Drainage ditches as valuable sources of spider diversity and abundance for adjacent croplands12/1/2020

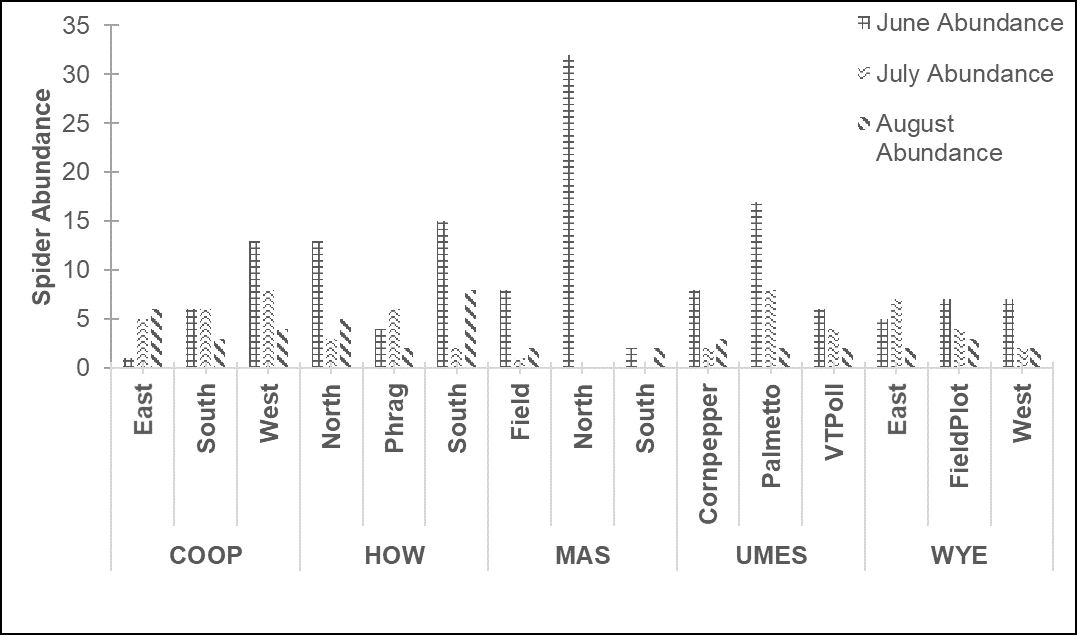

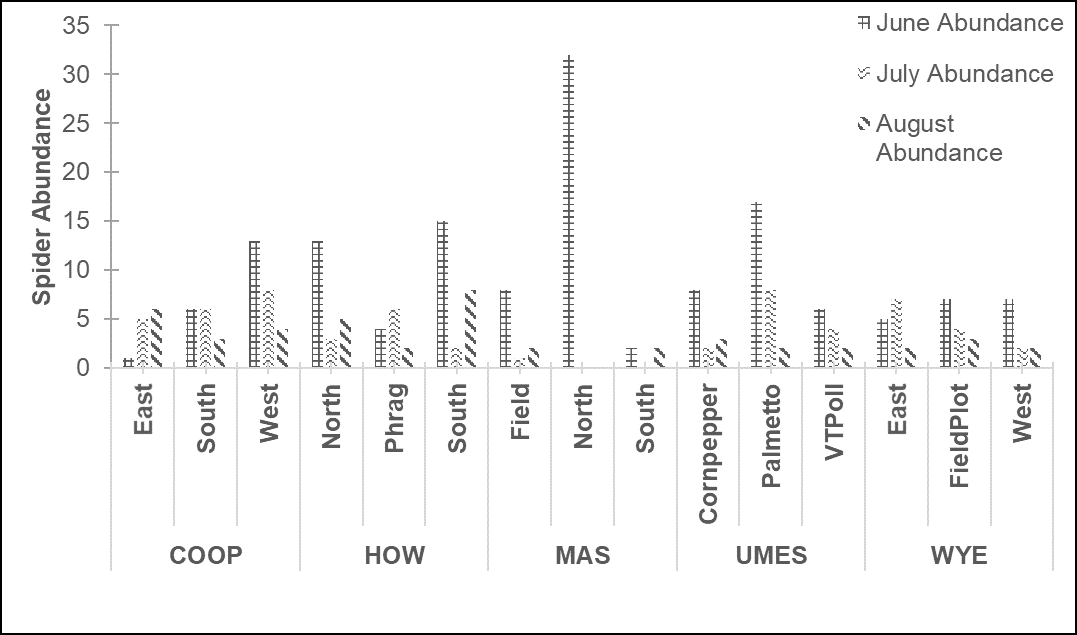

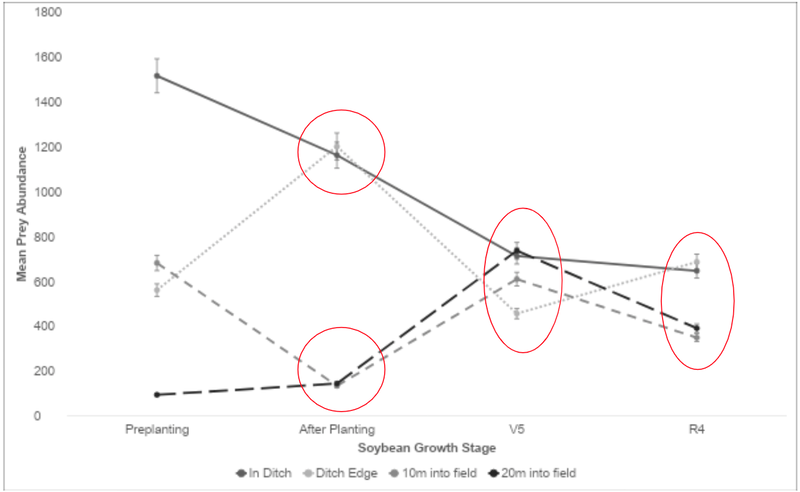

written by: Eva Perry and Lindsay Barranco At the beginning of his Entomology Department exit seminar presentation, graduate student Dylan Kutz asked his zoom-viewing audience “Who cares about spiders?” and “Why study drainage ditches?” – two questions that immediately grabbed everyone’s attention. Over the past three years Dylan has proven himself to be an adventurous and fearless researcher – sampling agricultural cropland drainage ditches for spiders in order to ascertain how they may facilitate natural pest management practices by supporting spider populations. Dylan explained that he undertook his research because he had a longstanding interest in spiders and in his undergraduate days, worked extensively with wolf spiders. In addition, prior lab work in agricultural drainage ditches along soybean cropland of the Eastern shore of Maryland inspired this project, and focused his efforts on understanding the composition of spider assemblages in drainage ditches in relation to plant assemblages. Spiders are abundant and efficient predators, and being generalist feeders will eat pest insects, vertebrates and other spiders. Additionally, spider diversity in general is vast, and there is much to learn about them in agricultural settings given that spiders eat pests in croplands in different ways. Spiders have two basic needs: prey and habitat. Each spider species might catch prey in different ways – some spiders make expansive webs like orb weavers, where the large intricate circular web needs to be attached to taller vegetation; other spiders may dwell close to the soil, and be less reliant on vegetative growth. Dylan chose agricultural drainage ditches for his work because they suit a range of strategies – a ditch flanked on each side by longer growth vegetation, which is relatively undisturbed can provide the ideal habitat for spiders until the soybean crops grow, thereby allowing spiders to migrate into the crops eventually to hunt for prey. It was first necessary to ascertain the answer to two key questions: first, the diversity and abundance of spiders in drainage ditches, and second, how plant assemblages in the drainage ditches might influence these factors. Diversity and abundance of spiders was evaluated within 15 drainage ditches on five different eastern shore farms. The drainage ditches varied by location – some were more stream-like, some look like puddles, while some are dry ditches with little to no vegetation. He caught spiders by using foliage sweeps and ground litter samples, then set about identifying spiders to the genus level. In 2017, his first field research season, Dylan identified 44 different plant families and 96 plant genera, the most common plants being common golden rod and poison ivy. Across all ditches he found 15 different spider families and 25 spider genera. The most prevalent were the striped lynx spider (Oxyopes spp.), which preys upon multiple crop pests including stinkbugs, caterpillars and spotted-winged drosophila, and employs a stalking feeding strategy; the jumping spider (Habronattus spp.), an arachnid predator that also uses a stalking feeding strategy, and whose jumping attacks allow it to capture larger prey; and the long-jawed orb weaver (Tetragnatha spp.), which uses a web building feeding strategy and is typically found in vegetation near water. Spiders collected from each ditch indicated that abundance varied by drainage ditch throughout the season, but that these assemblages were similar by farm. Additionally, spider assemblages from ditches at the same farm tended to be similar (Figure 1). Plant assemblages and ditch characteristics did not predict spider diversity in ditches. Understanding which spiders and how many use drainage ditches is only a part of what Dylan sought to understand about these unique habitats. During the 2018 and 2019 field seasons, he collected data with the aim to answer three subsequent questions: how spider assemblages in ditches change over the growing season, which spiders are colonizing croplands from the ditches, and if environmental factors play a role in this colonization. Dylan’s sampling of drainage ditch and soybean cropland assemblages revealed some notable strategies by particular species. Across the growing season, the wolf spiders Pardosa milvina and Tigrosa helluo were found at all sampled locations, in contrast to the wolf spider Rabidosa rabida which was found exclusively within the ditches. Two members of the jumping spider family were found to colonize soybean croplands from the drainage ditches over the course of the growing season: Sitticus concolor and Zygoballus rufipes, which were found to be present in croplands during the latter half of sampling. All five of these species showed fidelity to their respective strategies in both field seasons. The 2019 field season data revealed a strong positive relationship between mean spider abundance and mean prey abundance (Figure 2). To further understand this relationship, Dylan examined prey abundance for the different habitat types he sampled across the growing season. He found that when soybeans are first planted, mean prey abundance is very high in drainage ditches and very low in crop fields; these abundance means begin to converge in the latter half of the growing season (Figure 2). Increased prey availability in crop fields combined with the simultaneous decrease in prey availability in drainage ditches may explain spider colonization strategies that move from ditches to fields as the growing season progresses. These findings not only highlight the importance of naturalized drainage ditches adjoining cropland, but contributes to the important body of research that confirms the importance of spider populations in crop pest management.

Following graduation from the University of Maryland in July 2020, Dylan was hired as an entomologist with American Pest, a company whose work involves a contract with the National Institutes of Health for the monitoring and eradication of pests within research facilities.All images used were taken by Dylan Kutz and were presented at the UMD Entomology Colloquium on 11/13/2020. References: Bradley, Richard A. 2013. Common Spiders of North America. Oakland, California: University of California Press Nyffeler, M., W. L. Sterling, and D. A. Dean. "Insectivorous activities of spiders in United States field crops." Journal of Applied Entomology 118.1‐5 (1994): 113-128. Uetz, George W., Juraj Halaj, and Alan B. Cady. “Guild structure of spiders in major crops.” Journal of Arachnology (1999): 270-280. Written by: Eva Perry is a PhD student in the Burghardt Lab researching how plant-insect interactions are altered by human influences, and the ways in which these disruptions affect natural predators. Lindsay Barranco is a Masters student at the vanEngelsdorp honey bee lab working on wildflower meadow projects with partners throughout the State of Maryland and is researching the establishment of ground nesting native bee sites within small scale wildflower plantings. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed