|

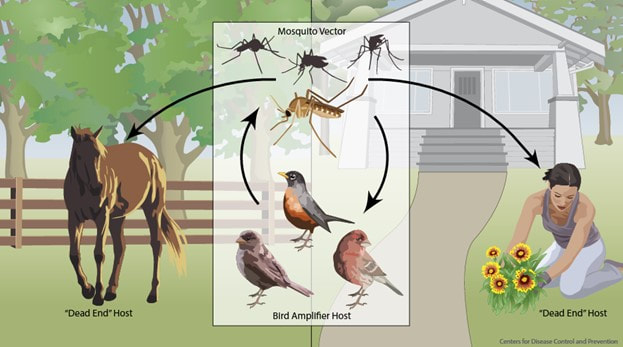

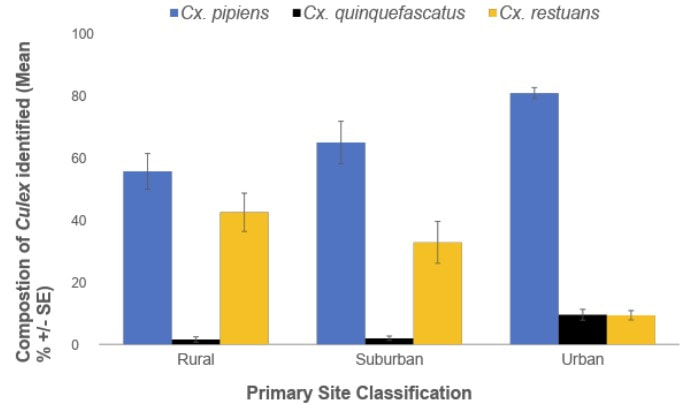

By Ben Gregory These days, most Americans don’t worry too much about malaria, the deadly disease caused by the Plasmodium parasite and spread by Anopheles mosquitoes (Figure 1, left). That wasn’t always the case, however. In fact, during the nineteenth century, malaria was one of the leading causes of death in the United States, affecting nearly every corner of the country, but particularly the south (Hong 2008). Fortunately for those of us living here today, malaria is extremely rare. This is thanks to sweeping control and public health measures taken by the CDC and its predecessor organizations in the early and mid-twentieth centuries. But, more recently, another mosquito-borne disease of concern has spread across the country: West Nile fever. West Nile fever is a potentially deadly illness caused by the West Nile virus, which is spread by mosquitoes in the genus Culex (Figure 1, right). Unlike malaria, which (for the most part) is only transmitted between humans and mosquitoes, West Nile virus is transmitted in a complex cycle between birds, mosquitoes, and humans (Figure 2). To complicate things even further, many different species of Culex mosquitoes can carry the virus from birds to people, and each species appears to play a slightly different role in that transmission cycle based on their habitat, biting preferences, seasonal populations, and many other factors. All of that complexity makes it very hard for public health experts and entomologists to predict where West Nile virus epidemics may occur and take measures to prevent them. That complexity didn’t stop Dr. Arielle Arsenault-Benoit, who set out to determine how cities influence the populations of different Culex mosquitoes that may carry the virus. Cities are unique habitats in many ways. They create lots of different habitat types all clustered close to each other, many of which are great places for mosquitoes to live. Cities also exist along gradients, starting from dense urban centers, moving out through suburbs, and ending in exurban or more “natural” areas. All of these features of cities likely influence which species of Culex mosquitoes can live where (species communities) and thus the risk of West Nile virus. In order to understand how cities might affect the community of Culex mosquitoes, Dr. Arsenault-Benoit chose 15 sites in Washington, D.C., and neighboring Maryland to trap mosquitoes. To make sure she was able to capture the effect of the city habitat, she made sure five of her sites were in the city (Washington, D.C.), another five were in the surrounding Maryland suburbs, and the last five were in rural areas like forests or farms. After three summers of trapping, Dr. Arsenault-Benoit caught over 15,000 mosquitoes, about half of which were Culex. Because many Culex species look very similar and are nearly impossible to distinguish by eye, she used genetic methods to identify nearly three thousand individuals to the species level and then went about the work of investigating whether there was any relationship between species and the type of habitat in which they were found. One of Dr. Arsenault-Benoit's first results indicated that one species, Culex restuans, seemed to arrive much earlier in the summer than any other Culex species. While other species, like Culex pipiens, peaked in population in June and July, Culex restuans was most abundant in April and May. Culex restuans also distinguished themselves from the pack by being far more likely to be found in rural and more natural environments like farms, forest preserves, and areas with more tree cover (Figure 3). Another species, Culex quinquefasciatus, though somewhat uncommon, showed the opposite trend and was far more abundant in densely populated urban areas with fewer trees and more impervious surfaces like pavement, roads, and asphalt (Figure 3). Culex pipiens did not exhibit a strong relationship with any part of the urbanization gradient and was very common everywhere Dr. Arsenault-Benoit looked. However, a subspecies (or “bioform”) of Culex pipiens known as Culex pipiens molestus, which is known to live in underground spaces like sewage systems and subway tunnels, did appear more frequently in cities than outside of them. This is especially significant because previous research suggests that Culex pipiens [ALAB1] molestus may preferentially bite people over other animals. Aside from the interesting ecological insights these results give us, they are also helpful for mosquito control and disease prevention. If we know, for example, that Culex restuans populations rise early in the season and prefer to live in rural and suburban areas, we can target those times and places with control techniques like pesticides to suppress early amplification and transmission of West Nile virus. Further, if it seems like Culex pipiens molestus and Culex quinquefasciatus thrive in highly urban areas with lots of underground space, we can similarly target those habitats for control and even start to think of ways to build subterranean infrastructure that makes it harder for them to breed there.

Research like this, which illuminates the fine-scale geographic trends of mosquito populations, is crucial to public health and makes it clear that mosquito management strategies should be local and consider individual species and their interactions with each other and the environment. Understanding these ecological relationships is even more important as the climate warms, cities grow, and all of these mosquito habitats continue to change. To keep our cities safe, healthy, and habitable, we must continue to learn about the mosquitoes and other animals that live among us. Author bio: Ben Gregory is a PhD student in the Fritz lab at the University of Maryland’s Department of Entomology and is interested in expanding upon Dr. Arsenault-Benoit’s investigations into the effects of urbanization on Culex distributions and ecology. He is particularly interested in using spatial and genomic modelling techniques to map gene flow, hybridization, and local adaptation within the Culex pipiens assemblage along urbanization gradients in the mid-Atlantic United States. Further reading: Arielle Arsenault-Benoit, Megan L. Fritz, in review; Spatiotemporal organization of cryptic North American Culex species along an urbanization gradient. Ecological Solutions and Evidence. Arielle Arsenault-Benoit, Albert Greene, Megan L. Fritz; Paved Paradise: Belowground Parking Structures Sustain Urban Mosquito Populations in Washington, DC. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 1 December 2021; 37 (4): 291–295. doi: https://doi.org/10.2987/21-7023 Sok Chul Hong; The Burden of Early Exposure to Malaria in the United States, 1850-1860: Malnutrition and Immune Disorders. J Econ Hist December 2007; 67(4): 1001-1035. doi:10.1017/S0022050707000472 Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed