|

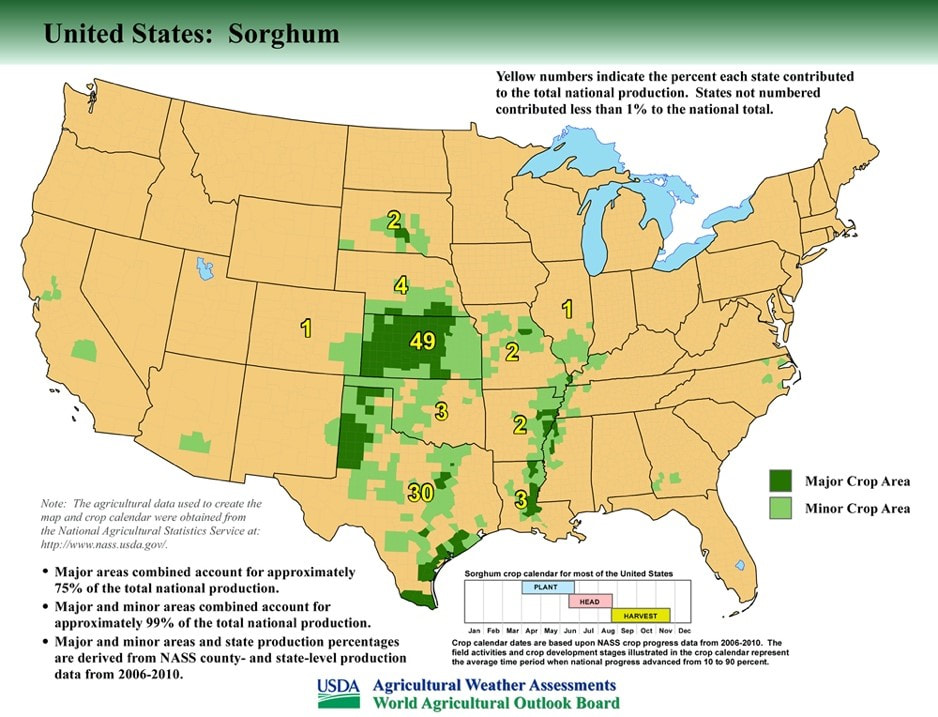

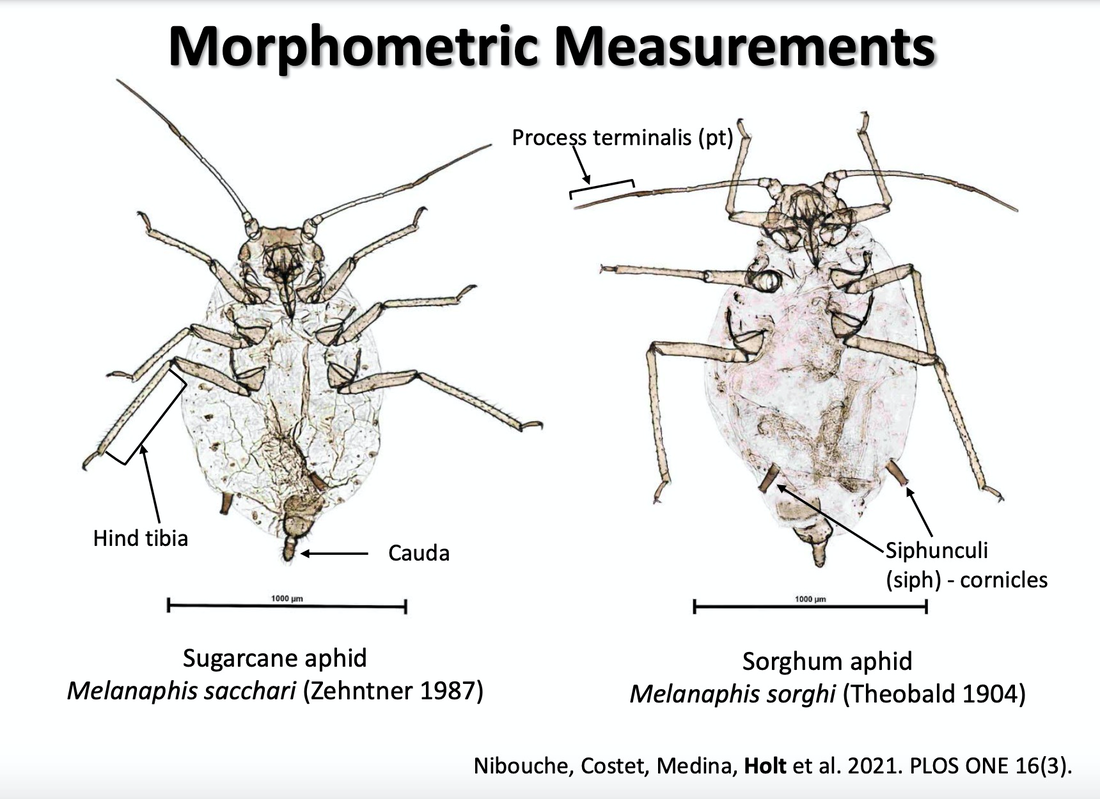

written by: Minh Le Not many people have heard of the sorghum plant, so you might be surprised to know that it is grown in 21 states (Figure 1)! The “Sorghum Belt”, or area comprising states that have abundant sorghum production, stretches from South Dakota all the way down to southern Texas (National Sorghum Producers). The sorghum plant produces nutritious grain, which is an important ingredient for livestock feeds as well as a whole grain alternative to people with low gluten tolerance or who suffer from celiac disease. Besides its nutritional benefits, sorghum production can have a positive impact on the environment and sustainability efforts, as the sorghum bushels can be extracted for ethanol, a renewable source of fuel, and require one-third less water to grow compared to other feedstocks (National Sorghum Producers). Despite its agricultural and environmental importance, as with other widely cultivated agricultural crops, these plants are a buffet for pest insects whose voracious appetite cause significant economic damage every year. A prominent invasive pest feeding on sorghum in the US is the sorghum aphid (Melanaphis sorghi). These insects use their syringe-like mouthparts to pierce and suck juices from plant tissues, damaging them. In 2013 and 2014, it is estimated that these aphids caused 50 to 100% of crop loss, and in 2015, sorghum producers in the Rio Grande Valley lost approximately 31 million dollars. The entomology colloquium welcomes Dr. Jocelyn Holt, a researcher at Rice University, Texas, who provided insight into her research on the population genetics of sorghum aphids across the US and the symbiotic microbiota that is associated with them. An invasive organism is an introduced, non-native organism that has expanded its population size beyond the site of its initial introduction and is causing harm to the environment, economy, and/or human health [1]. The sorghum aphid began to spread in 2013, originating from Texas, and by 2018, had spread throughout all of sorghum growing states. Historically, the sorghum aphids have been considered as the same species as the very similar sugarcane aphid (Melanaphis sacchari), which was introduced to Florida in 1977 and is an invasive pest that feeds on sugarcane. During the initial pest outbreak it was thought that the sorghum aphid was derived from a population of sugarcane aphid which experienced a host shift, a phenomenon in which a pathogen or pest changes their host; in this case, it means that a population of sugarcane aphids changed their food preference from sugarcane to sorghum. However, Dr. Holt casted doubts on this prevailing paradigm, and hypothesized that the sorghum aphid is actually a cryptic species, a species which is very hard to distinguish from another species, and is separate from the sugarcane aphid. In this light, the sorghum aphid was newly introduced in 2013 from a different location, instead of originating from the already-established sugarcane aphid. To test this hypothesis, Dr. Holt and her colleagues collected aphid samples on sugarcane and sorghum throughout the world and compared them to each other, looking at four external anatomical structures (Figure 2). The result shows that there are indeed subtle differences in these structures between aphids collected from sugarcane vs sorghum, suggesting that they are two different species [2]. In addition to that, they examined a gene called EF1-alpha, and determined that there is a difference in a single letter in the genetic code between the two aphid types [3], further supporting the result derived from previous anatomical observation. Finally, she examined the composition of microbes living inside these two types of aphids and discovered that there are also differences between aphids collected on sugarcane vs sorghum [4]. This difference makes sense, as these microbes help with the aphid’s nutritional intake, so feeding on a different host plant is often correlated with having a different microbiota composition. To summarize, the sugarcane aphid and the sorghum aphid represent two different species, instead of one species with a different host preference. The next question that Dr. Holt asked is whether there is genetic diversity between different sorghum aphid populations across different states. To answer this question, she collected 55 aphids from different host plants across five different states: Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, with the majority of samples (46) from Texas. After the collection, she extracted their DNA and sequenced them in order to give insight into their genetic differentiation. The results show that the genetic compositions of sorghum aphids are different across states. Although, some sorghum aphids collected in Texas and Louisiana share a large degree of similarity in genetic composition. There is also a degree of genetic differentiation among aphids within Texas as well. In short, Dr. Holt demonstrates that the populations of sorghum aphids across the US are genetically diverse.

Finally, Dr. Holt is currently characterizing the properties of the sorghum aphid’s honeydew. Honeydew is the sticky and sugary liquid excreted by aphids while they are feeding on the plant host. Honeydew excreted by the aphid attracts ants, which in turn facilitates a mutualistic relationship between these insects [5]; the ants get to feed on the sugary honeydew, whereas the aphids get protection from predators. Dr. Holt has shown that there are little differences between the microbiota of honeydews excreted by aphids feeding on sorghum vs Johnson grass. However, the microbial composition inside of sorghum aphids’ honeydew changes over time, and there are major differences between the honeydew microbiota and the aphid’s internal microbiota. In summary, the microbiota residing in sorghum aphid’s honeydew is dynamic, and understanding it will help elucidate how sorghum aphids form symbiotic relationship with other organisms, such as the tawny crazy ants, and in turn, can help us develop more targeted pest management practices. By studying the genetic composition of sorghum aphids and the microbes that are associated with them, Dr. Holt has made valuable contributions toward finding an effective strategy to control these invasive pests on grain sorghum. In addition, her future projects include further analysis into the microbial composition of the tawny crazy ants, associations of ants with aphids, and whether herbivores impact commercial vs heirloom sorghum differently. To learn more about Dr. Holt, her colleagues, and her research, you can visit her website. References: [1] Bernaola, Lina and Jocelyn R. Holt. Incorporating sustainable and technological approaches in pest management of invasive arthropod species. Annals of the Entomological Society of America vol. 114,6. 20 October 2021. [2] Nibouche, Samuel et al. “Morphometric and molecular discrimination of the sugarcane aphid, Melanaphis sacchari, (Zehntner, 1897) and the sorghum aphid Melanaphis sorghi (Theobald, 1904).” PloS one vol. 16,3 e0241881. 25 Mar. 2021. [3] Nibouche, Samuel et al. “Invasion of sorghum in the Americas by a new sugarcane aphid (Melanaphis sacchari) superclone.” PloS one vol. 13,4 e0196124. 25 Apr. 2018. [4] Holt, Jocelyn R. et al. “Differences in microbiota between two multilocus lineages of the sugarcane aphid (Melanaphis sacchari) in the continental United States.” Annals of the Entomological Society of America vol. 113,4. July. 2020. [5] Holt, Jocelyn R. et al. Quantifying the impacts of symbiotic interactions between two invasive species: the tawny crazy ant (Nylanderia fulva) tending the sorghum aphid (Melanaphis sorghi). In Review. Author: Minh Le is a PhD student in the Pick Lab studying gene regulation during insect development. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed