|

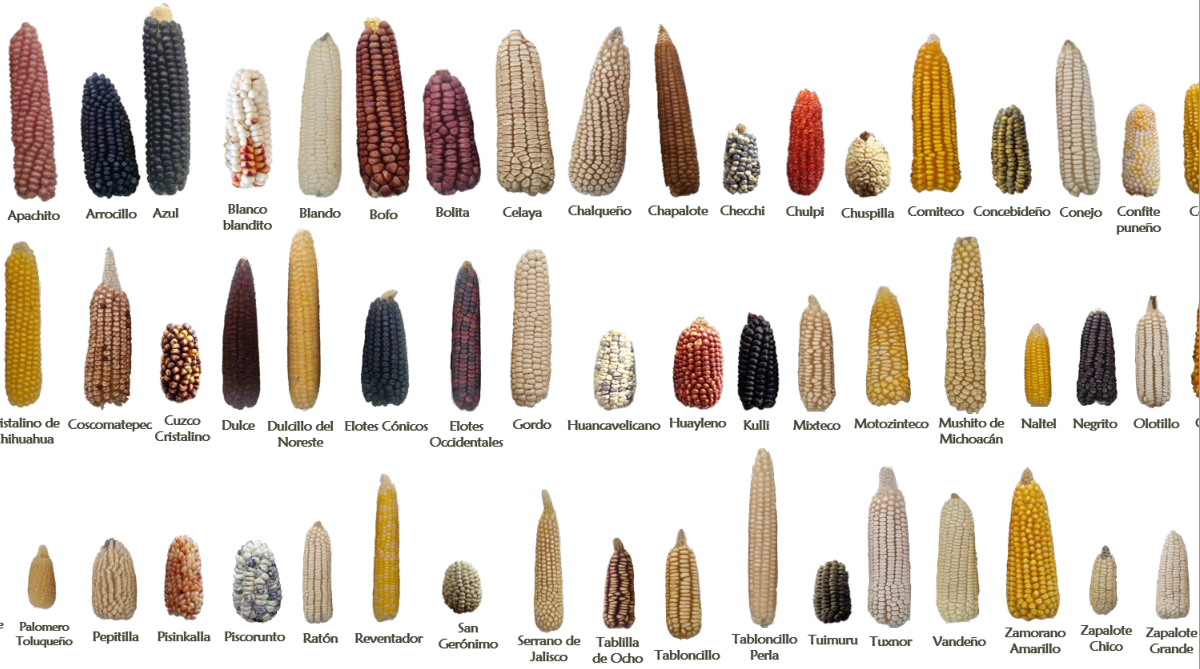

written by: Alireza Shokoohi What are you passionate about? Dr. Carlos Blanco may be a Senior Entomologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, handling the international import and domestic movement of insects, but he still spends much of his own time conducting research. Early in the mornings and on weekends, he can be found in crop fields collecting data to answer questions about a subject he is passionate about: corn. Corn may be the single most impactful crop grown in the world. While it doesn’t yet rival other grains such as rice or wheat in terms of direct consumption, its popularity is growing. It produces greater yield given an equal amount of seed planted and is used for numerous other purposes such as feed for livestock and even biofuel. However, there’s another reason Dr. Blanco is so interested in corn, and that is its connection to his home country of Mexico. Perhaps due to its origins in the southern part of the country, where it is believed to have first been domesticated from native teosinte plants, corn has a massive cultural significance to the people of Mexico. Due in part to this reverence, there are major differences between corn growing practices in the U.S. and in Mexico, and perhaps the largest factor is the prevalence of hybrid and genetically modified corn. Mexico’s government has a long history of opposition towards genetically engineered corn, also known as “biotech” or “GM”. These varieties of corn were introduced in the tail end of the 20th century and have been genetically altered to make them more favorable for growth through different means, including increased resistance to herbicides, pests, and other dangers, resulting in higher yields and lower growing and management costs. Despite these benefits, many in Mexico have their concerns. In recent years, the topic has become one of much political debate, with opponents of biotech corn citing preservation of indigenous landraces (unique corn varieties that have been cultivated for generations), environmental and food safety issues, and potential cultural and political conflicts as reasons to maintain the ban on GM corn. This is why it was such a shock when five years after the introduction of GM corn, researchers found that biotech DNA promoters were present in Mexican corn. Many took this as evidence that transgenes from GM corn were getting into Mexican landraces. But what does this really mean? The presence of these promoters alone doesn’t tell us much, since these promoters could have come from a number of different sources, not all of which are biotech corn. Furthermore, there’s no guarantee that they are functional, and there’s no indication of how frequently they appear in the population. So, Dr. Blanco and his fellow researchers set out to find answers. To do this, they gathered over 120 seed samples from vendors and growers throughout different parts of Mexico, planted the seed samples, and applied herbicides to test the functionality of genetically engineered genes. Dr. Blanco and his colleagues found that a majority of their samples had at least one plant with herbicide resistance, and since there are no natural developments of herbicide resistance in corn, this confirmed that genetically engineered genes granting herbicide resistance are functional in Mexican corn landraces.

But how is this happening? The first culprit is pollen drift - corn is wind-pollinated, meaning it relies on the wind to carry pollen from one plant to another. Pollen from GM plants fertilizing non-GM plants could create hybrids with GM properties. However, Dr. Blanco argues, there’s a limit to how far this pollen travels, and given the distance between the southernmost biotech corn field in Texas and the northernmost location in Mexico where herbicide-resistant corn was found, it would have taken many centuries for pollen drift alone to cause this. Additionally, the overlap in time when these different varieties of corn plants are producing and accepting pollen is very short, making it even more unlikely that pollen drift is to blame. Thus, attention turns to commerce. Dr. Blanco started to test this by performing bioassays on hybrid seed that is commercially available in Mexico but found that none of the plants tested survived being sprayed with the herbicide, meaning these transgenes are not present and functional in seeds from the industry. Next, Dr. Blanco thought about the local seed trade. It’s well-known that Mexican corn growers do not hesitate to share and trade seeds with neighbors, both near and far, as corn crossed with other more distantly related corn tends to be more resilient and produce higher yield. This, combined with the fact that laws prohibiting the growing of transgenic corn in the country are not always adhered to, proves a stronger hypothesis for the spreading of transgenes across the country. So what does this mean for the country? Dr. Blanco argues that this is evidence that the spread of transgenes in corn is inevitable, but also that this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Researchers have detected transgenes in 25% of corn in South Africa, where they have no ban on GM corn, 34% in Brazil after a 12-year ban, and 35% of corn in Mexico after a 25-year persistent ban on GM corn. After conceding to law-violating farmers and lifting their ban on GM corn, Brazil grew to be one of the leading producers of biotech corn, and Brazilian landraces continue to persist. Also in response to the idea that GM corn will outcompete Mexican landraces, he points to the U.S. as an example in which GM corn makes up more than 90% of corn planted, and yet unique varieties of corn still exist and are planted. Dr. Blanco believes that this would be even more the case in Mexico, where landraces are treasured by the Mexican population, who have been incorporating genes from commercial hybrid varieties of corn for more than five decades while allowing landraces to persist. Finally, the growing prevalence of transgenes that confer resistance to obstacles such as drought and pests could provide direct benefits to Mexican farmers. GM corn commonly is engineered to be resistant to caterpillar pests such as fall armyworm, and resistances to this pest would be hugely beneficial to poor farmers who cannot afford pesticides to control the pest. Despite being among the world’s top producers of corn, Mexico also imports a great deal of corn, much of it from the U.S. This shows that the country has a strong appetite for corn, but despite having the capability to produce more, the government has persistently ignored arguments in favor of lifting the ban. Dr. Blanco’s determined research provides much-needed insight into the facts of the matter and will hopefully serve as a source of knowledge for policymakers to make better, more informed decisions in the future. Author: Alireza Shokoohi is a M.S. student in the Lamp Lab at the University of Maryland currently studying ground beetle ecology within agricultural drainage ditch ecosystems. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed