|

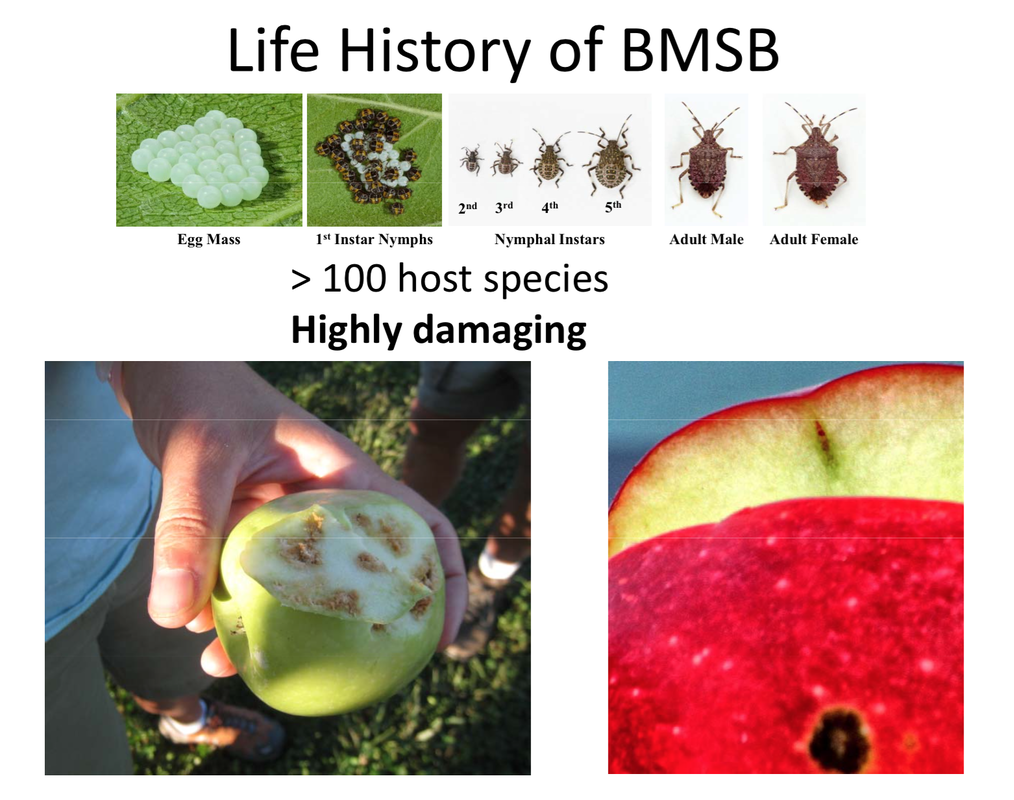

In his experiments, Rob uses a synergistic combination of BMSB aggregation pheromone (Khrimian et al., 2014) and methyl (E,E,Z)-2,4,6-decatrienoate (MDT) (Weber et al., 2014) to lure BMSB into his traps. The advantage of this technique lies in its specificity for BMSB. By using the male-produced aggregation pheromone, Dr. Morrison and his colleagues are able to selectively attract and kill the BMSB without catching other insects (such as bees present in those same orchards) in the crossfire. Since this method only targets the BMSB, the ecosystem will remain largely uninterrupted, allowing for seamless integration of these traps without fear of large-scale ecosystem repercussions. The availability of these attractants in conjunction with research looking into convenient trap designs for growers means that these strategies have real field potential. Tired of blanketing your entire orchard with gallons of pesticides in order to combat the stink bug menace? Imagine drawing the bugs to a smaller spray area in order to deliver them to an untimely, yet well deserved, end while reducing your environmental impact. Dr. Rob Morrison at the USDA definitely thinks this is possible! The brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys, aka BMSB) is an invasive pest originating in China. Since its appearance was first noted in Pennsylvania, the stink bug has spread throughout much of the United States (Wallner et al., 2014), as well as parts of southern Canada, with the highest numbers and largest impact seen in the eastern US (http://www.stopbmsb.org/where-is-bmsb/). Adult BMSB are known to overwinter in shelters as well as homes, increasing their chances of survival during the cold winter months (Lee et al. 2014). BMSB are known to feed on orchard crops, ornamentals, small fruits, vegetables, as well as field crops and can cause extensive damage in relatively short amounts of time. Due to this, methods for controlling BMSB are in high demand. Dr. Morrison believes we can use what is referred to as the ‘Attract-and-Kill’ strategy (http://www.stopbmsb.org/managing-bmsb/attract-and-kill/), in which BMSB attractants are used to lure them to a location of a person’s choosing, in order to target pesticide applications to dispose of them. He is currently testing variants of this technique to determine which type of traps and which amounts of insecticide generate the most efficient BMSB mortality levels. He has shown that the attractants keep the bugs within a very small area of arrestment even with low concentrations of the stimuli (about 2.5 meters). Additionally, these attractants can arrest the insects for at least a day. This provides growers with time to react to their presence and time for the stink bug to ingest a lethal dose of insecticide. Therefore, you can achieve a high kill rate throughout the season while minimizing damage on adjacent trees. In an analogous situation, trap cropping is being investigated in organic vegetable farms as a means for retaining the stink bugs outside of the crop, and results show there is some potential for adapting this strategy to a wide range of systems.  Figure 3. Predators of BMSB eggs. From top to bottom: Ground beetle, earwig, katydid, grasshopper, jumping spider Figure 3. Predators of BMSB eggs. From top to bottom: Ground beetle, earwig, katydid, grasshopper, jumping spider One of many reasons why we should be conscious of our pesticide output is because we are not only killing BMSB with these pesticides, but also many of the naturally occurring enemies that help us in the fight to end the stink bug menace. Researchers are currently focusing on egg parasitoids, tiny wasps which lay their eggs in the eggs of the stink bug, but predators also play a role in reducing BMSB numbers and will feed both directly on the egg masses as well as on nymphs and adults (http://www.northeastipm.org/work_bmsb_files/13-Natural-Enemies-of-the-Brown-Marmorated-Stink-Bug.pdf). Dr. Morrison believes we are actually underestimating the predation rates of BMSB eggs and demonstrated that an unlikely cast of characters may be playing a big role in killing the stink bugs before they even have time to hatch. Beetles, earwigs, katydids, and even jumping spiders find a BMSB egg mass to be a tasty treat. Dr. Morrison’s work with the USDA on reducing pesticide usage (while providing growers with easy-to-use alternatives) is a great example of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) at work. We need as many tools in the IPM toolkit as possible to combat a pest, allowing us to reduce our reliance on pesticides. Citations: Khrimian, Ashot, Aijun Zhang, Donald C. Weber, Hsiao-Yung Ho, Jeffrey R. Aldrich, Karl E. Vermillion, Maxime A. Siegler, Shyam Shirali, Filadelfo Guzman, and Tracy C. Leskey. "Discovery of the Aggregation Pheromone of the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (Halyomorpha Halys) through the Creation of Stereoisomeric Libraries of 1-Bisabolen-3-ols." Journal of Natural Products 77.7 (2014): 1708-717. http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/np5003753. Lee D-H, Cullum JP, Anderson JL, Daugherty JL, Beckett LM, Leskey TC. “Characterization of Overwintering Sites of the Invasive Brown Marmorated Stink Bug in Natural Landscapes Using Human Surveyors and Detector Canines.” PLoS ONE (2014) 9(4): e91575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091575 Weber DC, Leskey TC, Walsh GC, Khrimian A. “Synergy of aggregation pheromone with methyl (E,E,Z) -2,4,6-decatrienoate in attraction of Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae).” J Econ Entomol.(2014);107(3):1061-8. Wallner AM, Hamilton GC, Nielsen AL, Hahn N, Green EJ, Rodriguez-Saona CR. “Landscape Factors Facilitating the Invasive Dynamics and Distribution of the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug, Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae), after Arrival in the United States.” PLoS ONE (2014) 9(5): e95691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095691 Markus Brown is a PhD student studying mycology and behavioral genetics in the laboratory of Dr. Raymond St. Leger. His current research interests include the use of entomopathogenic fungi in insect pest control as well as using Drosophila melanogaster for modeling emotional behavior.

Chris Taylor is a PhD student with focal areas in IPM and insect-microbe symbioses. He studies the brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB), and the focus of his research is on understanding the relationship between BMSB and its gut symbionts to determine whether exploiting this relationship is feasible in management programs Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed