By Lasair ní Chochlain and Eva Perry Urban trees provide important habitats for insects and other arthropods. Dr. Paola Olaya-Arenas, an adjunct professor at Universidad Icesi, presented the results of her research on Bogotá’s urban trees and associated insect communities to the University of Maryland’s Department of Entomology this April. Dr. Olaya-Arenas and collaborators sampled insects associated with Ficus americana Aubl. located in parks and on sidewalks in three urban areas in Bogotá, Colombia. A diverse and abundant community of herbivores, predators, and parasitoids was sampled, and information about their feeding habits, other host trees, and damage to plant tissue is described in Dr. Olaya-Arenas et al., 2022 bilingual publication “Insects associated with urban trees in Bogotá (Colombia): exploring their diversity and function.” This publication can be downloaded from the following link (Electronic book link), and it is a good guide for citizens and visitors of the city. Dr. Sara Via's webinar series, "Climate & Biodiversity Action", has begun! Next talk, "Regenerating our soil," is Wednesday, June 19, 2024, 4-5:30 pm. Tune in to find out what healthy soil is and how we can get it back.

Can't wait till June for expert advice on climate change?! Want to do something now but not sure what? Check out webisodes on her youtube page, Sara Via: Climate Change Impacts & Solutions  Lasair (far left) at the Student Leadership Award ceremony | photo credit: Student Affairs Lasair (far left) at the Student Leadership Award ceremony | photo credit: Student Affairs Congratulations to Lasair ní Chochlain, MS Student in Dr. Hamby’s Lab, for being named one of this year’s Distinguished Services Award finalists by campus’s Division of Student Affairs. Lasair is not only a talented researcher but also a fierce disability advocate. When Lasair isn’t researching the ecological interactions that structure insect communities and sustainable IPM techniques for grain and small fruit crops, they are inviting disability advocates to talk at our Entomology speaker’s series and facilitating affinity spaces for UMD graduate students with disabilities - a space to find support, resources, and community. Please join us in applauding Lasair for this well-deserved recognition & thanking them for their dedication to this important work. Watch Lasair being acknowledged for their efforts at campus’s Student Leadership Award ceremony held this May. They are mentioned at about 2:00:03. By: Amanda Brucchieri and Helen Craig

On any given day, Dr. Tanisha Williams might be found exploring the desert in search of bush tomatoes, analyzing historical herbarium samples, or nurturing a vibrant community of Black botanists. What underscores all her work is the elevation and exploration of the relationships between people and plants, especially in the context of human mediated climate change caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gases (IPCC, 2013). In her work, Dr. Williams investigated how this change is affecting the phenology and diversity of plants, particularly in the context of climate change and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). written by: Ben Gregory and Minh Le

Vampires do exist – they’re just tiny and have six legs. Blood-feeding insects, such as mosquitoes, feed on the blood of other animals to complete their life cycle. Blood provides many essential nutrients that aren’t easy to get elsewhere in nature. Unfortunately for us, blood-feeding insects can carry pathogens that cause human diseases, like malaria, West Nile, and Zika. For this reason, many scientists are interested in learning how the process of blood feeding works, and what we might be able to do to keep ourselves safe from it. One of these scientists, Dr. Chloé Lahondère of the Department of Biochemistry at Virginia Tech, has spent years learning about one unusual element of blood-feeding that you probably haven’t considered: how to stay cool. Your blood is hot – about 100°F in your body! Given that insects are cold-blooded animals and must maintain their body temperature below a certain level, the question arises “how does a blood-feeder feed on piping hot blood without overheating? Dr. Lahondère is using the kissing bug (Figure 1, Left) to answer this question.  Samantha Rosa Samantha Rosa We are thrilled to extend a big CONGRATULATIONS to Samantha Rosa, for being selected to join the esteemed cohort of NOAA’s Margaret A. Davidson Graduate Fellows! Samantha Rosa is a graduate student in the Gruner and Espíndola Labs. As part of the fellowship Samantha will conduct collaborative research with the Heʻeia National Estuarine Research Reserve in Ka-waha-o-ka-manō on the island of O‘ahu. Her research will focus on developing K-12 Community-Driven Science curriculum and programming that draws on Indigenous and contemporary knowledge to empower children and educators to lead biocultural restoration and management of Hawai‘i's cultural and ecological systems. Samantha is excited to contribute her experience as a classroom teacher and ecologist towards enhancing the education programs at the only NOAA reserve formally recognized as an Indigenous and community-conserved area. Dr. Karen Rane has been the Director of the University of Maryland’s Plant Diagnostic Lab (PDL) since 2007. After 17 years of service and a WOW # of plant samples processed, she has decided to turn in the towel and retire this semester. We thank Karen for lending her expertise to our Departments, the University and broader community and wish her all the best in retirement. For more on Karen and her service check out the write up from her National Plant Diagnostic Network (NPDN) - Lifetime Achievement Award and recent(ish) graduate student blog about her work, "Catching bugs isn’t just for entomologists: Inside the University of Maryland’s plant diagnostic lab"

This semester the Department was saddened by the loss of Professors Emeriti Don Messersmith and Charlie Mitter. They both left an indelible mark on students, colleagues and the field of Entomology. Here we take a brief look back at their legendary careers.

Congratulations to Dr. Margaret Palmer on her election to the American Academy of Arts & Sciences! We are thrilled to see her receive this prestigious honor, sharing in President’s Pines sentiments…

“Margaret Palmer's election to the American Academy of Arts & Sciences is a richly deserved honor," said university President Darryll J. Pines. "Her unwavering commitment to both academic excellence and real-world impact is truly inspiring. The University of Maryland is incredibly fortunate to count her among our faculty.” Check out the University's full press release here>>

As the Spring semester draws to a close, we extend our THANKS to everyone for their dedication and hard work in teaching, extension, and research. This term has been filled with achievements, learning experiences, and moments of both joy and sorrow. In this newsletter, we reflect on Spring 24 and look forward to summer. Join us https://mailchi.mp/.../department-of-entomology... (MD Day volunteers | photo credit: Evans)

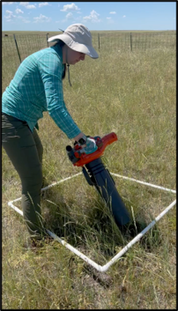

Fig. 1. Dr. Bloodworth sampling for grassland bugs Fig. 1. Dr. Bloodworth sampling for grassland bugs written by: Allison Huysman, Leo Kerner and Ben Burgunder It is a dry day in the Montana rangelands, a vast landscape of sagebrush, prairie junegrass, and purple prairie clover. Dr. Kathryn Bloodworth is vacuuming the plants. She wields a modified leaf blower designed to suck up the insects that call this wide-open space home (Fig. 1). Her goal: to understand the links between insects, grassland plant communities, and drought. Shout out to Entomology Ph.D. student Megan Ma (Shultz Lab & Wood Lab at Smithsonian NMNH) for receiving the prestigious National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship, which recognizes outstanding graduate students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

Insect Terps in Fritz Lab collaborate with NC State University on genomic approach to identify signs of emerging pesticide resistance. From AGNR press release: “Global food security and protection of public health rely on the availability of effective strategies to manage pests, but as it currently stands, the evolution of resistance across many pests of agricultural and public health importance is outpacing the rate at which we can discover new technologies to manage them,” said Megan Fritz, an associate professor of entomology at UMD and senior author of the study. “I'm really excited about this study, because we're developing the framework for use of genomic approaches to monitor and manage resistance in any system.” Check out full AGNR press release here>>

Share your colleagues exciting work on social media (X , facebook) or wherever & however you like to spread science. "Legacy effects of long-term autumn leaf litter removal slow decomposition rates and reduce soil carbon in suburban yards," out in the journal Plants, People, Planet, is one of Burghardt Labs latest pubs. Their study finds that in places where people historically have left their fallen leaves to decompose, without removing them, the soil holds up to 32% more carbon on average. Check out AGNR's press release here. Includes quotes by Max Ferlauto and suggests some ways one can adopt leaf leaving practices in the landscapes they manage.

Share your colleagues work via facebook, X or over your yard fence to a neighbor.

[Seminar Blog] Designing and managing agricultural landscapes for insect driven ecosystem services4/2/2024

Dr. Nate Hann Dr. Nate Hann written by: Brendan Randall & Angela Saenz A brisk, foggy morning; the sun rises on a midwest farm. Corn stalks sway for as far as the eye can see, seemingly the only life around. If one looks carefully, however, one will find the farm is teeming with life. Dr. Nate Haan is fascinated by the diversity of organisms on farms and how we can understand their ecology to improve farm sustainability and conservation of native biodiversity. Now an assistant professor in the Entomology Department at the University of Kentucky (UK), he is excited to answer fundamental questions about how farm management practices affect insects. In his seminar talk, Dr. Haan presented various approaches to test his central research question–does management affect insects in agricultural landscapes?  Katy Evans (Espindola Lab) has been awarded the esteemed Ann G. Wylie Dissertation Fellowship by the University of Maryland’s Graduate School! Awarded to students in the final stages of their doctorate (wow, Katy, getting close!), the Wylie Fellowship provides one semester of support during the 2024-2025 academic year. Katy's dissertation research aims to understand plant-insect interactions and their movements in rapidly changing landscapes, and consequential effects on plant reproduction. She uses experimental and observational data to investigate the effects of floral diversity on beneficial arthropods, and its repercussions on nearby plant fitness and reproductive success. Please join us in giving Katy a round of applause for this well-deserved recognition! Harriet Harris, an undergrad pursuing a minor and honors in ento w/ Dr. vanEngelsdorp, shines in Maryland Today. In addition to being an accomplished student and kick-butt roller derby player, Harriet is co-founder of BaltiSpore, a company that markets "functional" mushroom products for various health benefits.

Share Harriet's fungipreneurial spirit with your networks on facebook, X or wherever you like to excitedly holler about fun interesting things.  A picture of Dr. Medina A picture of Dr. Medina written by: Jenan El-Hifnawi and Michael Adu-Brew Academic institutions pride themselves on principled support for evidence-based solutions. This support, however, does not always seem to apply to institutional approaches to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) argues Dr. Raul Medina, a professor and member of the Diversity Science Research Cluster at Texas A&M. written by: Angela Saenz and Eva Perry

Islands have been the backdrop of considerable scientific research and advancement for centuries, and not just because they tend to double as a nice vacation spot. What makes many islands so special to science and scientists is their isolation from other land masses, limiting the movement of species to and from them. This isolation provides a rare open-air opportunity to study how evolutionary processes shape ecological communities: think Darwin’s finches and the Anolis lizards of the Caribbean, or, in Dr. Natalie Graham’s case, arthropods on the Hawaiian archipelago. Congratulations to the recipients of the Spring 24 Ernest N. Cory Undergraduate Scholarship! Seth Caban (Gruner Lab), Kyree Day (Hamby Lab), Nicole Rieger-Erwin (Burghardt Lab), Felicia Shechtman (Lamp Lab), Michail Siokis (St. Leger Lab) and Fiona Torok (Lamp Lab) have all made extraordinary efforts in Entomology. "Read more" for a bit more about the recipients.

Figure 1. Culex mosquito. Photo: Ben Burgunder Figure 1. Culex mosquito. Photo: Ben Burgunder written by: Allison Huysman, Kathleen Evans & Taís Ribeiro As entomologists, we are often asked what mosquitoes are good for. These commonly hated insects - which are especially pesty during the summer months - are actually fascinating research subjects. Mosquitoes are extremely diverse, with around 3,500 species, and are also ecologically relevant. Several species are responsible for biological control (by eating other mosquito larvae that cause diseases) and others even pollinate! Unfortunately, some species drink human blood, and some of these are vectors of deadly diseases. Studying these vectors can help improve the prediction of diseases and help to control outbreaks. Here at the University of Maryland Entomology Department, students in the Fritz lab research different ways to predict the spread of Culex mosquitoes (Figure 1) and the viruses they can spread. In their Research in Progress talks, M.Sc student Ben Burgunder and Ph.D student Ben Gregory presented their work modeling the community composition and thermal tolerance of Culex mosquitoes. written by: Megan Ma and Eric Hartel

Scientists can propose how and why species evolve by studying the shapes of anatomical structures across animals. They can investigate what morphologies may correlate with specific functions and how the interplay between an organism’s environment and its morphology can facilitate diversification. In a well-known example, Charles Darwin observed many species of finches with varying beak shapes and sizes. A correlation was found between beak morphology and diet type: insectivorous finches had long, sharp beaks to probe and capture prey, while seed-eating finches had stronger, shorter beaks to crack open seed casings. With modern tools, continued research on these finches reveals greater information on their evolution, such as how beak shape is also correlated with altered vocalizations. It has also helped explain how different species with different beak morphologies coexist in the same habitat1. These beaks are an example of how shapes evolve to accommodate the survival and fitness of an organism, and this study system is an example of how the incorporation of modern techniques allows for the comprehensive study of shape evolution. |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed