|

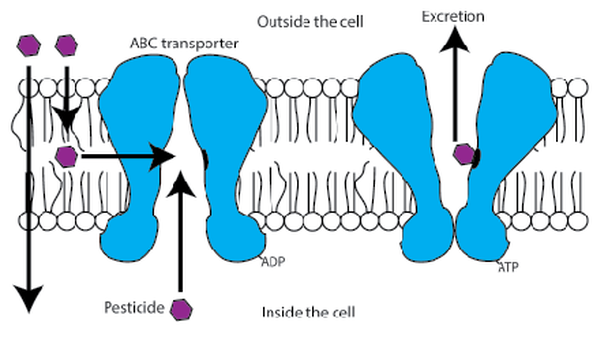

Post by Ryan Gott and Nathalie Steinhauer Colloquium this week was a special treat as Grace Kunkel defended her Master’s thesis “Investigatingin vivo honey bee toxicology and whole honey bee hive dynamics using fluorescent dyes.” Grace’s work focused on two different levels related to honey bee health: the individual honey bee and the entire honey bee colony. Collapsing colonies have been in the headlines since 2006, and with finger-pointing at many possible perpetrators. These potential causes of Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) include bee parasites, bacterial and viral diseases, fungi, poor nutrition, and chemicals (but not cell phones!). While current research suggests that CCD is most likely caused by a combination of these factors, Grace decided to focus on how chemicals may be affecting the honey bees. While the most suspect chemicals include pesticides and fungicides, using these chemicals in experiments is complicated and expensive. As a solution Grace used dyes that were chemically similar to specific pesticides. This allowed her to not only save money, but also easily track the dyes though individual bees and colonies. When honey bees are exposed to pesticides, proteins called ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABCs) form the first line of defense by actively sequestering the chemicals in the honey bee’s gut to be excreted (Fig. 1). If these ABCs are inhibited, pesticides can build up to dangerously toxic levels in the honey bee’s blood. Grace found that both excretion by ABCs and inhibition of ABCs can be studied in individual honey bees using dyes that mimic the behavior of pesticides. If honey bees encounter ABC inhibitors in their environment, this could sensitize them to pesticides. The dynamics of a chemical in a whole colony, however, can be vastly different from those in an individual bee. When chemical exposure in a honey bee colony is explored, typically the chemical is applied directly into the hive through either sugar syrup or pollen patties. Grace questioned whether those two methods of chemical delivery were truly equivalent or if they lead to different distributions of the chemical in the colony. To explore this she once again used dyes as chemical surrogates. By incorporating dyes into syrup and patties, she could track their movements through each component of the colony, from honey to wax and from larvae to adult bees (Fig. 2). Dye delivered in sugar syrup gets stored and accumulates in the hive, while dye in pollen patties does not. Grace believes this shows that pollen patties are directly eaten by the bees and not stored, unless the patty is eaten while the bees are producing royal jelly. Royal jelly is a highly nutritious substance produced to feed future queens, so chemicals that end up in royal jelly could potentially affect future generations of bees. Grace’s findings have important implications for colony health. Behavior of expensive pesticides in a honey bee colony can be mimicked using similar dyes for a fraction of the cost. Delivery of chemicals through pollen patties equates to an “acute” exposure to a chemical, while the stored syrup would be a “chronic” exposure. This means the method of chemical delivery makes a big difference, and future researchers using actual pesticides in colonies should choose their delivery method wisely. About Nathalie: Nathalie Steinhauer is a PhD student working in the vanEngelsdorp lab. She studies the risk factors associated with beekeeping management linked to increased honey bee colonies mortality.

About Ryan:Ryan Gott is a PhD student in the lab of Bill Lamp. Ryan studies environmental toxicology and environmental risk assessment with a focus on developing biomarkers for chemicals that interact with ABC transporters. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed