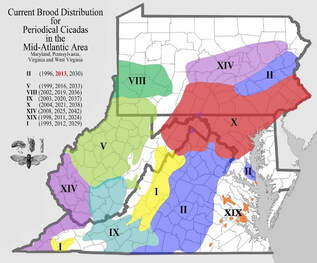

Mike Raupp Mike Raupp In the spring of 2004, millions of 17-year cicadas emerged from the ground. They crawled over trees, houses, and cars. They molted leaving exoskeleton shells on every surface. Birds feasted. Squirrels gorged themselves. Newly planted trees suffered. Children tiptoed though carcasses on their way to school. Parents scraped goo off their car’s wheels. The air vibrated with the cacophonous sound of cicadas. Then they were gone. But next year they are coming back. Whether you anticipate it with dread or excitement, they are coming again. In his colloquium presentation to the UMD Entomology Department, Dr. Mike Raupp, an emeritus entomology professor at the University of Maryland, brought us up to speed on the coming emergence of periodical cicadas. The last time Brood X, the 17-year cicadas local to this area, emerged from the ground, entomologists were in heaven. Dr. Raupp gave numerous talks around the country even ending up on Jay Leno’s late-night show to teach about the fascinating insect. He explained how 17-year cicadas are a great opportunity to get people interested in bugs. Next year, they may be even more numerous due to recent habitat restorations and improved tree cover. There are two types of cicadas; annual and periodical cicadas. Annual cicadas emerge in July and last into September. They are fast moving, and greenish in color.  Map of Mid-Atlantic broods from Cicadas.info Map of Mid-Atlantic broods from Cicadas.info Periodical cicadas, in the genus Magicicada, appear every 13 to 17 years from May to June. They are red-eyed, sluggish, and emerge by the millions. Groups that emerge together at the same time and place are called broods, designated by a roman numeral. 17- or 13-year broods are found across the United States. Brood X is the 17-year group living in the capital region and will be emerging next spring. Of course, leaving the fate of your brood up to one year is very risky so periodical cicadas also have some individuals that emerge a little early or a little late. These “stragglers” hedge against less productive years. Stragglers that start broods of their own are called “accelerations”. The cicadas that emerged in this region in 2017 may have been an “acceleration” of Brood X. When soil temperatures reach about 64°F, cicadas emerge from the ground as nymphs, shelled in a clawed carapace. They climb on the first thing they can find and molt into a soft-bodied, white, winged adult. It takes about four to six days for their exoskeleton to harden. Then they fly to the treetops to mate. Their adult stage lasts 2-4 weeks during which the male calls to attract females with a vibrating membrane called a tymbal. Once the female is fertilized, she will lay eggs in young twigs (this can cause damage to trees). After about 10 weeks the eggs will hatch into nymphs and drop from the tree into the ground. The cicada nymphs will bury themselves 18 inches deep into the soil and feed on the tree’s xylem, a nutrient-poor root fluid, for 17 years. Dr. Raupp answered some frequently asked periodical cicada questions: Why do cicadas come out in such large numbers? The strategy behind emerging in large abundances is called predator satiation.1 The chances of any one cicada being eaten are reduced when there are millions of them. Eventually predators become full and the surviving cicadas are safe to mate. And why do they emerge every 13 or 17 years? A 2004 study modeled the interactions between predator and prey cycles and found that prey emerging in prime number years avoided overlapping with the uniform predator lifecycles.2 It is less clear how cicadas know when to emerge synchronously. However, it is likely that cicadas contain a molecular clock set by a variety of environmental factors such as light and subtle changes to the roots they eat. So how should you prepare? Wait until next fall to plant trees because young saplings will likely be killed when cicadas lay eggs in their branches. If you have vulnerable young trees, protect them with netting. If you are not comfortable with an incredible number of insects flying around your face, plan a trip out of state next May-June. Make sure your pets don’t eat too many or they could have digestive issues, but if you want to try eating a few yourself, go ahead! 1. Williams, K. S., & Simon, C. (1995). The ecology, behavior, and evolution of periodical cicadas. Annual review of entomology, 40(1), 269-295. 2. Campos, P. R., de Oliveira, V. M., Giro, R., & Galvao, D. S. (2004). Emergence of prime numbers as the result of evolutionary strategy. Physical review letters, 93(9), 098107. Supplementary materials You can help track Cicadas next year using the Cicada app: Android: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=edu.msj.cicadaSafari iOS/Apple: https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/cicada-safari/id1446471492?mt=8 More on Periodical Cicadas: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/what-are-cicadas-180975009/ Written by: Max Ferlauto, masters student in the Burghardt Lab, studying how leaf litter disturbance affects overwintering insects. Krisztina Christmon, PhD student at the vanEngelsdorp Bee lab, studying host-parasite interaction of the parasitic mite: Varroa destructor. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed