|

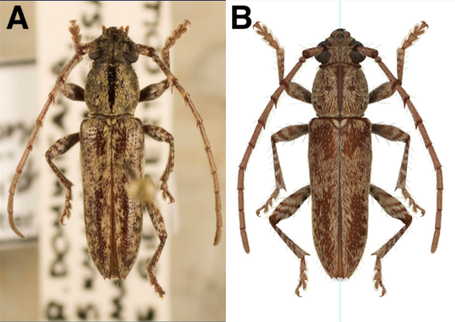

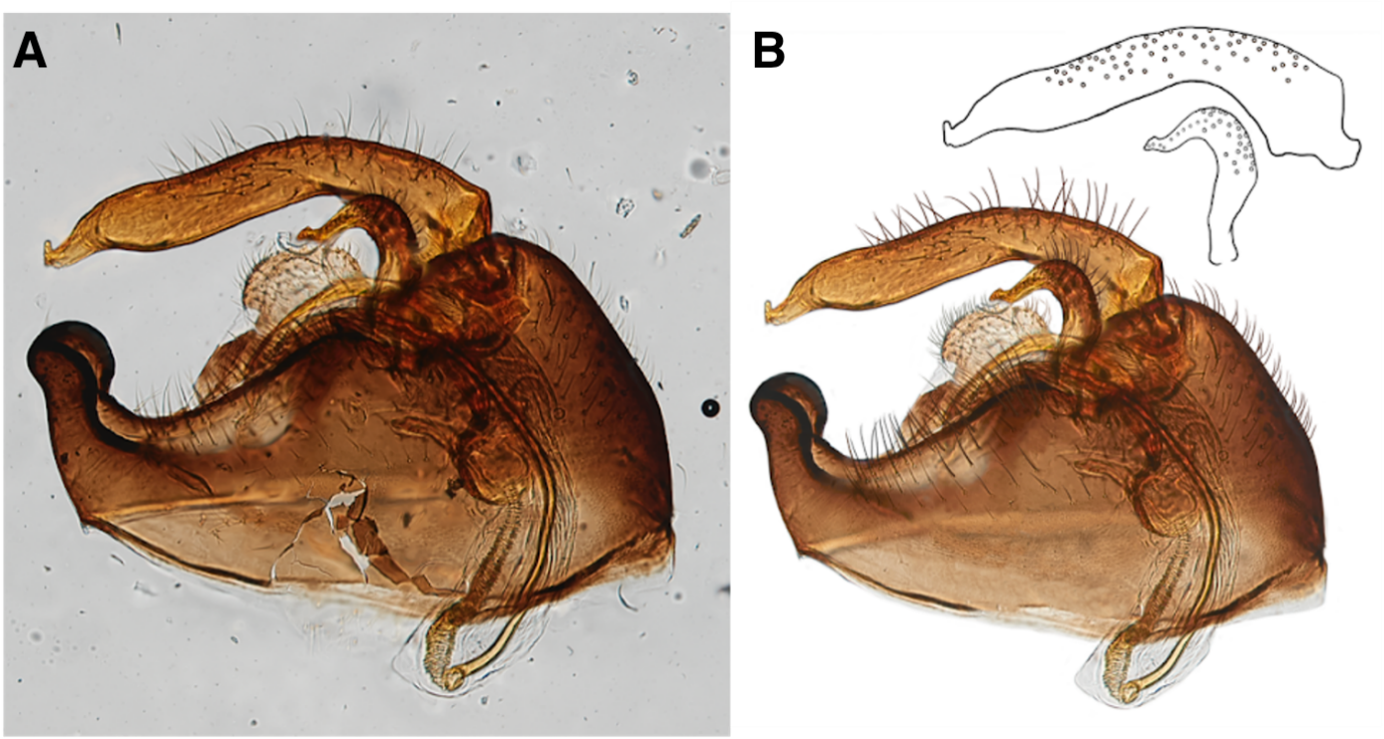

written by: Ebony Argaez and Minh Le The natural world is teeming with gorgeous and awe-inspiring biological structures, patterns, and colors that cannot be described via mere words alone. During the digital age, accurate and realistic imagery of these specimens can be obtained through the lens of a camera. However, the camera can only capture what is, not what could have been. Exquisite imagery requires the gentle and imaginative hand of an artist like Taina R. Litwak a scientific illustrator with the US Department of Agriculture’s Systematic Entomology Lab and the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of Natural History who joins this week’s entomology colloquium at the University of Maryland to talk about entomological art in the digital age.  Figure 1: A photographic image of a longhorned beetle (Elaphidion costipenne) specimen (left) and Litwak's illustration depiction (right). (Image Credit: Taina Litwak) Figure 1: A photographic image of a longhorned beetle (Elaphidion costipenne) specimen (left) and Litwak's illustration depiction (right). (Image Credit: Taina Litwak) Before using illustration and graphics software like Photoshop, her work was done with brush and ink. Litwak’s primary way to illustrate digitally involves two monitors, a scanner, a pressure sensitive drawing tablet and Photoshop, a digital art program. Instead of scanning a piece that was made with brush and ink pen, now a sketch is scanned and final art is produced with a drawing tablet. There are many different resources and tools used to make sure the image that is drawn is represented correctly. Litwak usually starts an illustration with a drawing or series of drawings done with a microscope and camera lucida. She uses often photographs to fill in detail.  Figure 2: Litwak's illustration of a wasp (Humboldteria davidsmithi) preparing to take off. (Image Credit: Taina Litwak) Figure 2: Litwak's illustration of a wasp (Humboldteria davidsmithi) preparing to take off. (Image Credit: Taina Litwak) One useful tool is the scanning electron microscope (SEM). SEM is a microscope that uses an electron beam in replacement of a light source. The electrons interact with the sample to produce signals that reveal the sample’s composition, providing resolutions between 1 micron (μm) to 1 nanometer (nm) and provides a 3D image of things that are of higher magnification. [1] SEM images are used to get an accurate view of an insect’s different body parts and parts that are not visible to the naked eye. Another tool that is used for photography involves taking pictures using a stacking technique, where you take 2-100 images, with each image having a different focus level and using specially designed software to combine them to make one high resolution image. An example of this is the Helicon Focus program. With these tools in hand, Litwak is able to construct an accurate depiction of an insect (Figure 1B) from a curated specimen (Figure 1A). As for the significance of Litwak’s work, you might ask why would a hand-drawn illustration be preferable and perhaps even necessary, over the more perfect and detailed photographic image of the actual specimen? The answer to this question is simply imagination, which can be elaborated and exemplified in three different ways. Firstly, Litwak is able to create an imaginative picture mirroring the elusive natural world in which a certain structure or phenomenon is rare or simply unobservable. For example, Litwak was able to breathe life into an image of a wasp (Humboldteria davidsmithi) getting ready to take off (Figure 2), a phenomenon that is too transient for a snapshot of normal photography to capture, constructing the morphology of the wasp from dead specimens alone. Secondly, there are many times in which biological specimens are not perfectly preserved and parts can go missing or are broken. As a scientific illustrator, Litwak is able to “repair” this imperfection on a two-dimensional screen, as exemplified in Figure 3, where she was able to transform a slightly broken hemipteran genitalia (Figure 3A; photography) into a perfect version of this structure (Figure 3B; Litwak’s illustration). Finally, in order to highlight certain details of a biological structure for more insight, she is able to “dissect” the specimen on a two-dimensional screen, without jeopardizing the integrity of the real specimen she’s illustrating. For instance, in addition to repairing the specimen, Litwak isolated two slightly obscured structures of the hemipteran genitalia out against the backdrop, rendering them more visible (Figure 3, top right corner). Before focusing on illustrating insects, Litwak brought her artistic expression and passion to a variety of natural scientific fields. She has provided illustrations in botany, vertebrate biology, including birds, fishes, and human anatomical structures, then down to the molecular level with tissue- and cellular-level processes, and finally breaking the stratosphere into astronomy.

It is important to note that a scientific illustrator is not just an artist, but also a scientist at heart. It takes scientist to accurately recreate an organism’s morphology on a canvas, reflecting the reference specimen, but it takes an artist to make this motionless and quiescent depiction come to life. Take for example, in Figure 2, Litwak has to have a fundamental understanding of how a wasp would realistically position itself pre-takeoff, in order to construct this piece of illustration. Litwak’s work mainly focuses on entomological art but there are other scientific illustration specializations that are available and is able to provide other illustrations based on the needs of clients. Depending on the magazine, journal, researcher, or textbook publisher they use scientific illustrators to inform and communicate scientific ideas, topics and subjects as accurately as possible. It makes the subject engaging and accessible to different people. To learn more about Litwak and see more of her paintings you can visit her website litwakillustration.com. Reference: [1] Vernon-Parry, K. D. “Scanning Electron Microscopy: An Introduction.” III-Vs Review, vol. 13, no. 4, July 2000, pp. 40–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0961-1290(00)80006-X. Authors: Ebony Argaez is a MS student in the Pick Lab studying the effectiveness of RNAi in diverse insects. Twitter: @em_argaez Minh Le is a PhD student in the Pick Lab studying gene regulation during insect development. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed