Catching bugs isn’t just for entomologists: Inside the University of Maryland’s plant diagnostic lab3/23/2020

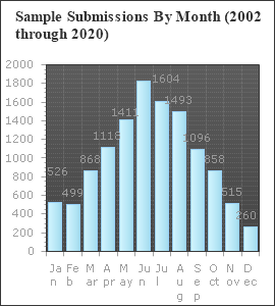

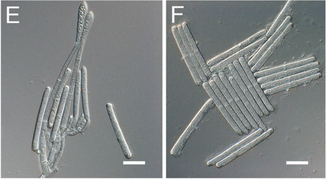

Fig. 1. Number of samples received by the UMD Plant Diagnostic Lab between 2002 and 2020. Graph kindly provided by Dr. Rane. Fig. 1. Number of samples received by the UMD Plant Diagnostic Lab between 2002 and 2020. Graph kindly provided by Dr. Rane. written by: Dongxu Chen, PhD student, Hawthorne lab and Katie Reding, PhD student, Pick lab Every gardener, farmer, or landscaper will at some point find some mysterious spots on their prized plants, or perhaps find that a random subset of their crop has wilted overnight. To anyone who’s not an expert, the pathogens causing these diseases can be hard to identify and seemingly impossible to control. Indeed, it can take much more than a trained eye to properly diagnose many plant diseases; often, axenic culture (growing only the organism of interest without contaminants) of the pathogen is required, and in some cases molecular tests are warranted. Dr. Karen Rane, the entomology department’s resident plant pathologist and this week’s colloquium speaker, uses all of these tools and more to handle the roughly 700-900 diseased plant samples her plant diagnostic lab receives each year (Fig. 1)*.  Fig. 2. Sporangia of impatiens downy mildew. Image kindly provided by Dr. Rane. Fig. 2. Sporangia of impatiens downy mildew. Image kindly provided by Dr. Rane. As Dr. Rane describes it, diagnosis is an investigative art. First, you must know how the plant under examination usually presents. Is it normal for pumpkins to be covered in lots of wart-like growths? If you’re growing knucklehead pumpkins - a cultivar specifically selected for its unique appearance - then yes, but if you’re growing sugar pie pumpkins, you might have a problem. Second, you need to know about the common problems that can affect that particular plant. If you’re witnessing classic symptoms of a well-characterized disease, further tests would be unnecessary. Next, Dr. Rane looks for patterns. A random assortment of plants showing the same symptoms is more characteristic of a disease spreading through the population, while a uniform pattern of symptoms is often seen when the underlying cause is abiotic (not biological), like damage due to an herbicide. As she’s rarely on site to inspect plants where they’re grown, she relies on her clients to provide all the contextual details of the plant’s origin and treatment. For best results, samples should be representative of the diseased population, should be submitted with root ball and surrounding soil intact, and should be accompanied by a history of any treatments applied. After this initial triage, several routine lab tests can be performed to try to diagnose the causal agent of the disease. In the lab, the first step is generally to get a closer look under the microscope. If the pathogen cannot be identified at its present state, it may need to be cultured (grown in a controlled laboratory environment). For many fungal pathogens, for instance, the morphological features present during sporulation (production of spores during reproduction of fungi) are often important for identification (Fig. 2, Su et al. 2012). If a pathogen cannot be definitively identified morphologically, diagnosticians will turn to the DNA. DNA barcoding¾using the DNA sequence usually of some housekeeping gene to determine the species of an organism¾can be very sensitive, but also more time-consuming and costly than a morphological analysis.  Fig. 3. Conidia (spores) of the fungal pathogen Calonectria pseudonaviculata found to be responsible for Sarcococca blight. Image from Malapi-Wight et al. (2016) Fig. 3. Conidia (spores) of the fungal pathogen Calonectria pseudonaviculata found to be responsible for Sarcococca blight. Image from Malapi-Wight et al. (2016) These tests can be complicated by the presence of secondary infections by opportunistic pathogens that happen upon an already compromised host. If more than one pathogen is found, how do you know which one (or possibly both) are responsible for the disease? Furthermore, if the initial identification implicates a pathogen not known to infect the host species or appears completely novel in the region, Dr. Rane does experiments to see if the pathogen can fulfill Koch’s postulates, a series of diagnostic criteria that must be met to establish a cause and effect relationship between a given pathogen and the symptoms observed. First, the suspected pathogen must be isolated from the host experiencing the symptoms and grown by itself (with no contaminants). Then, this axenic culture is used to infect a healthy, untreated individual of the same plant species the candidate pathogen was isolated from. The host is monitored to see if the first plant’s symptoms are replicated in this second plant. Then the suspected pathogen should again be isolated from this second plant and identified. For instance, when the fungal pathogen Calonectria pseudonaviculata was first found infecting Sarcococca hookeriana (an evergreen commonly called ‘sweetbox’), suspensions of C. pseudonaviculata spores were sprayed onto healthy sweetbox plants and a control group was sprayed with only water (Fig. 3). A week after inoculation, dark spots developed on the leaves, symptoms of the original infected sweetbox, and C. pseudonaviculata was reisolated from these plants, confirming it as the causal pathogen of disease. Dr. Rane collaborated with other researchers on a project sequencing the genome of this pathogen (Malapi-Wight et al. 2016). Apart from this, how much time should be spent on each case is an important factor to consider. There is a trade-off between quick but rough diagnostic methods and accurate but time-consuming ones. Often several laboratory tests are used together to validate a diagnosis. As head of a diagnostic lab servicing all of Maryland and much of the Mid-Atlantic region, Dr. Rane is often at the forefront of changes in the industry or novel exposures to pathogens. For example, due to new rules regarding the cultivation of hemp in Maryland, she received hemp samples for the first time in 2019, and diagnosed several diseases that were new reports for Maryland. Another example is the first detection of thousand cankers disease of walnut, an insect/fungus complex that wasn’t found in Maryland until October 2014. Sometimes weird, or in other words, interesting, questions make a diagnostician’s life more colorful. For example, an unidentified “tooth-like” object was received from a “victim” who claimed that he found a tooth in the dining hall food. By virtue of the practitioner's experience, Dr. Rane realized it was likely the stem of a garlic bulb. *Please note that Dr. Rane’s lab does not accept samples from home gardeners. If you are a home gardener seeking advice about a plant disease, the University of Maryland Extension’s Home and Garden Information Center would be happy to assist you. References 1. Malapi-Wight M, Saldago-Salazar C, Demers J, Clement D, Rane K, & Crouch J. (2016) Sarcococca Blight: Use of Whole-Genome Sequencing for fungal plant disease diagnosis. Plant Dis, 100(6). doi: 10.1094/PDIS-10-15-1159-RE 2. Su Y, Qi Y, & Cai L. (2012) Induction of sporulation in plant pathogenic fungi. Mycology, 3(3). Dongxu Chen is a Ph.D. student in the Hawthorne lab, investigating the genetic architecture of insecticide resistance of Colorado Potato Beetle. Katie Reding is a PhD student in the Pick lab at the University of Maryland, studying the regulatory interactions underlying segmentation of the milkweed bug embryo. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed