|

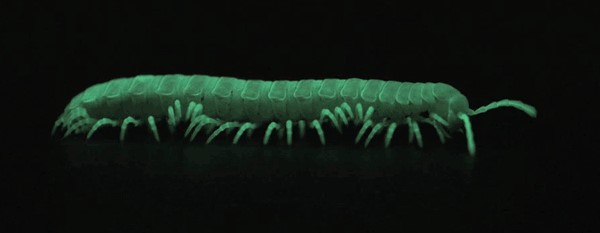

In the mountains of California there are 9 species of millipede in the genus Motyxia, that do something no other millipede on earth can do. Every night they emerge from underground burrows and begin to glow with a constant soft blue-green light, and until recently no one knew why. While emitting light makes Motyxia unique among the millipedes it is hardly novel in the animal kingdom, and animals do it for a variety of purposes. Anglerfish in the deep sea glow to attract prey, but Motyxia are vegans. Fireflies flash with light to attract mates, but Motyxia, like all members of the order Polydesmida, are completely blind, so they aren’t searching the night for a glowing partner. While working at the University of Arizona Dr. Paul Marek set out to solve this mystery. Bioluminescent millipedes are exclusively found along the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, Tehachapi, and Santa Monica mountain ranges in Southern California. They live in majestic live oak and giant sequoia thickets, where they feast on decaying plant material and are sadly eaten in turn by rodents, centipedes, and phengodid beetles. These gentle and slow moving creatures appear to lack any defense, and glowing seems like the opposite of camouflage. It seems like they’re asking to be eaten! It turns out that glowing isn’t the only shocking chemical reaction taking place in these tiny legged bodies, they’re packed full of the deadly poison cyanide. Marek hypothesized that glow of these millipedes warns potential nocturnal predators that they will be an unpleasant meal, just as the bright colors of a wasp or a poison dart frog warns predators in the daytime to stay away! Scientists call the presence of warning signals like these aposematism. To test his theory of the function of bioluminescence, Marek created millipedes out of clay, painted some of them with glowing paint, and placed them in Motyxia habitats. After a night the clay millipedes were collected and checked for signs of predation. Rodents avoided attacking the glowing clay millipedes, indicating that rodents know to avoid the green glow and it’s accompanying mouthful of cyanide. Furthermore, at higher elevations the rodent populations are greater and more diverse, which means there is a much higher risk of being devoured by a predator. Over time the millipedes living at higher elevations have coped with this disadvantage by evolving brighter bioluminescence than those living at low elevations. This brighter and stronger warning keeps hungry rodents at bay! How they produce their light remains a mystery... Video courtesy of Marek Lab Further Reading:

Marek, P.E., D.R. Papaj, J. Yeager, S. Molina, W. Moore. (2011). Bioluminescent aposematism in millipedes, Current Biology, 21, R680-R681. Pieribone, V., & Gruber, D. F. (2005). Aglow in the dark: The revolutionary science of biofluorescence. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. About the Authors: Gussie Maccracken is a PhD. student in the Mitter Lab at the University of Maryland and the Labandeira Lab at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History. She studies plant-insect interactions in the Late Cretaceous fossil record of North America. Peter Coffey is a Master's student whose research focuses on using cover crops to optimize sustainable farming economics. His current projects using lima beans and eggplant as model systems focus on plant nutrition, weed suppression, influences on pest and beneficial insects, and crop yield value. Follow him on twitter at @petercoffey. Follow Paul Marek on twitter at @apheloria. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed