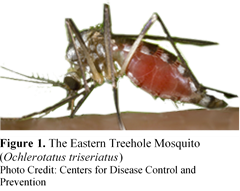

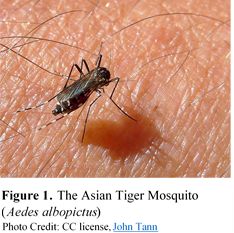

Invasive Mosquito Can’t be Blamed for Spread of La Crosse Encephalitis La Crosse encephalitis is a rarely seen viral disease spread by infected mosquitoes. Typical infections present with flu-like symptoms lasting 2-3 days. Rarely, infections can lead to swelling in the brain (encephalitis) which can lead to seizures, brain damage, and, in extreme cases (<1%), death. Around the same time that LACV was invading Appalachia another pest was spreading throughout the region, the Asian Tiger Mosquito (Aedes albopictus). Notable for its love of human blood, voracious appetite, and habit of feeding all day long, A. albopictus also transmits several dangerous viruses, including LACV. Could A. albopictus be responsible for the rise in LACV infections in the Appalachia?  Historically, infections of the La Crosse virus (LACV) have been confined to the Midwestern United States, but since 2003 there has been a steady unexplained rise in the number of infections reported from the Southeastern United States (Appalachia). The mosquito that transmits the virus, the Eastern Treehole Mosquito (Ochlerotatus triseriatus), was already present in Appalachia, so the recent spread of the disease couldn’t be blamed on an expansion of the host’s range; another culprit had to be responsible.  Doctor Sharon Bewick at the University of Maryland was part of a team that built a set of models to try and answer this question. Using research from 45 different academic publications they built models that factored in the survival and ability to transmit disease of the two mosquito species. They were then able to predict what transmission would look like in ecosystems with the native mosquito alone, the invasive alone, and with both species coexisting. Dr. Bewick predicted if LACV would spread or go extinct in the different models. While the majority of model runs with O. triseriatus indicated that the disease would spread, A. albopictus alone could not spread the disease, and in combination with O. triseriatus, the spread of LACV was lessened. The original models did not account for seasonal changes in transmission and infection, such as overwintering of mosquitoes and a large decrease in the amount of host immunity in the following year. Further model development incorporated these dynamics, and the results still indicated that disease persistence would decrease with the presence of A. albopictus under inclusion of these more realistic parameters. Why then might LACV decrease with A. albopictus presence? The models indicated that a higher biting rate, higher adult survival, and higher larval carrying capacity are the most important factors in promoting the spread of LACV in individual species models. In the model with both species, however, a slower growth rate and lower larval carrying capacity of A. albopictus along with a decrease in competitive pressure from A. albopictus on the native species led to higher persistence of the disease. This indicated that larval competition may strongly influence the outcome of the model dynamics. Aedes albopictus bite more indiscriminately and bite more humans. A. albopictus is thus less likely to pick up the virus from an infected blood meal as the meals are less likely to be from hosts that can amplify LACV. Additionally, competition between the two species’ larvae can alter the carrying capacities and survival of the native species. Consequently, competitive displacement of the native species, which does bite primarily on LACV amplifying hosts, by the invasive species, which does not, can cause a decrease in LACV spread. However, Dr. Bewick’s models made assumptions about larval competition between the species based upon direct lab competition experiments. The two species do not always overlap in time and space. For example, A. albopictus is likely to be found in urban settings, while O. triseriatus is more likely to be found in the woods. Additionally, the period of time when larvae are developing does not always overlap. Therefore, the larvae of these two mosquitoes may not be directly competing in the way the models predict, which may lead to misleading predictions about the disease’s spread. Who or what is responsible for the increase in LACV? While it appears that the A. albopictus may not be the culprit, there is another invasive mosquito which may be responsible for the spread and that deserves further investigation. The Asian Bush Mosquito (Aedes japonicus japonicus) is less-well studied than the A. albopictus and is also a newer invader that appeared at about the right time to coincide with the spread of LACV, and it is also a competent vector. Future research will involve investigating whether the Asian Bush Mosquito may be the mosquito responsible for the increased spread of LACV. References: Leisnham, P.T. & S.A. Juliano. 2012. Impacts of climate, land use, and biological invasion on the ecology of immature Aedes mosquitoes: Implications for La Crosse Emergence. EcoHealth 9:217-228. doi: 10.1007/s10393-012-0773-7 http://www.cdc.gov/lac/tech/symptoms.html About the Authors:

Peter Coffey is a Master's student whose research focuses on using cover crops to optimize sustainable farming economics. His current projects using lima beans and eggplant as model systems focus on plant nutrition, weed suppression, influences on pest and beneficial insects, and crop yield value. Follow him on twitter at @petercoffey. Becca Eckert is a Ph.D. student whose research focuses on how algae growing on leaves in headwater streams affect macroinvertebrate performance (e.g., growth) and biodiversity within leaf packs. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed