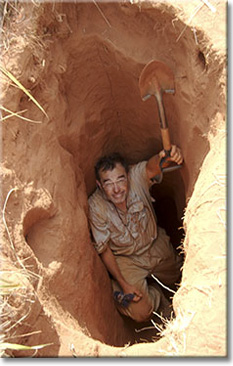

“Symbiotic Evolution and Species Discovery in Fungus-Farming Ants” Dr. Ted Schultz has trekked the Americas in search of precious buried treasure; fungus-farming ants. Although these anthropomorphic creatures are not typically what we consider to be of monetary importance, they reveal a wealth of information about coevolution and symbiotic relationships. Fungus farming ants, like human farmers, cultivate their own food in gardens that are remarkably well cared for (Schultz, et al. 2015). However, unlike humans, fungus-farming ants have an obligate mutualism with their species-specific fungus. Imagine if we could only cultivate one type of food and that food could only survive via human agriculture. Dinner as we know it would be an entirely different experience. Tracking these ants to their colony requires patience and dedication. To start, Dr. Shultz baits the ants with Cream of Rice and waits for an ant of interest to approach and take a bit of bait to bring back to the colony. Using a white food source makes it easier to spot the ants as they travel through the leaf litter, but it is still a difficult task. Once the ant leads him to a colony entrance, the digging starts. Fungus-farming ant colonies may be over 3 meters deep and digging requires several determined entomologists. Walls that cave in and sandy soils are no deterrents when the prize is a sample of the fungus garden and the ants that tend to it.

A. megacephala was first discovered from four specimens individually collected in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Upon closer observation, it was determined that this relic species of ant had more ancestral traits than 15-20 million year old fossil specimens of the same genus. After a few failed attempts to locate a colony of A. megacephala, one was discovered in 2009 by a University of Maryland PhD student, Jeffrey Sosa-Calvo. Over the next two years, 15 colonies were observed and samples of the ants and fungi were taken for analysis. Using molecular phylogenetic and diversification dating analyses, Schultz and his colleagues were able to determine that this species diverged from the fungus-farming ants over 39 million years ago. They expected this species would feed on lower attine fungi, in accordance with their previous understanding of ant-fungus symbiont fidelity. Surprisingly, this extremely basal genus of the fungus-farming ant cultivates one of the most highly derived fungi, Leucoagaricus gongylophorus (Schultz, et al. 2015). Moreover, this fungus was domesticated by leaf-cutter ants between 2 and 8 million years ago, which raises questions regarding the biological constraints behind ant-fungus fidelity (Schultz, 2007). A. megacephala, like many newly described and potentially undiscovered fungus-farming species, can provide scientists with clues about insect evolutionary life histories. Understanding how these ants speciate, develop mutualisms, and persist through time will be crucial to determine how they persevere in the face of global climate change and widespread deforestation. As a leader in his field, Dr. Schultz and his team will have a lifetime of work discovering new ant species, tracking the evolution of ant-fungus mutualisms, and digging giant holes in the forests of South America. Schultz, T.R. 2007. The fungus-growing ant genus Apterostigma in Dominican amber. In: Advances in Ant Systematics (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): Homage to E.O. Wilson – 50 Years of Contributions (R.R. Snelling, B.L. Fisher, and P.S. Ward, Eds.). Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute 80: 425-436. Schultz, T. 13-MAR-2015. Lecture on Symbiotic Evolution and Species Discovery in Fungus-Farming Ants. University of Maryland, College Park. Schultz, T., Sosa-Calvo, J., Brady, S. G., Lopes, C. T., Mueller, U. G., Bacci Jr., M., & Vasconcelos, H. L. The ant equivalent of a relict colony of Neanderthals cultivating GMO crops. March 11, 2015. American Society of Naturalists. http://www.amnat.org/an/newpapers/MaySchultz.html Andrew Garavito is a first year Master’s student in Dennis vanEngelsdorp’s Lab. He is studying honey bees; with a focus on the nutrition provided by pollen. His research involves looking at the effects that different pollen diets have on the ability of honey bees to combat infections.

Gussie Maccracken is a first year PhD student in the Department of Entomology, University of Maryland, College Park (UMD). Her research explores plant interactions in the fossil record of Cretaceous North America. Specifically, she studies how insect communities change spatially and temporally using insect damaged leaves. Gussie is co-advised by Charlie Mitter (UMD) and Conrad Labandeira (Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History). Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed