|

This publication, Spotted Wing Drosophila Monitoring and Management (FS-1023), is a series of publications of the University of Maryland Extension and the Department of Entomology. Co-authors by Kelly Hamby ([email protected]), Bryan Butler ([email protected]), Kathleen Demchak ([email protected]) and Neelendra Joshi ([email protected]) The information presented has met UME peer review standards, including internal and external technical review. For more information on this and other topics visit the University of Maryland Extension website. What impact do pesticides have on Honey bees? Honey bee health is impacted by a variety of factors (such as pests, disease, and nutritional stress) and a multitude of interactions between these factors, making the solution to our nation’s bee health problem a difficult one to find. However, when the topic of honey bee health comes up in the media, the focus is almost always on pesticides. While pesticides are most certainly an issue for honey bees, it is important to realize that real-world exposure levels must be considered when looking at how pesticides can affect bee health. Dr. Reed Johnson of Ohio State University has done just this. As the colloquium guest of the UMD Entomology graduate students, Dr. Johnson discussed results of studies performed by his team on real-world agricultural field pesticide exposures for honey bee colonies.  A pesticide kill that resulted in piles of dead bees out front of their colonies. Photo credit: http://www.centerforfoodsafety.org/issues/304/pollinators-and-pesticides/press-releases/2053/uk-parliamentary-commission-calls-for-moratorium-on-bee-killing-pesticides# A pesticide kill that resulted in piles of dead bees out front of their colonies. Photo credit: http://www.centerforfoodsafety.org/issues/304/pollinators-and-pesticides/press-releases/2053/uk-parliamentary-commission-calls-for-moratorium-on-bee-killing-pesticides# Pesticides need an EPA Risk Assessment in order to be registered and authorized for use. The risk to bees is judged through a calculated Risk Quotient. The criteria of acceptable risks have also become stricter: it is not enough anymore for a pesticide to just not kill bees, to register a product, applicants need to prove that they do not harm any pollination services, biodiversity and hive products. The new regulations made overt and massive bee kills rarer, but they still present some limitations. For one, the Risk Quotients are based on testing done on individual adult bees. But honey bees do not live as individual bees; they are part of a superorganism: the colony. Testing the impact of pesticides on whole colonies is a challenging task. One colony can contain up to 50,000 individuals in a variety of reproductive castes and life stages. With this in mind, Dr. Johnson chose to conduct an in-hive based study in an attempt to solve a problem faced by a select group of California beekeepers (Johnson & Percel 2013). Almonds are a major pollinator crop in the US. With over 800,000 acres of almonds in the Central Valley of California, and about 2 honey bee colonies required per acre, almonds pollination contracts are a major source of revenue for US beekeepers. Additionally, some beekeepers in this region of California also specialize in queen rearing. Each year over 1 million queens are produced in the region. A few years back, those queen producers started complaining that about 80% of their queens were dying after the almond bloom. Was a product used during the bloom responsible? Several pesticides, labelled “bee safe” were indeed applied while flowers were in bloom: fungicides, herbicides and a few insecticides, none of them acutely toxic to bees according to standard testing. One of them in particular, received a lot of blame from beekeepers: the fungicide Pristine. In 2012, Dr. Johnson performed a full hive study to test the effect of Pristine on queen development using field realistic levels of exposure (Johnson & Percel 2013). The colonies were given frames of pollen contaminated with different concentration of Pristine. For comparison, the experiment also provided a negative control (non-contaminated pollen, which should yield no effect on development) and a positive control (contaminated-pollen with a chemical known to impact developing bees: the Insect Growth Regulator Diflubenzeron). The positive control is an essential part of a good scientific study: if no effect can be seen in the positive control, the conclusion should be that the something in the method of application was deficient rather than that the product had no effect. Each colony in the study was used to rear queens and the survival of those queens was followed throughout their development, from egg until emergence. The results showed that the method was appropriate: the positive control was associated with a high level of kill in the queens, as expected. But the different concentration of Pristine did not seem to have an effect on queen survival: the levels were similar to the negative control. So, if Pristine was not killing the queens in CA almonds, what was? The solution to this question was found in the CA Pesticide Database. California is the only US state in which every pesticide application has to be recorded in an official database. This mine of information provides a comprehensive documentation of all pesticide applications since the 1990’s. The database revealed that a certain insecticide was regularly sprayed during bloom on almonds, to control for the Peach Twig Borer. The name of this insecticide: Diflubenzuron. Does that ring a bell? This was the Insect Growth Regulator that was used as a positive control in Johnson’s study. Dr. Johnson performed another study, with the same design, to test different concentration of Diflubenzuron and found a clear dose-response relation: at high concentrations, the product would kill all queens; at moderate concentrations, the product had a marked effect. Interestingly, that product used to be labelled “bee safe”, because when tested on workers, the product did not seem to have such an effect. Pesticide Risk Assessments should represent complete assessments of risk and the examples provided by Dr. Johnson pointed to the limitations of the current standard methods required by regulations. By focusing on individual worker adults, and ignoring the impact on the other castes (such as the queens), other life stages, and whole colony impacts, current risk quotients are under-evaluating the real risk of pesticides to beneficial insects, such as honey bees. Another limitation of standard methods is how they focus on single pesticide exposure. We know that bees are never exposed to only one product at a time: 96% of pesticide applications are performed as “tank mixes” where several products are mixed together. Despite the confusion surrounding Colony Collapse Disorder, honey bee population trends, and mortalities, one thing can be certain: beekeepers in the US are losing an unacceptable number of colonies every year. So far, beekeepers have been able to keep up with their losses by splitting colonies, but at great cost, both in labor and financially. Beekeeping is harder today than it was in the past. As a result, managed bees have become more valuable, and the level of loss that a beekeeper would deem acceptable reduced. While not the only problem for honey bees, pesticide exposure is certainly a noteworthy one. Click here to see more of Dr. Johnson’s work on the effects of pesticides on honey bees (Johnson et al., 2010). References:

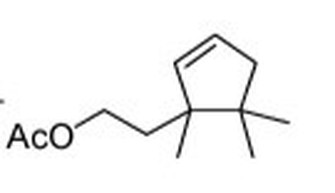

Johnson, R. M., Ellis, M. D., Mullin, C. A., & Frazier, M. (2010). Pesticides and honey bee toxicity - USA. Apidologie, 41(3), 312-331. doi:10.1051/apido/2010018 Johnson, R. M., & Percel, E. G. (2013). Effect of a Fungicide and Spray Adjuvant on Queen-Rearing Success in Honey Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Journal of Economic Entomology, 106(5), 1952-1957. doi:10.1603/ec13199 About the Authors: Nathalie Steinhauer is a PhD student working in Dennis vanEngelsdorp’s Lab. She links the risk factors associated with beekeeping management to colony mortality. Andrew Garavito is a Master’s student in Dennis vanEngelsdorp’s Lab. He is studying honey bees; with a focus on the diversity of pollen types brought in by foragers, and the health effects of different pollen diets. Meghan McConnell is a Master’s student in Dennis vanEngelsdorp’s Lab. She is studying mechanical methods of control for the honey bee parasite Varroa destructor.  The Terp and Eagle Science Club (TESC) is a STEM tutoring program for local elementary school students. Carole Highlands Elementary School (Eagles) is a nearby Title I school where most of the parents have not attended even high school and 99% of the students receive free lunch and breakfast. TESC aims to promote an interest in the sciences and engage students in both core and abstract learning inside and outside the classroom. With leadership from Dr. Marcia Shofner, our BSCI students began a tutoring program for 4th, 5th and 6th grade students in STEM homework three times a week last spring to help motivate these kids to come to college. This fall, the attendance doubled! In order to continue, our BSCI tutors need your support for transportation and background checks, school supplies, snacks and STEM enrichment material for the 58 kids who regularly attend. ******Please give your support to this BSCI Launch via this site******* More are signing up each week and any donation amount - $1 to $1000 - will help! Thank you for supporting this important effort. Sexy-smelling compounds provide a promising tool for mealybug management Mealybugs (family Pseudococcidae) are small insect pests commonly an issue in greenhouses and nurseries, especially in warmer climates. Dr. Rebeccah Waterworth, a postdoc in the University of Maryland’s entomology department, did her dissertation work while at the University of California Riverside on mealybugs in a Californian production nursery setting. Mealybugs are among the least apparent of pests. They are small insects and are only easy to see once they have accumulated in large numbers (Figure 1). On top of that, current monitoring methods for mealybugs often involve destructive sampling of plant material, which is problematic if a nursery is trying to produce blemish-free plants. If one could detect them earlier, more options would be available to get rid of them before they start damaging the plants. Figure1: Accumulation of obscure mealybugs. Photo credit Rebeccah Waterworth. Sex pheromones have been successful in other cropping systems (e.g. as a mating disruption method in moths in cranberry, Deutsch et al. 2014); however using sex pheromones as a monitoring technique of mealybugs is relatively recent. The chemistry is ready: sex pheromones of some species of mealybugs have already been isolated in a laboratory setting. By placing sticky traps with a lure saturated in the female sex pheromone out in the field, one can collect the male mealybugs (Figure 2) attracted to the pheromone. The presence of male mealybugs implies that there is in fact a mealybug population present. But could those traps be used to detect, monitor and estimate mealybug population size in a nursery? Figure 2: A mealybug pheromone trap. Photo credit Rebeccah Waterworth. Rebeccah set out to answer these questions in ornamental nurseries in California (Waterworth et al. 2011a). By placing sticky traps out in the field with lures of different pheromone doses she found that the male mealybugs are sensitive to very low doses of female sex pheromone. This is good news, because the mealybug pheromone chemicals (Figure 3) are complex molecules that are difficult and expensive to make in a laboratory setting, so the less one needs, the better. Additionally, she used the pheromone traps to estimate mealybug abundance. First, traps were set out, mealybug males were collected and counted and then compared to the true density of mealybugs found in plant samples. This resulted in a mathematical relationship that can be used to estimate true mealybug abundances in the field. Pheromone based sticky traps can now be utilized by growers to monitor mealybug populations. Figure 3: Structure of the longtailed mealybug mating pheromone. Another potential use for pheromones comes in the form of mating disruption. If enough pheromones are released at once, the male insects become inundated with signals and are unable to follow the trail left by an actual female. Without this path to the female, no mating occurs. Rebecca wanted to determine if mating disruption was a feasible tool for combating mealybugs. In testing this feasibility, Rebeccah learned some interesting aspects of mealybug biology (Waterworth et al. 2011b). First, the three species of female mealybugs she studied are not parthenogenetic, so they have to mate with a male to produce offspring. This was good news: if pheromones could prevent the males from getting to the females, there would be no future generations of mealybugs. Second, female mealybugs live for a very long time for an insect. The longtailed mealybug female, for example, lived up to 137 days in lab trials. Unfortunately this news was less welcome. Because of their long lifespans, pheromone clouds would need to be running continuously in nurseries for over 3 months to keep the males at bay. Although possible, keeping a control system running for that length of time would require a large quantity of synthetic pheromone. Currently, pheromone synthesis is such a complex process that only 5g of pheromone can be produced at a time, which increases costs. Rebeccah’s message was that if this process is simplified in the future, mating disruption could become a feasible control method. In all, Rebeccah’s talk showcased not only the potential uses of pheromone trapping and mating disruption in a new pest system, but also the long process that is necessary for the development of these tools. Future practical applications of these mating pheromones could not be assessed without the comprehensive understanding of mealybug reproductive biology she gained through her research. References:

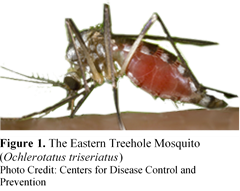

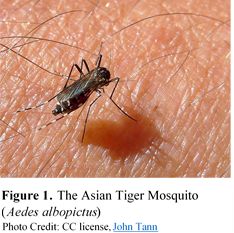

Deutsch, A., A. Mafra-Neto, J. Sojka, T. Dittl, J. Zalapa, and S. Steffan. 2014. Pheromone-based mating disruption in Wisconsin cranberries. Wisconsin State Cranberry Growers Association. Waterworth, R. A., R. A. Redak, and J. G. Millar. 2011a. Pheromone-baited traps for assessment of seasonal activity and population densities of mealybug species (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) in nurseries producing ornamental plants. J. Econ. Entomol. 104: 555-565. Waterworth, R. A. I. M. Wright, and J. G. Millar. 2011b. Reproductive Biology of Three Cosmopolitan Mealybug (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) Species, Pseudococcus longispinus, Pseudococcus viburni, and Planococcus ficus. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 104: 249-260. About the Authors: Olivia Bernauer is a first year Master’s student in Dennis vanEngelsdorp’s bee lab working with wild, native bees. Olivia is currently working with volunteers to monitor the diversity and floral preference of Maryland’s native bees. Becca Wilson is a third year PhD student in Bill Lamp’s lab. She is studying the distribution patterns and societal impact of nuisance black flies in western Maryland. Invasive Mosquito Can’t be Blamed for Spread of La Crosse Encephalitis La Crosse encephalitis is a rarely seen viral disease spread by infected mosquitoes. Typical infections present with flu-like symptoms lasting 2-3 days. Rarely, infections can lead to swelling in the brain (encephalitis) which can lead to seizures, brain damage, and, in extreme cases (<1%), death. Around the same time that LACV was invading Appalachia another pest was spreading throughout the region, the Asian Tiger Mosquito (Aedes albopictus). Notable for its love of human blood, voracious appetite, and habit of feeding all day long, A. albopictus also transmits several dangerous viruses, including LACV. Could A. albopictus be responsible for the rise in LACV infections in the Appalachia?  Historically, infections of the La Crosse virus (LACV) have been confined to the Midwestern United States, but since 2003 there has been a steady unexplained rise in the number of infections reported from the Southeastern United States (Appalachia). The mosquito that transmits the virus, the Eastern Treehole Mosquito (Ochlerotatus triseriatus), was already present in Appalachia, so the recent spread of the disease couldn’t be blamed on an expansion of the host’s range; another culprit had to be responsible.  Doctor Sharon Bewick at the University of Maryland was part of a team that built a set of models to try and answer this question. Using research from 45 different academic publications they built models that factored in the survival and ability to transmit disease of the two mosquito species. They were then able to predict what transmission would look like in ecosystems with the native mosquito alone, the invasive alone, and with both species coexisting. Dr. Bewick predicted if LACV would spread or go extinct in the different models. While the majority of model runs with O. triseriatus indicated that the disease would spread, A. albopictus alone could not spread the disease, and in combination with O. triseriatus, the spread of LACV was lessened. The original models did not account for seasonal changes in transmission and infection, such as overwintering of mosquitoes and a large decrease in the amount of host immunity in the following year. Further model development incorporated these dynamics, and the results still indicated that disease persistence would decrease with the presence of A. albopictus under inclusion of these more realistic parameters. Why then might LACV decrease with A. albopictus presence? The models indicated that a higher biting rate, higher adult survival, and higher larval carrying capacity are the most important factors in promoting the spread of LACV in individual species models. In the model with both species, however, a slower growth rate and lower larval carrying capacity of A. albopictus along with a decrease in competitive pressure from A. albopictus on the native species led to higher persistence of the disease. This indicated that larval competition may strongly influence the outcome of the model dynamics. Aedes albopictus bite more indiscriminately and bite more humans. A. albopictus is thus less likely to pick up the virus from an infected blood meal as the meals are less likely to be from hosts that can amplify LACV. Additionally, competition between the two species’ larvae can alter the carrying capacities and survival of the native species. Consequently, competitive displacement of the native species, which does bite primarily on LACV amplifying hosts, by the invasive species, which does not, can cause a decrease in LACV spread. However, Dr. Bewick’s models made assumptions about larval competition between the species based upon direct lab competition experiments. The two species do not always overlap in time and space. For example, A. albopictus is likely to be found in urban settings, while O. triseriatus is more likely to be found in the woods. Additionally, the period of time when larvae are developing does not always overlap. Therefore, the larvae of these two mosquitoes may not be directly competing in the way the models predict, which may lead to misleading predictions about the disease’s spread. Who or what is responsible for the increase in LACV? While it appears that the A. albopictus may not be the culprit, there is another invasive mosquito which may be responsible for the spread and that deserves further investigation. The Asian Bush Mosquito (Aedes japonicus japonicus) is less-well studied than the A. albopictus and is also a newer invader that appeared at about the right time to coincide with the spread of LACV, and it is also a competent vector. Future research will involve investigating whether the Asian Bush Mosquito may be the mosquito responsible for the increased spread of LACV. References: Leisnham, P.T. & S.A. Juliano. 2012. Impacts of climate, land use, and biological invasion on the ecology of immature Aedes mosquitoes: Implications for La Crosse Emergence. EcoHealth 9:217-228. doi: 10.1007/s10393-012-0773-7 http://www.cdc.gov/lac/tech/symptoms.html About the Authors:

Peter Coffey is a Master's student whose research focuses on using cover crops to optimize sustainable farming economics. His current projects using lima beans and eggplant as model systems focus on plant nutrition, weed suppression, influences on pest and beneficial insects, and crop yield value. Follow him on twitter at @petercoffey. Becca Eckert is a Ph.D. student whose research focuses on how algae growing on leaves in headwater streams affect macroinvertebrate performance (e.g., growth) and biodiversity within leaf packs. |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed