|

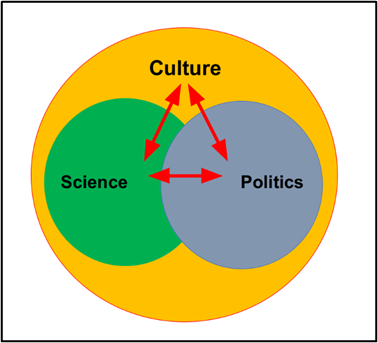

written by: Amanda Rae Brucchieri and Robert Joseph Salerno "The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it.” -Neil deGrasse Tyson. Can this quote be contested? To answer this question, one must consider the way scientific knowledge is continually evolving. The scientific process is self-correcting, meaning the acceptance of ideas should be based on available data. What is often overlooked are the influences of politics, policy, culture, and community in the process of science and the acceptance of scientific data. Dr. Fred Gould, a distinguished professor of Entomology at North Carolina State University whose relationship with the University of Maryland extends back over 30 years, addressed a full hall about this shadowed intersection of science and society. In his talk, Gould dove into the 16-year ban of Mendelian genetics in the Soviet Union and the history that resulted in the ban’s conception.  Figure 1- Sculpture of Stalin and Lysenko, Stalin held a branching wheat head in his hand (Borinskaya SA, Ermolaev AI, Kolchinsky EI, 2019). Figure 1- Sculpture of Stalin and Lysenko, Stalin held a branching wheat head in his hand (Borinskaya SA, Ermolaev AI, Kolchinsky EI, 2019). The ban of Mendelian genetics coincided with conflicts involving scientists Nikolai Vavilov and Trofim Lysenko, and the Soviet government. Vavilov was a pioneer in applied evolutionary biology who traveled around the world studying Mendelian inheritance of crop traits. His research resulted in the theory of 8 centers of crop origin and was used to create the germplasm bank system which serves as a genetic archive for crop varietals and their tissues (Vavilov, Nikolai I, 1926). His work was highly influential and supported until Lysenko, another agronomist, brought forth his ideas, that directly opposed Vavilov. Lysenko’s vernalization ideology stated that the heredity of plants could be influenced by “educating” them (Borinskaya SA, Ermolaev AI, Kolchinsky EI, 2019). The vernalization technique involved taking the seeds of winter crop varieties that perished from harsh frosts and exposing them to low temperatures before planting them in the spring as they would with normal spring varieties. This technique shortened the plant’s vegetative period and sometimes led to ripening in cold climates. Lysenko connected this occasional result with heritable changes caused by vernalization and promised that continued “education” of these crops would result in higher yields (Borinskaya SA, Ermolaev AI, Kolchinsky EI, 2019). Although geneticists knew this to be false, this vernalization ideology was supported by the Soviet government and persisted from 1948 to 1964. During this time, the Soviet working class was experiencing severe famine due to low crop yields and stagnation of agricultural productivity. The Soviet government was searching for a solution when Lysenko promised he could develop crops to meet their nutritional and satiation needs in a fifth of the time Vavilov could. This promise gained Lysenko many supporters, but he was also favored due to his proletariat or working-class background. He embodied the dream of a working-class Russian. A dream that someone who has no power or influence (working-class) could, one day, become a wealthy and powerful influencer. Vavilov on the other hand, was brought up around greater affluence and the science he studied was considered something that the bourgeoisie (upper classes) practiced, resulting in a cultural divide between he and the working class of Russia. With public support, Lysenko was viewed as an excellent spokesperson for the Russian government and proved to be invaluable in spreading Soviet influence. Leaders bolstered him and were known to provide input and even directly edit his speeches. It is unclear whether any of this input was supported by scientific data, but Lysenko’s speeches would reinforce the political agenda of those in power. The ban of Mendelian genetics in the Soviet Union was also influenced by the eugenics movement in the United States and other regions of western Europe. Genetic predeterminism, the backbone of the eugenics movement, was the idea that the fate or destiny of an individual is determined by their genes and was therefore unmalleable. This idea, which was based on scientific understanding of Mendelian genetics at that time, was contrary to the communist ideals which were supported by the Soviet Government. Today, scientists understand that the principles of Mendelian genetics underlie inheritance of organismal traits. However, we now understand the critical role that the environment plays in shaping complex organismal traits, including human behaviors. Throughout the time prior to and during the ban of Mendelian genetics, however, strong cultural and political forces created a dichotomous view of the impact of genes and environment on organismal traits, which led to rejection of Mendelian genetics in the Soviet Union.  As the talk concluded, Dr. Gould, having laid this history at the feet of his listeners, posed two questions: “What would it take for you to reject Lysenko?” and “How does your science fit into the relationship of science, culture and politics?” Only now do we see how politics and culture likely led to the rise of support for eugenics in the U.S and Western Europe, as well as the Russian conflict of Vavilov and Lysenko. As scientists, we need to be aware of what influences our values and our work. “Ideology can slant our views dramatically,” Gould said to explain why we should not look at history with the opinion that they should have known better. Hindsight allows us to see how these things happen, when science is swept up in the motives of man. In the discussion that followed the seminar we spoke about the impact of society on today's science “trends” and how the availability of funding mixed with the desire to advance one’s field of research can lead to the spread of misinformation or misrepresentation. It can lead to promises that go unfulfilled. As most in the room were budding scientists, we looked to our guest speaker for some advice on how to tread the boundaries of culture, science, politics and socioeconomics. As a strong influence and supporter of interdisciplinary collaboration, Dr. Gould spotlighted the importance of “reserving judgment and opening your mind”. This is crucial because, as we said before, the science of today is not always the science of tomorrow. Citations: Vavliov, Nikolai I. “Tzentry proiskhozhdeniya kulturnykh rastenii.” [The Centers of Origin of Cultivated Plants]. Works of Applied Botany and Plant Breeding 16 (1926): 1-248. Borinskaya SA, Ermolaev AI, Kolchinsky EI. Lysenkoism Against Genetics: The Meeting of the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences of August 1948, Its Background, Causes, and Aftermath. Genetics. 2019 May;212(1):1-12. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.301413. PMID: 31053614; PMCID: PMC6499510. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed