|

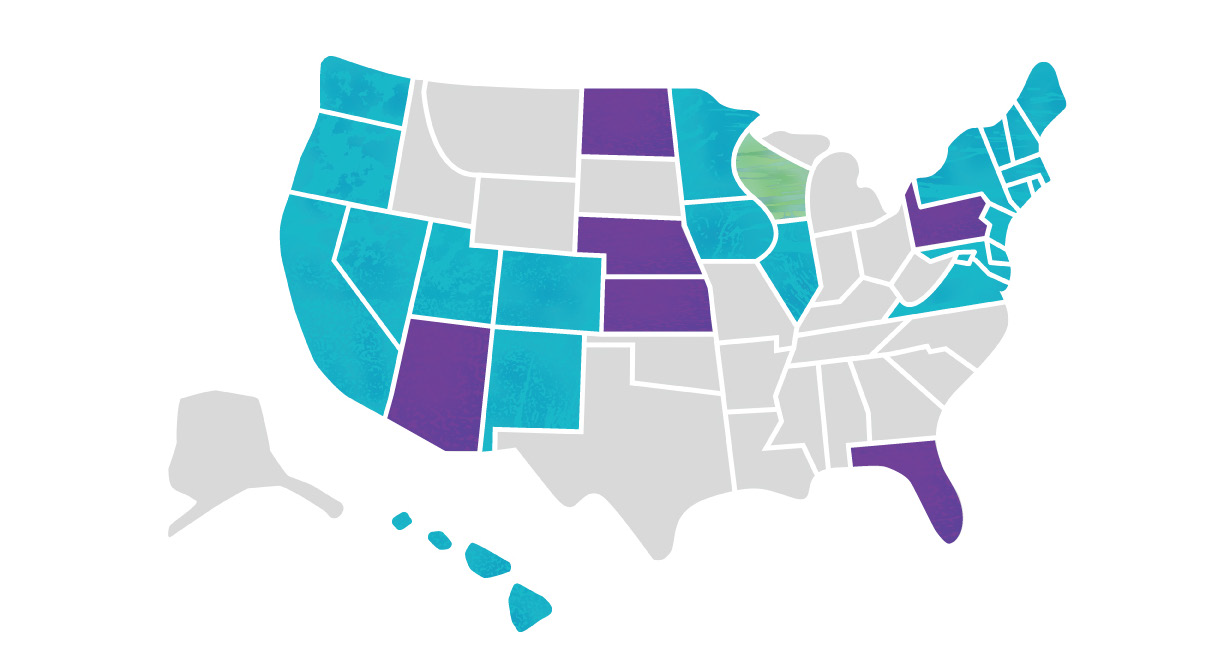

written by: Angela Saenz and Taís Ribeiro Our identity and background shape how we work. This is not different in science. In their seminar for the University of Maryland Entomology department, Dr. Lauren Esposito gave a presentation entitled "Why Entomology Needs Queer Voices", sharing their story and how it has inspired them to work towards increasing diversity and inclusion in STEM. Dr. Esposito, describing themself as an entomologist since childhood, is the Curator and Schlinger Chair of Arachnology at the California Academy of Science. There they have been researching the evolution, systematics, and biogeography of scorpions (Figure 1). Initially a pre-med undergraduate student, they changed their major to entomology once they realized it was an actual career. Not knowing about career paths in STEM is very common among historically oppressed groups like the Hispanic community Dr. Esposito grew up in. Repressed by the Catholic religious beliefs from the Hispanic community where they grew up in, Dr. Esposito felt like an outsider, unable to express their identity. While a graduate student at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, they found themselves, for the first time, in an institution in which the majority was not Hispanic. They then realized the disparity among the members of the scientific community. Diversity and inclusion in STEM Historically, the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) fields have been underrepresented by women and ethnic minorities (Patridge et al., 2014), and sexual and gender minorities have not been any different. Approximately thirty percent of the US population is Black, Latinx, or Native American, but only 17% of this population choose to study and work in STEM fields. These historically underrepresented minorities have 6-year bachelor’s degree completion rates that are 50% lower than their Asian and white peers, and make up only 17% of life sciences undergraduates. Women, disregarding their income levels and SAT scores, still perform worse than their male counterparts, and first-generation college students have the highest drop-out rates. All of these factors add up and serve as symptoms of why minorities have a difficult time entering, staying, and thriving in STEM fields. Dr. Esposito quotes the first ever report from a scientific society about the culture and climate of LGBTQ+ physicists, stating that there is a "Heterosexist climate that reinforces gender role stereotypes in STEM work environments" (Atherton et al. 2016). This could be interpreted as if you are not a cis-gendered heterosexual white male, the work environment in STEM could be problematic for you and your cultural and sexual identity. Another factor to take into consideration is the potential for detrition. Until the historic Supreme Court ruling in 2020, 22 states had no legislation regarding job security related to sexual orientation and gender identity (Figure 2). This enforced and perpetuated a state of constant fear about job security in the LGBTQ+ community so much so that, even still, they may not disclose their own identity. Students who self-identify as trans or gender non-conforming experience the highest rates of on-campus sexual assault and misconduct in universities. In addition, 60% of all students who self-identify as LGBTQ+ have reported at least one incident of sexual misconduct or harassment while undergraduates (Cantor et al., 2015). Queer people are as likely to experience technical or lab as undergraduates, but more likely to switch to a non-STEM (Chang et al., 2014). This in turn, affects the diversity of these fields as well. Even within the workforce in STEM fields, we can see that 40% of people have not revealed their sexual or gender identities to their colleagues, and almost 70% of faculty members who have disclaimed their identity have expressed discomfort in their university department. Up to 20% of the surveyed people have admitted that they have experienced professional devaluation after coming ‘out’ (Patridge et al., 2014).  Figure 2. Non-discrimination in employment in the United States (HRC 2021). Blue: Expressly prohibit employment discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Green: prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation. Purple: Enforcement authorities accept complaints. Grey: no legislation prohibiting discrimination. Working towards change

After experiencing the hardships that the LGBTQ+ community goes through in the STEM field, Dr. Esposito was driven by a need to make things better, to connect with people, and to find a way of improving the lives and experiences of this community. Different efforts have come to life through diversity offices in scientific institutions and colleges, and especially through the efforts of individuals. In order to connect LGBTQ+ scientists together, Dr. Esposito with a team of five other people created the 500 Queer Scientists initiative. This project is dedicated to providing visibility and opportunities to the LGBTQ+ community in STEM through connections and role models of queer scientists. It started with 50 stories of queer scientists, and now, after three years online, the project has more than 1600 contributions! Dr. Esposito also participates in Entomologists of Color, an organization that provides scientific society memberships to People of Color (POC). These memberships allow participation in networking events and different tools necessary for a successful career. The call for action also goes out to people who do not identify themselves as part of a minority. Anybody can be an ally to support oppressed communities by following simple actions. First, to be an ally, you need to educate yourself by searching for information without expecting that underrepresented people have a duty to explain certain issues and topics to you. It is also important to listen to what people have to say, making space and amplifying their voices. We should also normalize the use of pronouns by acknowledging them and, if mistakes are made, just listen, recognize, learn, and move forward without amplifying or fully dismissing a situation. Lastly, and most importantly, allies should make themselves visible by challenging discrimination. During situations in which someone is being discriminatory, an ally can intervene by explaining why that attitude is not correct, or even by changing the subject. An ally can also challenge discrimination without direct confrontation by acting at a later time or by reporting the situation to someone of higher authority. As Dr. Esposito says, "Who you are, what your identity is, it’s what enriches science." Providing a welcoming environment and openly sharing opportunities with underrepresented minorities is the key to better science and innovation. Their talk inspired us to take action by demonstrating that even small groups of people with simple initiatives can have a big impact on making STEM a more diverse, inclusive, and welcoming environment. References Atherton, T. J.; Barthelemy, R. S. ; Deconinck, W., Falk, M. L.; Garmon, S.; Long, E.; Plisch, M.; Simmons, E. H.; Reeves, K. (2016) LGBT Climate in Physics: Building an Inclusive Community American Physical Society. 118-126. Cantor, D.; Fisher, B.; Chibnall, S. H.; Townsend, R.; Lee, H.; Thomas, G.; Townsend, R.; Westat, Inc. (2015). Report on the AAU campus climate survey on sexual assault and sexual misconduct. Association of American Universities. https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/AAU-Files/Key-Issues/Campus-Safety/AAU-Campus-Climate-Survey-FINAL-10-20-17.pdf Chang, M. J., Sharkness, J., Hurtado, S., & Newman, C. B. (2014). What matters in college for retaining aspiring scientists and engineers from underrepresented racial groups. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 51(5), 555-580. Hughes, B. E. (2018) Coming out in STEM: Factors affecting retention of sexual minority STEM students. Science Advances, 4:3, eaao6373, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aao6373 Patridge, E. V., Barthelemy, R. S.; Rankin, S. R. (2014) Factors Impacting the Academic Climate for LGBQ STEM Faculty. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 20:1, 75–98, DOI: 10.1615/JWomenMinorScienEng.2014007429 Authors Angela Saenz is a second-year Master’s student in the Gruner Lab studying the spatial and temporal distribution of natural enemies of the Emerald Ash Borer in Maryland. Taís Ribeiro is a Ph.D. student in the EspindoLab studying the ecology and evolution of South American oil-collecting bees from the genus Chalepogenus. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed