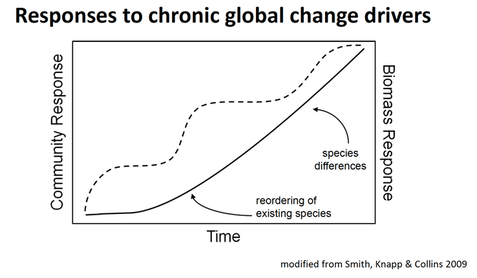

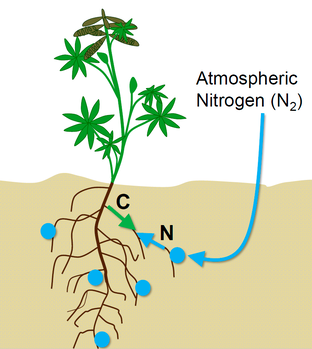

Figure 1: Dr. Kim (La Pierre) Komatsu, enjoying her fieldwork. Figure 1: Dr. Kim (La Pierre) Komatsu, enjoying her fieldwork. Since the dawn of agriculture thousands of years ago, humans have altered the global landscape. Humans transported crop species and plants across the world for feed and harvest. Agriculture allowed for modern civilization to progress, ultimately resulting in the construction of cities, urban and suburban areas. As humans move further and further away from natural landscapes, it comes at a significant cost to communities of various organisms. With these human-induced changes in mind, Dr. Kim (La Pierre) Komatsu (Fig. 1) of the Smithsonian Environment Research Center studies plant communities and connections to ecosystem processes. Dr. Kim investigates interactions between plant communities and plant biomass accumulation, insect herbivores, and nutrient acquisition, always considering how global change affects such interactions.  Figure 2: Theorized effects of human-induced changes on plant communities. Figure 2: Theorized effects of human-induced changes on plant communities. Expanding her scientific interests to a large scale, Dr. Kim and her colleagues synthesized data from 105 resource manipulation experiments around the world to determine changes in plant communities and biomass accumulation over time. They compared control plots to experimentally manipulated plots, looking specifically for changes to the types or numbers of plant species (Fig 2). Overall, they found that the total number of plant species in a community did not change in response to resource manipulation. However, a closer look at the different types of plant species revealed overall community differences in dominant species, showing greater differences when more factors were simultaneously manipulated. Additionally, when studying connections between physiological changes in plants and alterations to overall community structure, Dr. Kim and her colleagues determined that different factors play greater roles at different time periods. For instance, water and soil nitrogen contribute strongly early on whereas species differences make a greater difference to biomass almost a decade later. Ultimately, Dr. Kim concludes that human changes differentially shape plant communities in a multivariate way.  Figure 3 Rhizobia bacteria trade atmospherically fixed nitrogen to legumes in exchange for carbon. Figure 3 Rhizobia bacteria trade atmospherically fixed nitrogen to legumes in exchange for carbon. Dr. Kim shifts her discussion to legumes as a model system. Legumes are a great system to work with because they are widespread invaders all around the world, have large impacts on ecosystem function, and interact with rhizobia bacteria that are nitrogen fixers and can have a big impact on the cycling of nutrients in the ecosystem. Legumes have a horizontally transmitted mutualistic relationship with rhizobia bacteria. Rhizobia bacteria trade atmospherically fixed nitrogen to legumes in exchange for carbon (Fig. 3). Rhizobia are not maternally transferred. The seeds disperse to the ground and rhizobia disperse into soil from senescing nodules. The seedlings are infected by soil-dwelling rhizobia. Invading legumes get their rhizobia associates from novel associations (generalist), co-invasion with familiar associates (specialist), and everything is everywhere (specialist). Dr. Kim published a study using 514 native isolates and 305 invasive isolates, which were sequenced at Institute for Genome Sciences at the nifD loci. 19 unique genotypes were investigated in the study. Interestingly, invasive and native legumes do not share rhizobia genotypes for the most part. The Spanish broom and Gorse genotypes from native range were found to be 98% similar. Strikingly, it was found that invasive legumes amplify their familiar mutualists in soil rhizobia communities and common restoration techniques can restore soil rhizobia communities. Dr. Kim concludes her talk with discussion of future directions concerning identifying and addressing needs of stakeholders. An open stakeholder-driven question revolves around how to reduce pest damage without large-scale pesticide use. Another unresolved stakeholder-driven question concerns what grazing strategies are feasible during multiyear droughts. Written by: Morgan Thompson (MSc) at Lamp lab, studied: the effect of potato leafhopper (Empoasca fabae) feeding on biological nitrogen fixation in alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Mike Nan PhD student in the St. Leger lab studying how circadian rhythms affect Metarhizium infection of Drosophila. Krisztina Christmon PhD student at vanEngelsdorp lab studying the host-parasite-pathogen interaction of honey bees. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed