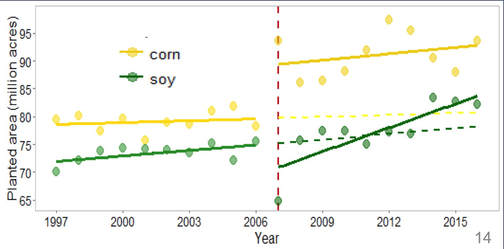

Dr. Dilip Venugopal, AAAS Science & Technology Policy Fellow US Environmental Protection Agency Dr. Dilip Venugopal, AAAS Science & Technology Policy Fellow US Environmental Protection Agency Since 2007, the US has ramped up biofuels production citing reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and decreased dependence on foreign oil as goals. While biofuels can have positive environmental impacts, the rapid increase in corn and soy acreage and intensity has had unintended consequences. As an AAAS fellow at EPA, Dr. Dilip Venugopal studies the impacts of biofuels standards programs. Once upon a time, both major political parties of the US came together with concerns about climate change, greenhouse gas emissions, and dependence on oil. The Renewable Fuel Standards Program, enacted in 2005 by President George W. Bush, aimed at producing more renewable fuels and reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In conjunction with the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (EISA), the US was moving toward energy independence and efficiency.  Figure 1 President George W. Bush signs the Energy Independence and Security Act. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2007/12/20071219-1.html Figure 1 President George W. Bush signs the Energy Independence and Security Act. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2007/12/20071219-1.html Along with these programs implemented by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, came renewable volume obligations (RVOs), a yearly quota of required biofuel production by the US. Both congress and the EPA were aware of the potential environmental impacts of such a quota, and have policies in place to limit such negative effects. In addition, the policies also included plans for detailed research monitoring potential environmental consequences. Dr. Dilip Venugopal, an AAAS fellow at the EPA, is researching these impacts of the Renewable Fuel and Energy Independence Programs. The focus of Dr. Venugopal’s work has been land use change as a key impact of these biofuel policies, and also as a driver of further environmental effects.  Figure 2 The increase in corn and soybean acreage since 1997. Red line indicates beginning of EISA Credit: Dr. Dilip Venugopal Figure 2 The increase in corn and soybean acreage since 1997. Red line indicates beginning of EISA Credit: Dr. Dilip Venugopal Between 2007-2012, cultivated cropland increased by 4.3 million acres, with most of the increases coming from land formerly used as pasture or as part of the Conservation Reserve Program. Corn was the most commonly planted crop in areas converted to cropland. After 2007, production of biofuel crops (mainly corn and soybeans) dramatically increased. Many of these changes in land use increased with proximity to biofuel refineries, and at the expense of grasslands and other natural habitats. In addition to converting land for agricultural use, agricultural practices intensified throughout the landscape, particularly in the Midwestern corn belt. Crop rotation decreased, with some records of up to nine years of corn being continuously planted in the same field. Such intensification can result in decreased soil productivity and increased pest pressure. But how many of these changes can actually be attributed to biofuel policies? Dr. Venugopal produced synthesis of published information, and correlative studies looking at the relationship between ethanol production and land-use change, corn and soy production, and corn acreage near ethanol plants. All of these factors have increased significantly after the policies began in 2007. Through synthesis of published information and his analyses, Dr. Venugopal attributes 25% of the changes in corn production, 35% of the variation in corn acreage, and 65% of the variation in soy acreage to RVOs and biofuel policies. This is an active area of research with many peer-reviewed articles over the past 3 years examining such negative impacts. While the actual attribution of environmental impacts to the biofuel policies is emerging, recent studies highlight the negative impacts. Land use changes linked to the biofuel policies have measurable negative environmental impacts. These impacts include:

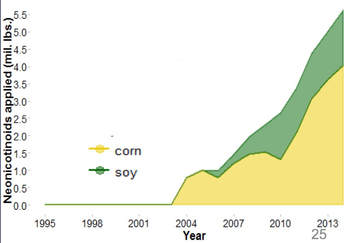

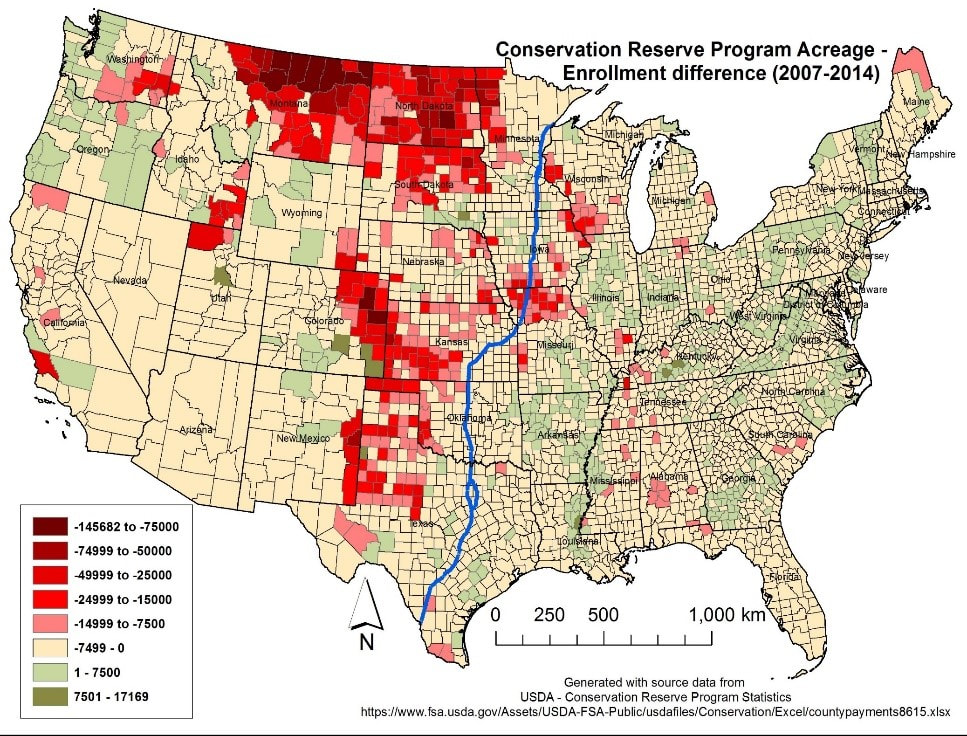

As economic demands through biofuel policies along with other factors drive the expansion of field crops, more land is converted into grain monoculture, simplifying a once complex and dynamic landscape. This lowers overall plant biodiversity, ultimately reducing the variety of available suitable habitats for other organisms, like pollinating insects. Pollinators, which are critical in the production of many non-grain crops and overall ecosystem function, require a healthy variety of food sources. Thus, with lower plant biodiversity, pollinator nutrition suffers. Additionally, measures taken to protect biodiversity within agricultural regions have become less effective. The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) is an incentive program put in place in 1985. Through CRP, farmers can be paid to not cultivate certain lands deemed sensitive or critical habitats. According to Dilip, since the introduction of the Renewable Fuel Standards Act, CRP enrollment has dropped in the regions with the heaviest biofuel production. Many factors play are role in this reduction in enrollment, including the reduction of the enrollment ceiling to its current level of 24 million acres. However, published reports indicate that biofuel policies can account for 30% of this drop. Because of this, less of the critical Midwestern grassland and wetland habitats are conserved, resulting in lower habitat availability and connectivity for organisms like migrating Monarch butterflies.  Figure 4 The increase in neonicotinoid seed treatments in corn and soybeans from 2003-2013. Credit: Dr. Dilip Venugopal; original data from Douglas & Tooker 2015 Figure 4 The increase in neonicotinoid seed treatments in corn and soybeans from 2003-2013. Credit: Dr. Dilip Venugopal; original data from Douglas & Tooker 2015 Beyond the nutritional stress put on pollinators and other fauna by habitat reduction, use of harmful pesticides increased in these expanding, increasingly simplified crop systems. In larger, more simplified cropping systems, pests spread more readily and can exist in higher numbers, so farmers increase their pesticide use. This trend is observable in both corn and soybeans. Use of neonicotinoids, a class of generalist insecticides shown to cause some health issues in bees, has gone up significantly since 2007. However, EPA studies did not find significant benefits from neonicotinoid seed treatments in soybean. Glyphosate (a.k.a. Round Up) use has also increased since 2007, along with genetically engineered crops, such as Bt corn, which is modified to produce a specific pest-targeting toxin. Widespread application of these pest management technologies over larger areas led to the evolution of increased resistance among pest populations. 90% of corn is now Bt, and Bt resistance among the corn rootworm (a common corn pest) is spreading. Decreasing GHG emissions is undoubtedly a critical environmental concern. Dr. Venugopal’s work emphasizes the importance of considering other factors when evaluating the ecological impact of a policy decision, and the need to consider an ecosystems based assessment of environmental impacts. Dr. Venugopal suggests the EPA could move towards a more holistic policy approach, coupling sustainable production practice and land management to limit environmental impacts from biofuel production as required by EISA. About the authors: Kelly Kulhanek is a PhD student in the vanEngelsdorp bee lab. She studies best honey bee management practices and honey bee pest drift across landscapes. Lauren Leffer is a MSc student in the Lamp Lab. She studies wetland/stream connectivity through macroinvertebrate communities on the Delmarva Peninsula. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed