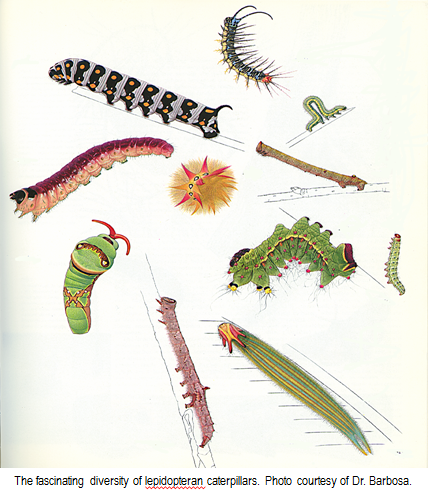

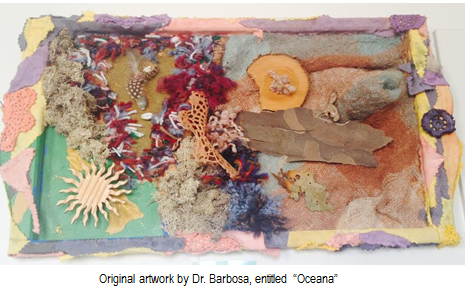

A reflection on the career of a recent retired faculty member of the Entomology Department Imagine having to walk across the George Washington Bridge just to find some green- green grass, trees, maybe a couple of flowers. This is what Dr. Pedro Barbosa, Entomology Professor Emeritus of the University of Maryland, did throughout his childhood. Growing up in New York, Dr. Barbosa didn’t see much nature in the city and since his family didn’t own a car, he would frequently walk across the GW Bridge to New Jersey for that purpose. Apart from wanting to escape the concrete jungles of New York, Dr. Barbosa didn’t realize his interest in entomology until he started his undergraduate college career. He attended the City College of New York, a school on the edge of Harlem. He planned on becoming a medical doctor, but soon realized he disliked the nature of being pre-med at that time. Despite this, Dr. Barbosa always had a passion for science. As a self-described “bad student”, Dr. Barbosa only did well in the classes he liked, but those classes were all biology related. Many of the Biology teachers he got to know had a background in entomology, and drew him into the field. Once he became interested, it came easily to him. “Because I was learning about things I cared about, I did well,” he says.  Dr. Barbosa went to the University of Massachusetts for his master’s degree and stayed there to complete a Ph.D. “I asked my advisor what it would take to be successful, and he said I would need to have 12 publications before I finished my Ph.D. I didn’t know any better so that’s what I did, I graduated with 12 publications,” he reflects. “I was, as I used to say to myself, street smart, but world stupid. However, he has always been so grateful that his advisor did not underestimate his potential because of his background. Dr. Barbosa focused his Ph.D. work on mosquitos. However, once he began an Assistant Professor position at Rutgers University, he noticed that many others faculty members were studying mosquitos, so he switched his focus to an invasive species, the gypsy moth. The gypsy moth was causing widespread damage, feeding on over 400 different plant species, especially trees. He became interested in the broader levels of ecology and entomology, and how things really tied together. Dr. Barbosa was especially fascinated by tri-trophic level interactions, such as insect-plant-natural enemy and pest-host-parasitoid interactions. Gypsy moths affect different plant species to various degrees. Dr. Barbosa reasoned that if he could get specific information about the severity of harm to different tree species, he could estimate likely levels of damage and predict which sites were more likely to experience a severe outbreak of the pest. Dr. Barbosa’s studies revealed that secondary plant compounds, among other things, played a role in the rate of development, size, and reproductive potential of the insects that feed on them. Secondary plant compounds are chemicals that defend against herbivory. Thus began Dr. Barbosa’s work with other plants such as tobacco and looking into how these defensive compounds, nicotine in this case, affected the insects that feed on tobacco, as well as the parasites that attack these insects.  Dr. Barbosa’s research went on to look at continued to focus on tri-trophic level interactions in tree feeding insects. He believes the most notable of his studies was work done with caterpillars and identifying levels of parasitism on two different tree species. Caterpillars were collected from the two tree species and examined for parasitism. Differences in the level of parasitism were found in caterpillars of the same species but found on two different tree species in the same habitat. For example, when looking at Box Elder trees and Willow trees, Dr. Barbosa and his students found that the caterpillars of the same species were twice as likely to be parasitized on Box Elder trees than on Willow trees. The question of what was leading to these different levels of susceptibility led to a research project done by one of Dr. Barbosa’s graduate students. This student used a technique to study the mechanism of a caterpillar’s defense against parasitism. A glass bead dyed red, representing the egg of the parasitoid, was injected into caterpillars. The “egg” was then surrounded by blood cells in the caterpillar, which formed a capsule. Once encapsulated, a real egg would die. This process differed depending on the tree species on which caterpillars occurred, suggesting that tree leaves consumed by caterpillars may contain a chemical which affects the caterpillar’s ability to defend against a parasitoid. Dr. Barbosa loves working with students. He describes his role as evolving from advisor to occasional therapist, to friend. He realized that students really took what he said to heart. “I was speaking to one of my students one time who said ‘remember at that meeting in Toronto, we were walking outside and you said…’, and I thought, wow! How did you remember that, it was years ago! That’s when I realized students remember everything. It really proves you have an impact.”  Dr. Barbosa now spends time with his grown children and his six grandchildren, and also enjoys bronze casting and developing multimedia art pieces. You can see his love of art on his office walls, where masks from Mexico, New Guinea, and Central America share space with his own creations made of wood, cloth, sponges and bark, including “Oceana” pictured below. His love of art is driven by a quote he once heard, attributed to Arhur M. Sackler, who presumably said, “Science is a discipline done with passion, and Art is a passion done with disciple.” Though he retired in 2010, Barbosa still continues his work with fervor. He continues to publish and work with students, adding to an already successful career consisting of over 175 publications, over 100 undergraduates, graduates, and post docs mentored, and countless numbers of special awards and recognitions. After completing one book last year, he recently finished a Manual on Insect Histology techniques and is starting to write a book on Animal-Plant Interactions. “I can’t imagine life without entomology,” Dr. Barbosa said. “There is wonderfulness in finding passion and going for it, and I get to do it surrounded by great people.” Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed