|

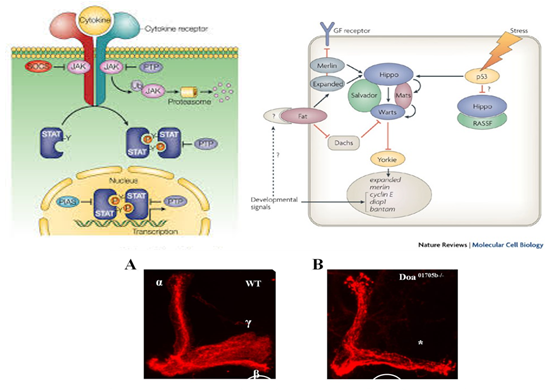

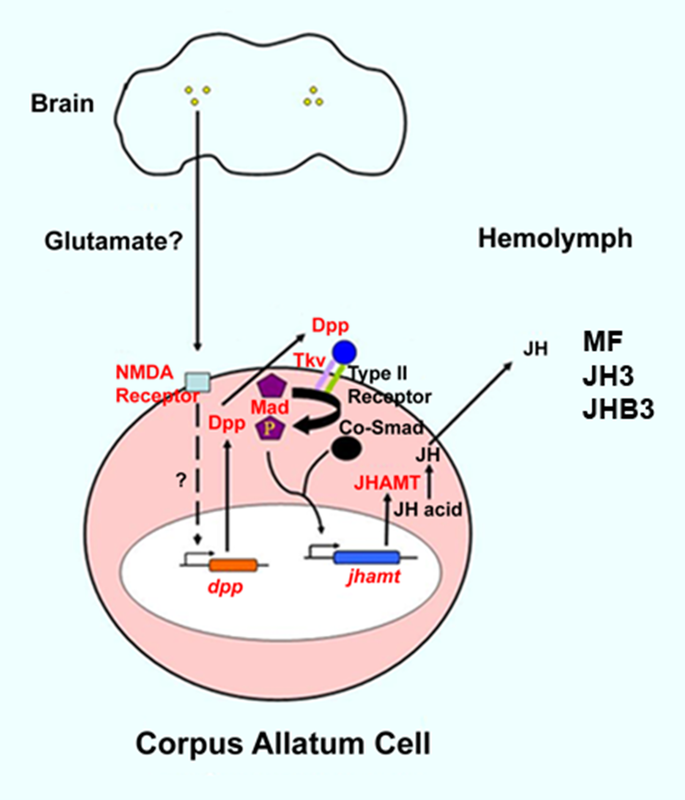

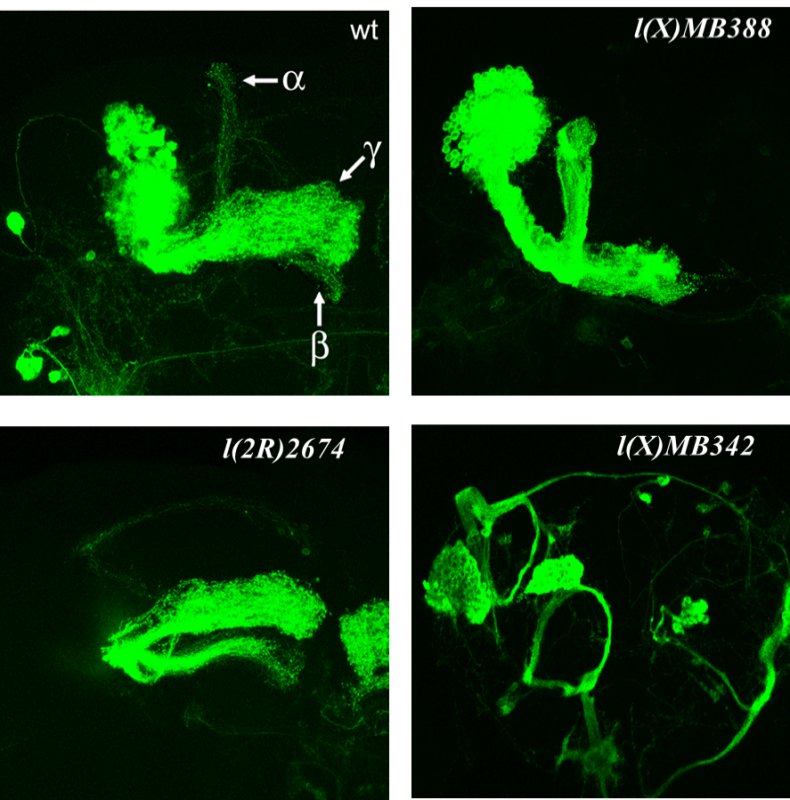

The generation of a mature insect from its larval stage might seem unimaginable at first. For instance, how can a worm-like larva transform into a winged butterfly? They are completely different, not only in their appearance but their physiology and behavior as well. With the correct cellular and molecular mechanisms, however, the entire process of metamorphosis can be properly coordinated, often in a swift and timely manner. This, and questions concerning the details of this phenomenon, is precisely the subject of study for Dr. Jian Wang. After receiving degrees at Nanjing Agricultural University andShanghai Institute of Entomology, Dr. Wang went ahead to investigate the aforementioned topic, with a concentration specifically in the laboratory fruit fly, known as Drosophila melanogaster. The “lab rat” Drosophila, while a useful genetic model, can also serve as a model for insect physiology. Thus, this animal can provide crucial information on the function of genes and signaling pathways that are often, and conveniently, transferrable to their vertebrate counterparts. At the same time, scientists who study Drosophila can apply novel information learned about insect hormonal changes, reproduction, behavior etc. to insects at large, thereby providing a centralized method for studying these invertebrates as a whole.  The image above is a compilation of just a few different genotypes/phenotypes of Drosophila; the specialized field of uncovering what different genes do, many times by creating mutations and observing the resulting phenotypes, is known as functional genetics/genomics. (http://www.drosophila-images.org/2006.shtml) One of the main questions that Dr. Wang is interested in solving is the pathway of Juvenile Hormone (JH) signaling, including the identification of signaling molecules and receptors that compose this pathway. Initial evidence showed that the ablation, or gross removal, of a neuroendocrine structure known as the corpus allata (CA) resulted in pupae that would die prematurely before they could emerge as adults. Thus, the CA was identified as a major determinant in insect metamorphosis. Next, a series of experiments showed that when the CA was destroyed, it was possible to partially rescue the lethal developmental effects by adding any of 4 different “Juvenile Hormones”, 3 naturally-occurring hormones and the other a well-known artificial analog of this hormone. Eventually, a complete picture was formulated for the juvenile hormone pathway: the brain stimulates the cells of the CA with neurotransmitters to produce dpp, a morphogen involved in development; and this molecule activates the TGF-β signaling pathway to produce JHAMT, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of any of three juvenile hormone isoforms. The other main topic of Dr. Wang’s research is the function of genes that are important to the development and maintenance of the nervous system. Much of this work uses a genetic mosaic technique, which can generate parts of an animal that are completely mutant for a particular gene. One well-studied brain structure in the Wang lab is the mushroom body. Critical to formation and retrieval of olfactory memory, the mushroom body is a structure composed of bundles of dendrites and axons. Ubiquitous in insects, and possessed by some non-insects as well, this suborgan has a characteristic V-shaped axonal branching pattern. The degeneration and/or malformation of these axonal lobes has been under intense study in the Wang lab, whereby the function of a gene can be deduced by the aberrant resultant phenotype observed following the generation of a mutation for that mushroom-body expressing gene. Of particular interest in the past decade or so was the function of DSCAM, a protein involved in neuron synaptic formation, the precise location where two neurons meet and communicate at the molecular level. A multitude of mutations were generated for the gene producing this protein which resulted in two important discoveries. Firstly, a DNA sequence analysis showed that the Drosophila gene producing DSCAM is conserved, in terms of nucleotide base pairs, with a gene found in humans. Secondly, through a clever transgenic assay, it was found that pupation rate, and to a lesser extent eclosion rate, could be partially rescued by overexpressing different forms of human DSCAM in mutant flies unable to produce any DSCAM of their own. These two experiments provided evidence that human and Drosophila DSCAMs not only have a conserved sequence, and are possibly evolutionarily related, but that they are functionally conserved as well. Currently, the Wang Lab is continuing its quest to uncover more genes that play a critical role in the development of the Drosophila nervous system, using the mushroom body as the experimental tissue of choice. The senior graduate student, Lijuan Du, is currently investigating the overlap between the Hippo pathway and the JAK/STAT pathway. Over the years, she has found evidence that one particular gene is regulated downstream by both of these pathways. These pathways are crucial in regulating the cell cycle, carefully guiding cells through proper rates of cell proliferation and programmed cell death. The other member and writer of this blog, Justin Rosenthal, is beginning his second year in the Wang Lab. The focus of his research is the function of a single gene, Darkener of apricot(Doa), in ensuring neuronal viability through the drastic changes of metamorphosis. He has already confirmed work done by previous students that this gene is necessary for survival of the y-lobe of the mushroom body and is now devising experiments to test the role of the individual variants of this gene and the functional importance of some of the exons, or the coding parts of the gene.  The two top images show the JAK/STAT (left) and hippo(left) pathways, delineating the intricacies of each. The bottom photo is of two mushroom bodies, visualized with a red fluorescent marker. The left is the wt condition and the right it the mutant condition. One can easily see the stark differences, wherein the mutant mushroom body is completely missing the medial-branching y-lobe(top left: http://www.nature.com/nri/journal/v3/n11/full/nri1226.html), (top right: http://www.nature.com/nrm/journal/v8/n8/fig_tab/nrm2221_F3.html) (bottom: Qiong Yao) Article published by Dr. Wang and others: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S096517481100110X Article related to neuron patterns in Drosophila:http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v497/n7447/full/nature12063.html About Justin:

Justin Rosenthal received his undergraduate degree from the University of Maryland-College Park in 2011 in the Biological Sciences, with a concentration in neurobiology/physiology. Upon beginning his PhD. Program here, Justin began investigating the role of a particular gene, darkener of apricot(Doa), in promoting neuron survival through the pupal stage of insect life, i.e. metamorphosis. Building upon previous research, it became ever more convincing that without this gene certain neurons within aDrosophila’s brain will not survive until adulthood. Currently he is working out the purpose of specific exons and isoforms of this gene, as several variations exist. Further research will likely include expansion of this investigation into other non-nervous tissue. Overall this information will provide a molecular model for how cell death, especially in neurons, proceeds. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed