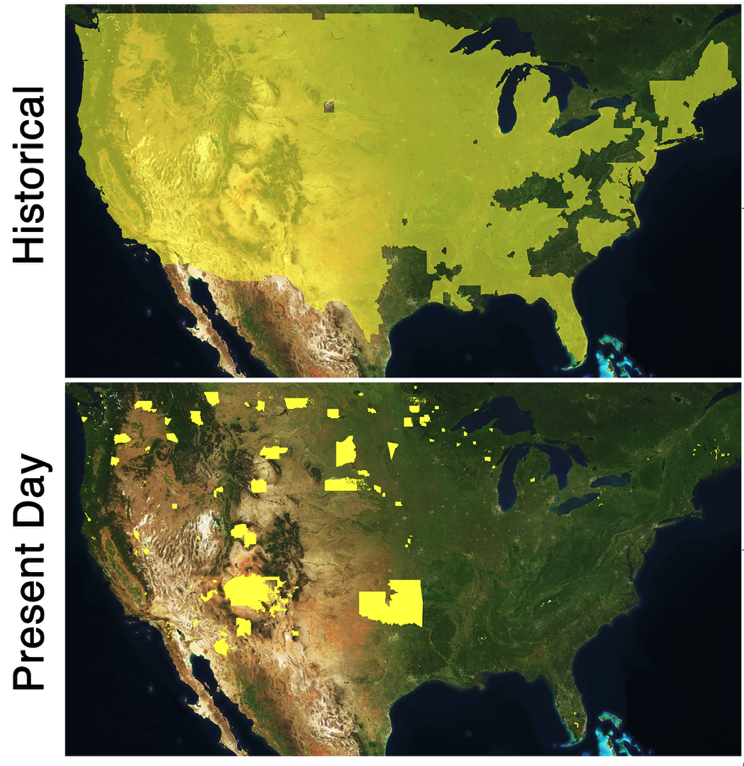

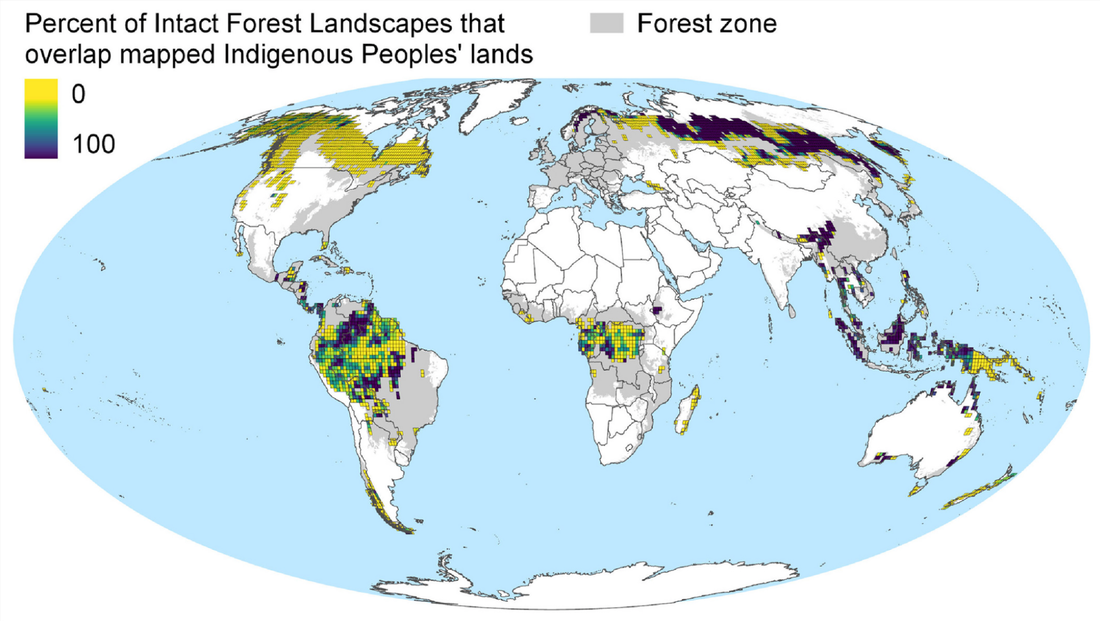

Indigenous Peoples are stewards of approximately four percent of total land in the United Statesl. The lands to which many Indigenous Peoples were forcibly migrated contain fewer resources compared to their historical lands, and much of this land is exposed to more extreme heat, reduced precipitation, heightened wildfire exposure, and reductions in economic mineral value which directly reduces food and water resources. On average, these lands represent a mere 2.6 percent of their historical lands (Figure 1). Forty percent of Indigenous Peoples in the U.S. do not even have land that is recognized by the state and/or federal government2. Indigenous and local communities contribute in many significant ways to biodiversity by creating habitats that are much more diverse and species-rich than typical agricultural landscapes2. Much of the natural habitat within Indigenous-managed land is ecologically equivalent to formally conserved land areas. There is less deforestation and biodiversity is declining more slowly in areas managed by Indigenous Peoples2,4. However, at least sixteen percent of Indigenous-managed land faces high risks from future development and resource extraction. Recent conservation commitments by the countries which make up the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK, US) could also threaten Indigenous land rights. In many countries, once land is formally protected or conserved, activities such as hunting and fishing are prohibited, farming practices are limited and land access restricted, which jeopardizes the Indigenous communities that rely on those land5. Although Indigenous Peoples’ cultures and livelihoods are often deeply embedded in the land, their knowledge of land management and contributory effort is frequently discounted and goes unrecognized6. Only land that falls within formally protected or conserved areas in the US is recognized as conserved land by the government and much of the land managed by Indigenous Peoples falls outside of these conserved areas. A report by the ICCA Consortium estimated that 21% of global land is intact due to the conservation practices of Indigenous Peoples, compared to fourteen percent protected and conserved by countries. Approximately 36% of the intact forest landscape worldwide overlaps with Indigenous-managed lands (Figure 2). While some loss of intact forest landscape on Indigenous-managed lands has occurred since 2000, the loss is less than non-Indigenous-managed lands (8.2% compared to 9.6% across all countries). Further, the deforestation that does take place on Indigenous-managed lands is often without the consent of the Indigenous Peoples who manage that land7. Unauthorized land destruction leads to the loss of life, as well as the loss of land and livelihoods. From 2009 to 2019, more than 300 people – many of whom were members of Indigenous communities – were murdered due to conflicts over land use in the Amazon. These deaths are a result of the increasingly violent clashes between indigenous land right activists seeking to defend their land and commercial investors8. In the US, there have been violent clashes between protestors, indigenous activists and the police over pipelines. Before the Keystone pipeline was vetoed, the 2,735-kilometre pipeline by TransCanada carrying 800,000 barrels of oil a day from Alberta to Texas would have cut through Indigenous territories in Montana, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma.

The vast majority of our planet’s land has been managed for thousands of years to varying degrees by Indigenous peoples, and contemporary losses of biodiversity can be directly attributed to the impacts of colonialism on previously Indigenous-managed lands9. Biodiversity data that was collected from formally protected areas and land managed by Indigenous Peoples in Australia, Brazil, and Canada, indicate for all three countries that Indigenous-managed lands have equal or higher biodiversity than the designated protected areas, which can at least partly be attributed to Indigenous land management practices,7 which are becoming widely referred to as “Traditional Ecological Knowledge” ( TEK). TEK management strategies used by Indigenous Peoples include traditional burning, fishing traps, and forestry practices that are often uniquely suited to an environment. For example, in the regions of the United States now known as Wisconsin, Michigan, and Illinois, the Menominee Tribe practices sustained-yield forest management informed by their spiritual beliefs and contemporary scientific knowledge. These practices ensure that trees are harvested in amounts that will allow for a steady supply of timber far into the future. TEK can also be incorporated into ecological restoration of degraded lands. In the U.S. Pacific Northwest, many Indigenous communities are involved in ecological restoration of shellfish populations and native plant species3. TEK can and should be incorporated into restoration and conservation efforts, and should be incorporated into global efforts to abate the effects of climate change, including plans made a COP26. Historically, conservation has been exclusionary – framed as protecting “pristine” nature from humans, and rejecting the notion that humans and human activity can be part of sustainable, healthy ecosystems. Our conservation framework should protect Indigenous rights to land stewardship, and incorporate Indigenous sustainable land management practices uniquely suited to the area that leverage centuries of regional knowledge. Including and amplifying Indigenous voices in science is of paramount importance to our efforts to mitigate biodiversity loss and the effects of global environmental change, while simultaneously protecting those most vulnerable to its consequences. Authors: Kathleen Ciola Evans is a PhD student in the EspindoLab studying plant-pollinator interactions in agroecological landscapes. Eva Perry is a PhD student in the Burghardt Lab, who is studying the impacts of urbanization on trophic relationships between trees and insects. References and Further Reading: 1. Kimmerer RW (2002). Weaving Traditional Ecological Knowledge into Biological Education: A Call to Action. https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/52/5/432/236145 2. Farrell J et al. (2021). Effects of land dispossession and forced migration on Indigenous Peoples in North America. DOI: 10.1126/science.abe4943 3. Sneed A (2019). What Conservation Efforts Can Learn from Indigenous Communities. Scientific American 4. ICCA Consortium (2021). Territories of Life: 2021 Report. ICCA Consortium: worldwide. Available at: report.territoriesoflife.org. ISBN 978-2-9701386-3-1 5. Schuster R et al. (2019). Vertebrate biodiversity on Indigenous-managed lands in Australia, Brazil, and Canada equals that in protected areas. DOI: 10.1016/j.envsci.2019.07.002 6. Jones B (2021). Indigenous people are the world’s biggest conservationists, but they rarely get credit for it. Vox “Down to Earth” Series 7. Fa JE et al. (2020). Importance of Indigenous Peoples’ lands for the conservation of Intact Forest Landscapes. DOI: 10.1002/fee.2148 8. Villegas A and Robles F (2020). Conflicts over Indigenous Land grow more violent in Central America, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/09/world/americas/central-america-indigenous-conflicts.html 9. Ellis EC et al. (2021). People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for 12,000 years. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2023483118 Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed