Fall 2015 Colloquium: Dr. Steve Frank, Associate Professor at North Carolina State University11/19/2015

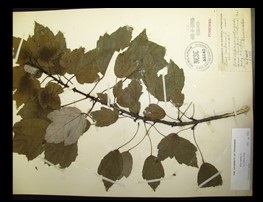

Increased Temperature Aids Pests in Overtaking Cities It has been observed for over one hundred years that plant insect pests such as scales, white flies, and thrips are more prevalent in urban areas than in forests. Many scientists have sought to understand this phenomenon with hypotheses on enemy release and abiotic influences. Enemy release relies upon the absence of natural enemies such as predators and parasitoids of pest insects in urban areas. In the resulting absence of enemies, populations of pests are allowed to build to extraordinarily high numbers. Abiotic influences, on the other hand, are aspects of the physical environment such as temperature that lead to increased population sizes. Dr. Steve Frank of North Carolina State University argues that the main driver in the high occurrence of pests in urban areas is not natural enemies but increasing temperatures in cities. Dr. Frank and his lab work with scale insects in Raleigh, North Carolina to elucidate the importance of temperature on pests, how pests impact tree health, and predicting effects of global warming. Does temperature affect the insect pests? Gloomy Scale, Melanaspis tenebricosa, is an excellent model for studying the importance of temperature on pest insects as it has a long history of localized high abundance in Raleigh. The earliest report on gloomy scale by Zeno Metcalf in 1912 heralded this insect as being the most important shade tree pest in North Carolina. Since that report, it has remained in high numbers in Raleigh but not in neighboring forest areas. Looking at heat maps of the area, Dr. Frank’s lab surveyed red maple trees within a gradient of temperatures in Raleigh and observed that gloomy scale abundance increased with temperature (Dale and Frank. 2014b). The question of why they were seeing this trend spurred additional investigation. (Left) Gloomy scales covering the tree’s branch making the bark appear rough and bumpy. Photo by Adam Dale. (Right) Zoomed in on the branch, you can see that each bump is an individual scale with its brown armor blending into the branch. The red dot in the middle is scale insect with its armor removed revealing the soft insect underneath. Photo by Matt Bertone The lab found that body size as well as egg production increased with temperature (Dale and Frank. 2014b). With increased egg production there is a corresponding increase in population growth, which helps the gloomy scale reach high densities. In short, because temperatures are higher in cities, gloomy scale is able to respond with increased body size, reproduction, and growth rate. Does temperature and pest abundance affect tree health? Dr. Frank’s lab wanted to investigate the effects of a possible interaction between warming and pests on tree health. To test this, they assessed the condition of all the red maple trees studied previously and then expanded the study to analyze 8462 trees inventoried by the city of Raleigh (Dale and Frank 2014a). Results showed that trees in hot locations, where scale abundance was therefore higher, were more than twice as likely to be in poor condition than trees in cold locations. The lab measured the water potential of the trees to help explain the physiological link between temperature and tree condition. Water potential in trees is linked to the ability to move water from the roots to the shoots. Dr. Frank’s lab found that water potential decreased with increasing site temperature, meaning that the trees were under higher drought stress in hotter areas (Dale and Frank 2014a). Linking temperature effects to both pest insects and tree health gives a holistic picture of the health and functioning of trees in urban landscapes. Can we predict the effects of global warming?  Historical red maple sample from an herbarium, which was assessed for scale abundance. (Youngsteadt et al. 2014. Global Change Biology) Historical red maple sample from an herbarium, which was assessed for scale abundance. (Youngsteadt et al. 2014. Global Change Biology) As urban areas are hot patches in the broad landscape, perhaps they can be used as proxies to look at the future of climate change. To tackle this idea, Dr. Frank’s lab used historical samples of red maple from herbarium collections, dating as far back as 1895. These samples were collected from rural areas around the southeast, and scales remain visible on them. The researchers found that the change in gloomy scale abundance with temperature variation was congruent across rural historical and modern urban samples (Youngsteadt et al. 2014). They also resampled trees at some of the historical sites and found that in most cases, the rise in temperature over the last several decades has led to an increase in gloomy scale abundance (Youngsteadt et al. 2014). Thus, it seems plausible that the relationships and patterns between scale insects and temperatures in cities could be used as an informative tool to predict potential outcomes of global climate change. What can we do today to help manage effects of temperature in cities? Urban areas around the world are becoming larger and hotter. As Dr. Frank’s lab has shown, the increase in temperature leads to more pest outbreaks, and these pest outbreaks have negative consequences for ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration and air purification. As temperature increases, cities will need to consider how to manage the effects on urban trees. For example, pest outbreaks may start occurring earlier in the season (Meineke et al. 2014), so scouting for pests should be increased. Cities should also try to plant more tree species and varieties that are resistant to the effects of increasing temperature on pest outbreaks and water stress. This may mean breeding or genetically modifying new varieties for cultivation. Concluding Thoughts In a broader sense, the decrease in urban forest canopy cover will have many negative effects both on wildlife and on humans. Studying urban trees will help identify problems, and potentially elucidate future effects of climate change. These effects threaten not only urban trees but also natural areas; therefore, understanding the impact of temperature on urban trees can help predict and prepare for the future of climate change across temperature gradients in landscapes. References: Dale A., S. Frank. The Effect of Urban Warming on Herbivore Abundance and Street Tree Condition. Plos One. 2014a. Dale A., S. Frank. Urban warming trumps natural enemy regulation of herbivorous pests. Ecological Applications. 2014b. Meineke E., R. Dunn, S. Frank. Early pest development and loos of biological control are associated with urban warming. Biology Letters. 2014. Youngsteadt E., A. Dale, A. Terando, R. Dunn, and S. Frank. Do cities simulate climate change? A comparison of herbivore response to urban and global warming. Global Change Biology. 2014. About the Authors:

Jessica Grant is a master’s student currently working on kudzu bug (Megacopta cribraria) pest management. For more information on her work see this site mdkudzubug.org Aditi Dubey is a Ph.D. student looking at the effects of neonicotinoid seed treatment in a three-year crop rotation. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed