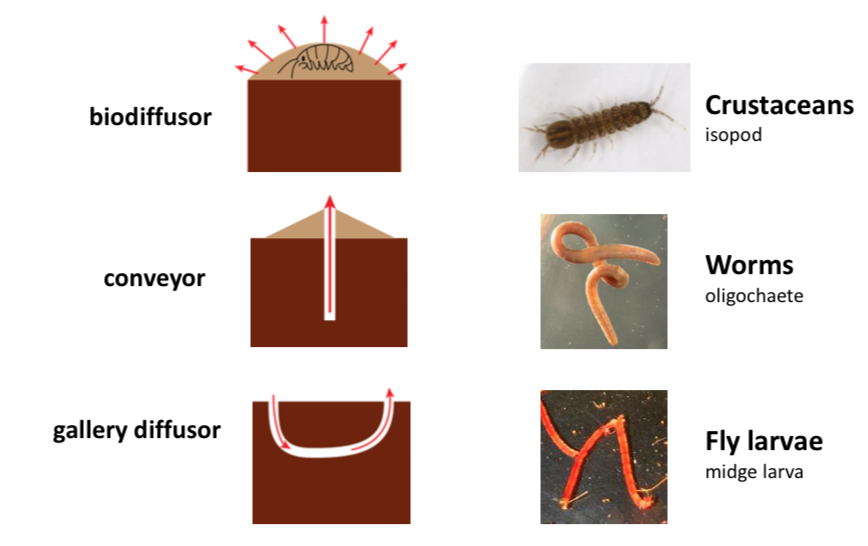

Ever wondered what creatures are lurking in your murky backcountry drainage ditches? Well, so has freshly-vindicated Dr. Alan Leslie. Through months of trudging through these mucky landscapes, he has sought to bring to light what is happening in the turbid depths of these ditches. Not only does the soil within contain a significant proportion of the Earth’s diversity, but these specialized environments are formed in juxtaposition of constantly fluctuating aquatic ecological systems and soil chemistry composition. The habitat acts as home to many critters that provide critical support for our agricultural food systems, energy cycling, and often serve as indicators for water quality. On the Eastern Shore of Maryland, 40% of the poorly drained land surface is used for agriculture, which places these ditches at an intersection of a significant proportion of water eventually trickling into our streams, rivers, and oceans…and drinking water. Think of these ditches not just as sporadic texture added to the otherwise flat agricultural landscape, but acting mitigation wetlands serving to reduce leaching of herbicides and pesticides; promote denitrification; and retain nutrients where they are most needed. The community mostly consists of organisms that are able to thrive in less than pristine conditions faced with constantly changing water volumes and chemical inputs. These impaired streams are brimming with different ecosystem engineering taxa that work to do similar jobs, even in the face of constant construction and deconstruction of the environment. So who lives in the neighborhood? Alan discovered that 92.5% of everyone in the local ditch community lives at the water-sediment interface, right on beachfront property. Is it water quality that determines who settles down in a ditch?Surprisingly, no. Alan found that these burrowing invertebrate inhabitants did not correlate with water quality but did correlate with the size of the ditch. Specifically, the cross section and flow the water in the ditch. Size mattered most regarding retention of moisture, which affects the community taxa. Smaller ditches dried out more, which fostered more Isopoda (aquatic sow bugs) than the perennially wet, larger ditches that the Haplotaxida (aquatic worms) and Diptera (fly larvae) inhabited. So who does what? Alan decided to do a closer inspection of burrowing invertebrates’ different gardening techniques and how they could change nutrient cycles in the ditches. Using soluble reactive phosphate (SRP) as an indicator nutrient, he was able to observe how different techniques of sediment perturbation, sediment particle size, and changing water composition/quality would affect the release of SRP into the environment. He handcrafted miniature microcosms to simulate different perturbation types using three major invertebrate inhabitants: bio diffusors, large conveyors and gallery diffusors. SRP is the amount of phosphorus (P) available to be used for growth without any further required conversion. Although the results varied depending on factor combination used in these isolated microcosms, Alan expects an overall decrease of P release into the surface water due to the complexity of invertebrate burrower community within a realistic ditch ecosystem. Feeling inquisitive after your journey through boundless rows of Eastern Shore cornfields on your way to the beach? To delve deeper into the drainage ditch depths, you can peruse Dr. Leslie’s most recent publication in Environmental Entomology. Lauren Hunt is a master’s student in Cerruti R.R. Hooks’ lab who is conducting research on sustainable agricultural practices. She is currently studying effects of habitat manipulation as a pest control tactic in organically managed cropping systems.

Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed