Before you bug out for the semester, take a moment to look back at Fall 2021 with us! The Department of Entomology newsletter highlights publications, awards, defenses, media mentions and much more: https://mailchi.mp/eb2ecf9c3eb2/department-of-entomology-newsletter-fall-2021 ^Eckert RA, Lamp WO and Marbach-Ad G. Jigsaw dissection activity enhances student ability to relate morphology and ecology in aquatic insects. Journal of Biological Education. 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2021.2006268

^Evans K, Underwood RM and López-Uribe MM. Combined effects of oxalic acid sublimation and brood breaks on Varroa mite ( Varroa destructor ) and deformed wing virus levels in newly established honey bee ( Apis mellifera ) colonies. Journal of Apicultural Research. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2021.1985260 Satler JD, Carsten BC, Garrick RC and Espíndola A. The Phylogeographic Shortfall in Hexapods: A Lot of Leg Work Remaining. Insect Systematics and Diversity. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/isd/ixab015 Tait G, Mermer S, Stockton D [and 46 others including Hamby KA and ^Schöneberg T]. Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae): A Decade of Research Towards a Sustainable Integrated Pest Management Program. Journal of Economic Entomology. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toab158 Marsden BW, Ngeve MN, Engelhardt KAM and Neel MC. Assessing the Potential to Extrapolate Genetic-Based Restoration Strategies Between Ecologically Similar but Geographically Separate Locations of the Foundation Species Vallisneria americana Michx. Estuaries and Coasts. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-021-01031-z *Graham PL, ^Fischer MD, Giri A, and Pick L. The fushi tarazu zebra element is not required for Drosophila viability or fertility. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkab300 Kard BM, OI FM, Thorne BL, Forschler BT and Jones SC. Performance Standards and Acceptable Test Conditions for Preventive Termiticide and Insecticide Treatments, Termite Baiting Systems, and Physical Barriers for New Structures or Buildings Under Construction (Pre-Construction; During Construction; Post-Construction). Florida Entomologist. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1653/024.104.0308 Hensel MJS, Silliman B., van de Koppel J, Hensel E, ^Sharp SJ, Crotty SM and Byrnes JEK. A large invasive consumer reduces coastal ecosystem resilience by disabling positive species interactions. Nature Communications. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26504-4 Bold ENTM Faculty; ^ENTM current/former graduate student or post-doc; *ENTM research staff How can we keep native bee species alive?

Dr. Nathalie Steinhauer, UMD postdoc and Bee Informed Partnership science coordinator says to Capital News Service MD: Support companies working to reduce the environmental impacts affecting bee populations. & how in the world did bees survive for weeks under volcano ash following the Canary Islands eruption? Nathalie tells the New York Times: That behavior is typical of honeybees, who use propolis, which they produce from substances they collect from plants and buds, to plug tiny gaps in the hive to protect it from rainwater and drafts, said Nathalie Steinhauer, a researcher in the department of entomology at the University of Maryland Still, the fact that the bees on the island managed to spend weeks inside the hive insulating themselves from such oppressive conditions was surprising — and even inspirational, Dr. Steinhauer said. “It is a very empowering story,” she said. “It tells a lot about the resilience of honeybees. [Seminar Blog] I declare a plant-insect war: The arms-race and profiteering of species interactions.12/16/2021

We may think of herbivores, or animals that feed on plants, as large lumbering creatures grazing on grass, but most of them are, in fact, insects (Forister et al., 2015). Herbivorous insects interact with the predators that seek to eat them and the plants they rely on for food. But from a plant’s perspective, the insect herbivores are the predators. Plants rely on various tools to reduce the onslaught of attack from these foliage feeders. For example, they can utilize sticky appendages called trichomes, and deploy stinky or toxic chemicals. These interactions that originate from the plant and have impacts on herbivores are known as ‘bottom-up effects’ (Figure 1). Due to the abundance of insect herbivores in nature, they are also important food sources for insect predators and parasitoids. These interactions, which involve herbivore predators, are an example of ‘top-down effects’ (Figure 1).

In 2017, Professor Sara Via started a collaboration with the Maryland Department of Agriculture on soil health and how farmers can manage their land to store carbon in agricultural soils. As part of this collaboration and her role as one of Maryland's representatives to the Natural and Working Lands Workgroup of the US Climate Alliance, Dr. Via began a review of the scientific literature on the topic to evaluate the carbon-sequestering effectiveness of a set of 23 practices, including reduced tillage and the use of cover crops. This review led to a comprehensive report that demonstrates how increased adoption of these key practices can make agriculture a significant part of the American climate solution. The report, titled “Increasing Soil Health and Sequestering Carbon in Agricultural Soils: A Natural Climate Solution” highlights a set of farming practices that improve soil health, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and store carbon in the soil while providing economic benefits for farmers and environmental benefits for all. The table of expected GHG reductions from using each of the recommended practices was integrated into Maryland's 2030 Greenhouse Gas Reduction Act Plan as Appendix K. For more information and to download the report, check out publisher Izaak Walton League of America’s press release here>>.

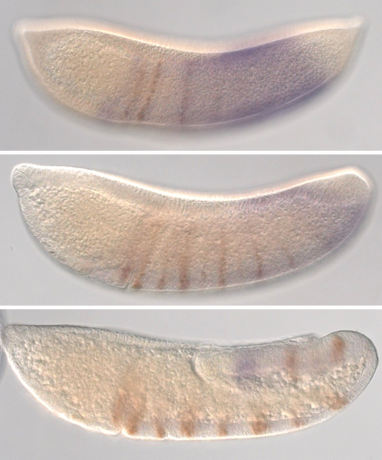

PICK LAB OBSERVATIONS OFFER CLUES INTO UNDERSTANDING HOW DIFFERENT MODES OF SEGMENTATION EVOLVE12/15/2021

Image caption- In the mosquito Anopheles stephensi, expression of segment marker gene Engrailed (brown) is activated in a wake of a wave of opa (purple) expression, which times segment specification during Drosophila development. Image caption- In the mosquito Anopheles stephensi, expression of segment marker gene Engrailed (brown) is activated in a wake of a wave of opa (purple) expression, which times segment specification during Drosophila development. Arthropods are famous for their segmented body plans, which contribute to their vast diversity through modular addition of appendages, wings and more. Segments are patterned early in embryonic development, and this process has been intensively studied in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. Drosophila is a premier model system, owing to ease and speed of culture and abundant genomic and molecular tools. However, it’s segmentation process is seemingly unlike that of most arthropods. Drosophila establishes all its segments at the same time, whereas other species specify segments one at a time over a long growth period. It has long been assumed that distantly related flies, such as mosquitoes, make this segments the same way that Drosophila do. However, while exploring the loss of an important segmentation gene from mosquito genomes, the Pick lab noticed that mosquito segmentation appeared to represent an intermediate, blending aspects of simultaneous and sequential segmentation. In their new work, published in JEZ-B, Alys Cheatle Jarvela, Catherine Trelstad, and Leslie Pick characterize this intermediate segmentation mode in the mosquito, Anopheles stephensi, and show that it is likely controlled by a progressive wave of developmental regulatory gene expression. These observations offer clues into understanding how different modes of segmentation evolve and have opened new lines of research into segment patterning in the Pick lab.

Karen Rane, director of the Plant Diagnostic Laboratory at the University of Maryland, quoted in Washington Post article on the decline of oaks in the DMV.

“The anaerobic conditions of flooded soil are not good for oaks,” said Rane, noting that many of the hard-hit oaks are next to highway construction, where there are changes in drainage and soil compaction. “They lose oxygen in the soil. That’s stress on older trees — or on any tree, but older ones can’t tolerate it the way younger trees can. That may have triggered an acceleration of decline in these older trees,” Rane said. “Once the trees weaken, trees emit signals that allow opportunistic insects to find them and attack. That’s the last straw that breaks the camel’s back.” Read full article here>> In spring of 2018 the Fritz Lab was asked to investigate a mosquito infestation on federal property in Southwest Washington, DC. So PhD student Arielle Arsenault-Benoit and Assistant Professor Megan Fritz headed off to the capital to scrounge around in dirty basements and look for mosquitoes. Could moderation of winter conditions make belowground urban structures a refugia for warmer-climate species, like Ae. aegypti and Cx. quinquefasciatus, allowing them to overcome assumed thermal barriers? To test their hypothesis they surveyed belowground levels of nearby parking structures for mosquitoes and standing water in the summer months of 2018 and 2019 and compared winter and spring temperatures above and belowground. Their findings, published in the Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association, found several species using these structures as adults, but only a few species (and ones that can transmit disease) use them as breeding and development sties. Belowground urban infrastructure may allow populations to persist for longer and build up earlier in the spring, plus warmer temperatures can shorten the development and generational time, extending the breeding season, increasing population size, and potentially affecting disease transmission. Given these results, the authors suggest pest control operators and local public health officials incorporate surveillance of these structures into their integrated pest management programs. This article also includes new records of Aedes aegypti populations beyond the Capitol Hill neighborhood in Washington DC.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed