|

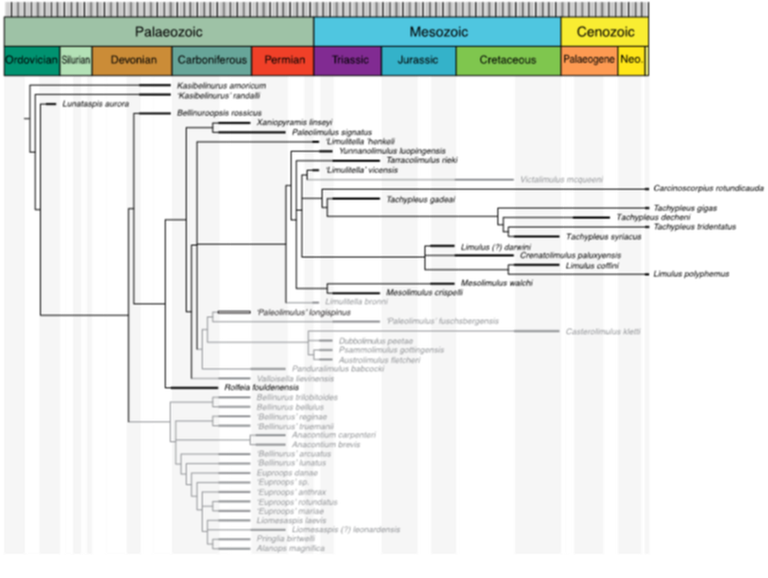

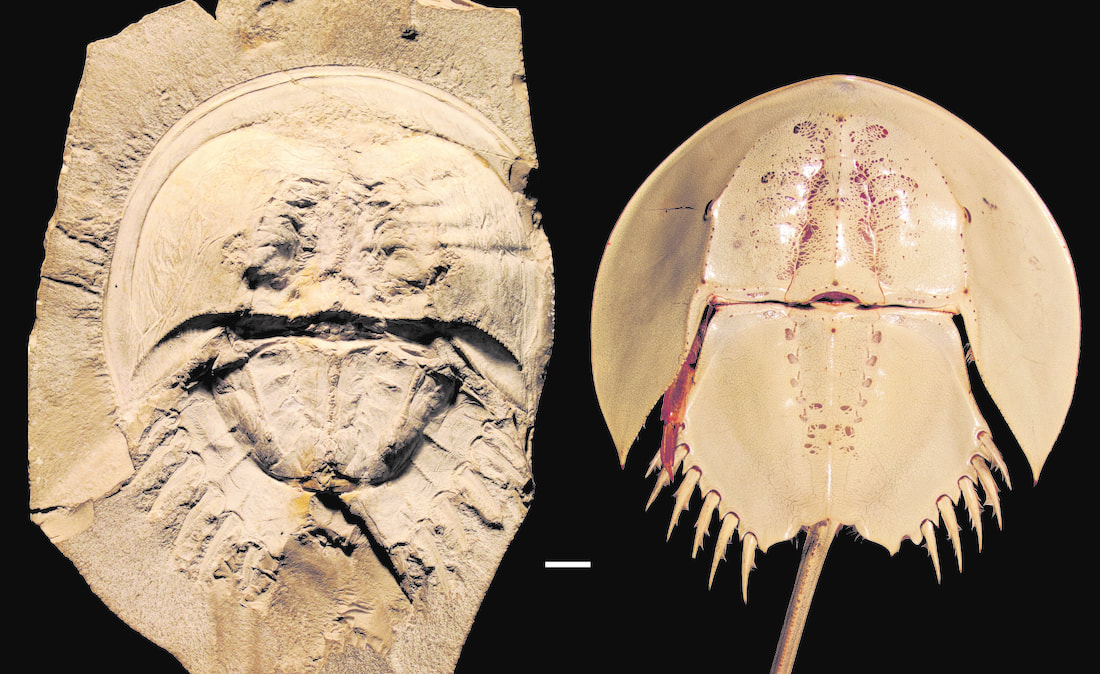

Horseshoe crabs (Order: Xiphonsura) were once thought to be a relatively static, unchanging group of organisms. Dr. Lamsdell of the University of West Virginia, however, fundamentally changed the way we view horseshoe crabs through his paleotonoligcal research on their dynamic evolutionary history.  Dr. James Lamsdell, Paleobiologist at West Virginia University, righting an upturned horseshoe crab. Dr. James Lamsdell, Paleobiologist at West Virginia University, righting an upturned horseshoe crab. If you’ve ever taken a stroll along the beaches of the Atlantic Ocean, you most likely spotted a horseshoe crab or two washing up on shore. To the untrained eye, horseshoe crabs may look no different than those fossilized 450 million years ago. During his UMD Entomology Colloquium, Dr. James Lamsdell of West Virginia University described how horseshoe crab fossils look through the eyes of a paleobiologist (a scientist that studies “old biology”). When Dr. Lamsdell walks along the Atlantic beaches, he sees a dynamic order of arthropods (Xiphonsura) more than capable of changing through time. Today, horseshoe crabs spend the majority of their lives in salty ocean water. They can only tolerate less-salty (or brackish) water very briefly as adults to spawn and when developing as larvae or juveniles. Larvae spend all of their time on brackish shores, and juveniles tend to stick close to shores too. Adult horseshoe crabs, however, are considered a saltwater arthropod. The modern-day saltwater lifestyle of adult horseshoe crabs was a longtime mystery to paleobiologists, who found numerous horseshoe crab fossils in historically freshwater environments. In the past, these scientists offed a few explanations for this phenomenon: perhaps horseshoe crabs rarely moved into inhospitable habitats or maybe horseshoe crab fossils were discovered in areas that were never actually freshwater environments. These explanations, however, fell apart as more and more horseshoe crab fossils were found alongside known freshwater organisms. Could freshwater horseshoe crabs have ever really existed? Dr. Lamsdell decided to brush the proverbial dust off of this mystery by looking at the morphospace of horseshoe crab fossils, as well as living horseshoe crabs. Morphospace is a representation of all of the characteristics (or shapes) of different horseshoe crabs. By grouping different horseshoe crabs according to defined characteristics, Dr. Lamsdell found horseshoe crabs colonized freshwater habitats on four separate occasions throughout evolutionary history. Most notably, freshwater horseshoe crabs formed distinct two evolutionary groups following the smallest mass extinction (we know of five mass extinctions events, and we’re working on our sixth).  This little mass extinction, during the Devonian period, caused sea levels to rise, which lowered the number of shallow shore environments. Shallow nearshore, at the time, was in high demand by numerous organisms. These shores became very well connected, full of prey that some horseshoe crab species couldn’t pass up. In order to take advantage of this new habitat, some horseshoe crab species evolved to retain juvenile characteristics that made navigating freshwater environments easier. Paleobiologists refer to the retention of juvenile traits as ‘paedomorphism.’ Paedomorphism is an old trick in nature: it is why we look more like baby chimps than adult chimps, and why domestic dogs look and act more like wolf pups than adult wolves. Paedomorphism can result in some major changes in appearance and biology, and for these now-fossilized horseshoe crabs, the ability to live in freshwater was one of them. The adults of these species underwent paedomorphogenesis to allow them to survive much better in freshwater, just like juvenile horseshoe crabs can today. Through careful examination of these fossils, Dr. Lamsdell found evidence of paedomorphism: young horseshoe crabs have spikes above their eyes, which these freshwater horseshoe crabs maintained into adulthood. Retention of these spikes points to the fact that these horseshoe crabs may have also retained the ability to survive in freshwater habitats, even though the spikes themselves do not offer any advantage in the newly colonized habitat. Dr. Lamsdell’s theory of paedomorphic horseshoe crabs invading freshwater environments also explains the lack of freshwater horseshoe crabs today. By leaving their saltwater habitats, these horseshoe crabs tied their fate to their ability to move through freshwater. As freshwater habitats contracted and became more disconnected over evolutionary time, those horseshoe crabs became more vulnerable to extinction. Eventually, freshwater horseshoe crabs faced extinction while their saltwater relatives survived to this day. The mystery of the freshwater horseshoe crabs shows these so-called “living fossils” are more than capable of adapting to changing environments, but that doesn’t mean they can overcome any challenge. Dr. Lamsdell points out that habitat degradation and climate change could threaten the persistence of modern-day horseshoe crabs. Horseshoe crabs are a fascinating reminder of changes to our world over millions of years, and they, as well as their habitats, are worth our consideration and protection. About the authors: Brian Lovett is a PhD student in Dr. Ray St Leger’s lab studying mycology and genetics in agricultural and vector biology systems. He is currently working on projects analyzing mycorrhizal interactions in agricultural systems, the transcriptomics of malaria vector mosquitoes, and the genomes of entomopathogenic fungi. Morgan Thompson is a MS student in Dr. William Lamp’s lab studying plant-insect interactions in agroecosystems. She is currently working on a project to connect belowground soil microbial and plant root interactions to aboveground insect herbivory. Works Cited: Lamsdell, J.C. 2016. Horseshoe crab phylogeny and independent colonizations of fresh water: ecological invasion as a driver for morphological innovation. Palaeontology 59(2): 181-194. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed