others will be left to continue pollinating. Meanwhile, flowers with more pollinator specificity are more vulnerable, as they are reliant on their specific target pollinator. Thus, understanding the mechanisms that drive and sustain high-biodiversity ecosystems is critical for informing conservation efforts.

About the author: Emma Hotchkiss is a graduate student in the Hamby Lab researching best management practices for managing corn earworm in sweet corn within an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) framework.

![[Seminar Blog] From Sweat to Supper: The Sensory Science Behind Mosquito Host Detection](/sites/default/files/styles/16_9_350x200/public/articles/seminar-blog_raji_fall25_pic-1.jpg.webp?itok=sE7-bgrW)

![[Seminar Blog] How Researchers Use Genomic Monitoring to Fight Mosquitoes Spreading Malaria](/sites/default/files/styles/16_9_350x200/public/news/anopheles%20gambiae%20mosquito.jpg.webp?itok=n2KSAE9f)

![[Seminar blog] What Do you Do with a Drunken Crayfish?](/sites/default/files/styles/16_9_350x200/public/news/crayfish.png.webp?itok=0ORC_Vvi)