|

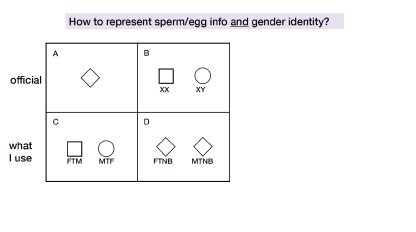

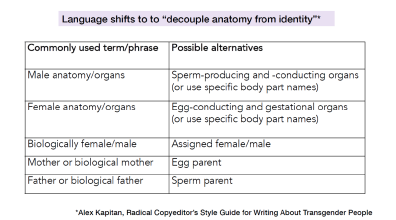

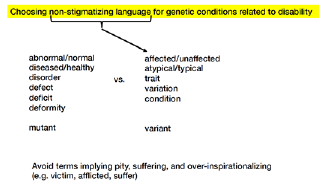

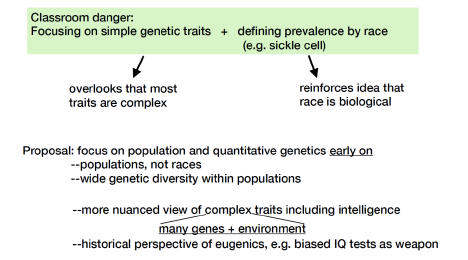

Written by: Mike Nan Dr. Karen Hales is a Biology Professor at Davidson College who employs genetic tools with the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) model to understand the molecular mechanisms of mitochondria function in cells. While past colloquium speakers have presented on the latest research in their lab, Dr. Hales addressed an even more pressing, teaching topic: Enhancing inclusivity in undergraduate science courses through careful wording of course-specific material concerning gender identity, disability, and race. Dr. Hales started her virtual presentation to an audience of 60+ participants with a few broadly applicable approaches to foster a seamless transition to more inclusive pedagogy in undergraduate science courses. These approaches include: (1) eliminate microaggressions (subtle, intentional and/or unintentional behaviors that communicate some sort of bias against underrepresented groups that exacerbate stereotype threat) and increase microaffirmations (small acts of active listening to counteract stereotype threat); (2) highlight research findings from diverse scientists; and (3) accentuate growth mindset (praising and rewarding students’ effort). Ultimately, the goal is to use language frameworks and approaches that help people of all identities feel welcome and supported in the classroom when genetics topics are covered. Undergraduate students usually express more interest in human genetics related to pre-medical studies. However, these topics, if not presented carefully, can result in some students feeling alienated due to the sensitive nature of the information. For example, geneticists frequently use pedigree charts to illustrate and examine inheritance of family traits. The most popular undergraduate genetics textbooks represent females with circles, males with squares, and persons of “unspecified” gender” with diamonds. If the diamond symbol is only used when gender is not explicitly stated, then this implies a male–female binary. Conventional pedigree charts conflate females (circles) as the egg producers and males (squares) as the sperm producers. This convention emphasizes a gender binary and can trigger a type of microaggression, microinvalidations, as that excludes the psychological feelings of transgenders (trans). Trans’ identity and gender does not correspond with the one at birth and most trans are actually not nonbinary, but certain nonbinary people can be trans. Based on the revised pedigree charts in 2008 by the Pedigree Standardization Work Group (PSWG) within the National Society of Genetic Counselors (Bennett et al. 2008), trans is represented by a diamond (Figure 1A), or sometimes by a circle or square corresponding to “gender” combined with the sex chromosome karyotype (identity) at birth (Figure 1B). However, this format in Figure 1A is still potentially offensive and inaccurate to use a diamond to represent gender identity for binary trans. To address this issue, PSWG members have introduced but not standardized another possible format (Figure 1C), which uses a symbol consistent with gender identity, as well as including female to male (FTM) or male to female (MTF) for a binary trans person. This method attempts to be inclusive of same-sex couples as well as diverse gender identities. An additional question is how to represent sperm/egg info and gender identity for trans nonbinary people. For this, Dr. Hales cleverly uses a diamond symbol for nonbinary (NB) people along with the notation of male to nonbinary (MTNB) or female to nonbinary (FTNB) (Figure 1D). Dr. Hales is also explicit with her students about her deliberate deviation from PSWG standards to convey gender identity as central yet separable from the binary of sperm–egg production. Figure 1: Trans is represented by a diamond (A), or by a circle or square corresponding to “gender” combined with the sex chromosome karyotype (identity) at birth (B). PSWG members use a symbol consistent with gender identity, as well as including female to male (FTM) or male to female (MTF) for a binary trans person (C). The speaker uses a diamond symbol for nonbinary (NB) people along with the notation of male to nonbinary (MTNB) or female to nonbinary (FTNB) (D). (image credit: Hales 2020). Dr. Hales encourages more inclusive language to welcome trans students to “decouple anatomy from identity” (Table 1) by eschewing “obligatory gendered assignment of body parts.” For example, instead of using mother, use egg parent as an alternative. She mentions that any dramatic language shifts towards separating anatomy from identity will face difficulty with acceptance in the medical field. However, if biology instructors separate the egg–sperm binary from gendered language to maintain and not invalidate diverse gender identities, then they can help spur this gradual shift Table 1: Suggestions for language to separate body parts, sperm, eggs, and parental relationships from gendered language (image credit: Hales 2020). In her presentation, Dr. Hales also offered suggestions for careful language choices for defining and categorizing human traits to promote a non-stigmatizing classroom environment (Figure 2). Sometimes, textbooks link “trait” with unclearly defined, often-used “condition” and “illness” terms. However, not every difference in a “trait” gives rise to “disease,” especially if “trait” and “disease” are less equivocally defined. To be more inclusive to students with disabilities, more gender-neutral language in the right column of Figure 2 should be used, such as “variant” instead of “mutant” in the left column. Figure 2: Recommendations for promoting inclusivity regarding disability (image credit: Hales 2020). Finally, Dr. Hales, drawing extensively on information from Dr. Brian Donovan and his collaborators, finished her presentation with a discussion of pseudoscientific racism, which is a stereotype threat regarding intelligence, for instance. She noted that the reality is that races are socio-cultural constructs, not biological realities. In biology teaching, there is often an unwarranted focus on simple genetic traits and on defining trait prevalence with respect to “race” (e.g. sickle cell), which overlooks that most traits are complex and reinforces the idea that race is biological (Figure 3). To rectify this misperception, the focus should be on population and quantitative genetics early on and adopting a more nuanced view of complex traits (influenced by many genes and the environment) including intelligence. Furthermore, more diversity and inclusion in clinical trial subjects is necessary and a need to disentangle from the race/population conflation. In clinical trials, race is confounded with biology, race in this context is meant to estimate population diversity or the resulting inequities in health outcomes due to disparities in social and economic statuses among populations. Figure 3: Students’ misperceptions of racial biological differences and advice for rectifying these misperceptions (Donovan 2019; Hales 2020). In sum, language choices and frameworks can help build a more welcoming atmosphere in classroom teaching. Inclusion can provide a hospitable environment not only for persons in the spectrum of trans/nonbinary community or with disabilities, but also cultivate a better sense of belonging among students of various identities who might otherwise feel alienated through increased tolerance and comfort with identity differences, the more identity differences are accepted in the classroom. References

Written by:

Mike Nan is a PhD student in the St. Leger Lab studying how circadian rhythms affect Metarhizium infection of Drosophila. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed