Written by: Lillian Davis & Logan Lott

When we think of a mosquito, the image that comes to mind may be a small blood-sucking pest. Many people don’t realize that the term “mosquito” refers to a large group of flies (Culicidae) that have a slender body, long legs, one pair of wings, and long, slender mouthparts. Both male and female mosquitoes drink nectar. Females of several mosquito species will also consume blood prior to laying eggs, which is often referred to as a “blood meal”. Through this process of feeding, mosquitoes can act as vectors of diseases, transmitting diseases such as malaria and yellow fever to the humans they feed on. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 31,000–82,000 people die from yellow fever each year, and annually, an estimated 610,000 die from malaria.

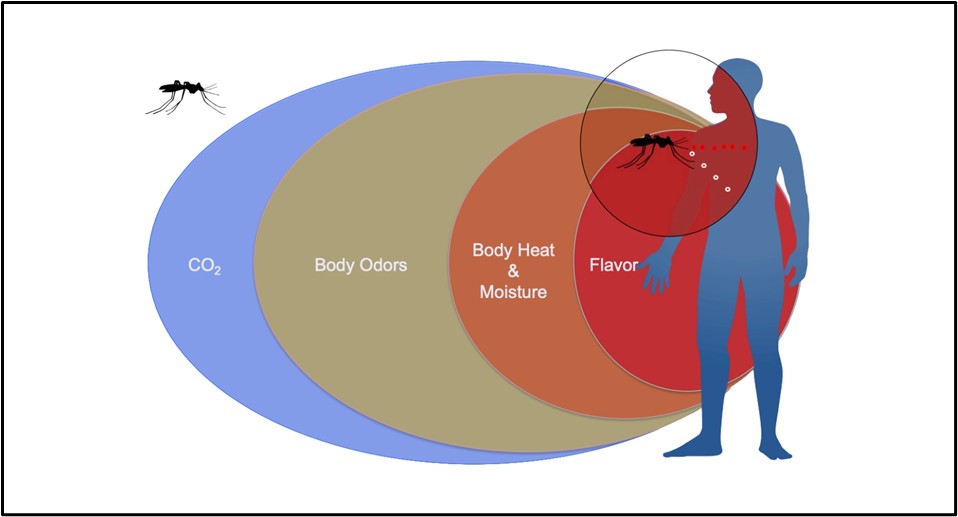

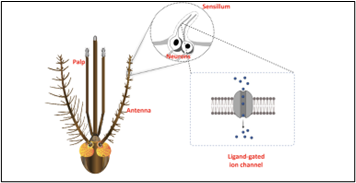

How do mosquitoes find a human host to bite? Mosquitoes pick up on some visual cues and can also detect heat emanating from us, but their dominant method of host detection likely relies on smell (Raji et al. 2019). Although they rely on carbon dioxide to locate hosts at a distance, they can then hone in on other volatiles, such as lactic acid, once they are closer. While Dr. Joshua Raji was at Florida International University, he and other researchers examined Aedes aegypti mosquitoes to determine which specific chemoreceptors located on their antennae and mouthparts play the largest role in the mosquitoes finding a host to feed on. These chemoreceptors, known as odorant receptors (ORs) and ionotropic receptors (IRs), act as gates in the cell membrane. These tiny gates, located on neurons, open when a specific smell binds to them, such as acids from human skin.

Prior to Dr. Raji’s research, odor-tuned IRs in Drosophila had already been shown to require Ir8a as a co-receptor for acid-sensing neurons (Silbering et al. 2011). IRs had also been shown to be expressed in all three smell-detecting body parts of mosquitoes, including the antennae, maxillary palps, and labellum. However, in Aedes aegypti, Ir8a is found in transcript abundance only in the antennae (Matthews et al. 2016). Building on this knowledge, Dr. Raji investigated the role of Ir8a in mosquitoes and its importance in detecting acids associated with host location (Raji et al. 2019).

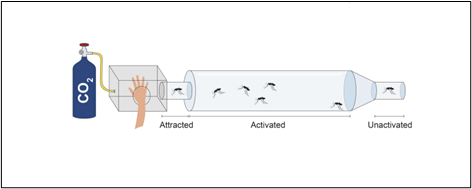

One way that researchers have been testing the role of the IR8a gene in mosquitoes is by using CRISPR, a gene-editing technology, to disable the IR8a gene in several individual Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. These mutated mosquitoes were then placed in a container on the opposite side of some mesh and exposed to human volunteers. Their response was measured to see if these mutated mosquitoes showed less interest in the human than their non-mutated counterparts. It was found that significantly less mosquitoes were attracted to the humans when the mosquito IR8a gene was broken (Raji et al. 2019). Understanding the mechanism by which mosquitoes detect humans can help researchers understand what scents the mosquitoes can smell. This understanding allows developers to create better traps and repellants, limiting the amount humans will be bitten by mosquitoes.

In January 2026, Dr. Raji will complete his postdoctoral training at John Hopkins and begin his new position as an assistant professor in the Department of Biology at Baylor University. Building upon his graduate and postdoctoral research, he will continue to research ionotropic receptors. His future work will examine the expression of mosquito (Anopheles gambiae) IRs in fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster). Dr. Raji plans to genetically modify the flies by deleting the native receptors and introducing mosquito IRs. Using the “mosquitofied” fly model, he aims to more clearly isolate and understand the function of all odor-sensing ionotropic receptors by comparing the modified flies to non-modified flies. Dr. Raji’s long-term research goal is to better understand mosquito chemoreceptors and their role in host acquisition. By understanding more about these olfactory processes, he hopes to provide information useful in improving modern vector control methods and strategies to reduce the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases.

About the authors:

Lillian Davis is a first year PhD student in the Department of Entomology and is currently rotating through research labs. She has previously researched aquatic insects and the genomics of webspinners.

Logan Lott is a first year master’s student Department of Entomology in the Megan Fritz lab. She is currently working on how tick ecology, habitat characteristics, and human behavior interact to shape the spread of tick-borne diseases in Maryland.

Raji Joshua. 2025. Sniffing the Sweat Signal: Mosquito Receptors That Smell Our Acid Trail [Powerpoint slides]. Department of Entomology, University of Maryland.

![[Seminar Blog] Perfume Flower Orchids Evolved Exceptionally Fast, Thanks to their Strange Pollinators](/sites/default/files/styles/16_9_350x200/public/articles/fall25seminar-blog_liu_fig-1_0.png.webp?itok=MtlUNt17)

![[Seminar Blog] How Researchers Use Genomic Monitoring to Fight Mosquitoes Spreading Malaria](/sites/default/files/styles/16_9_350x200/public/news/anopheles%20gambiae%20mosquito.jpg.webp?itok=n2KSAE9f)

![[Seminar blog] What Do you Do with a Drunken Crayfish?](/sites/default/files/styles/16_9_350x200/public/news/crayfish.png.webp?itok=0ORC_Vvi)