|

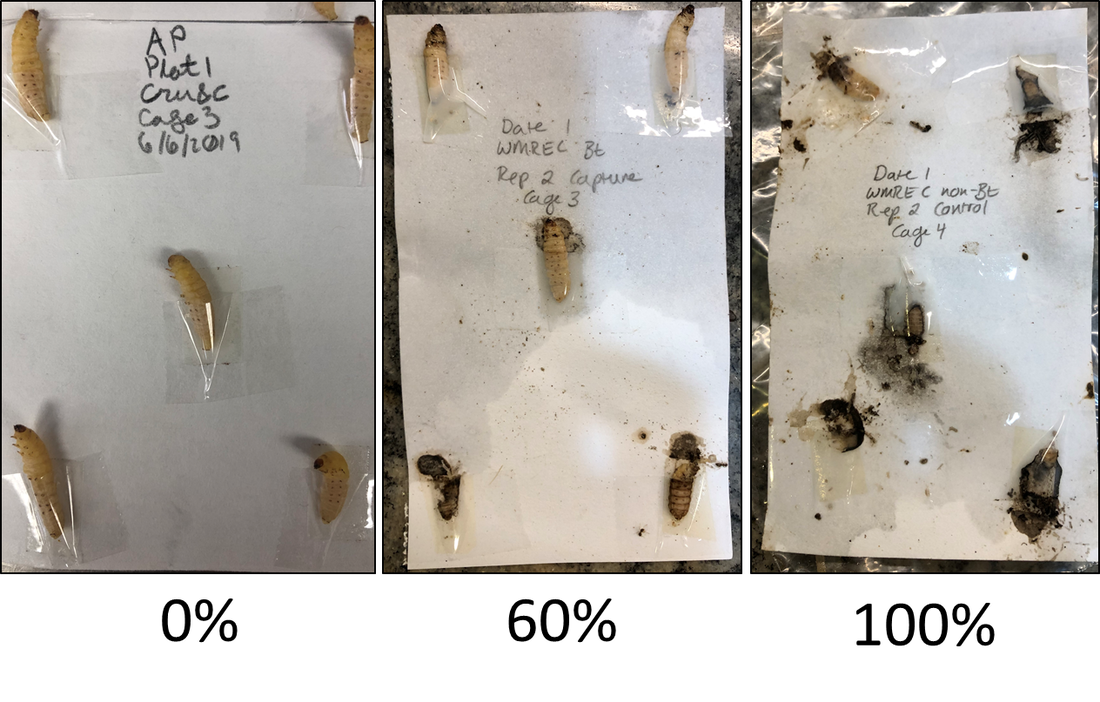

written by: Taís Ribeiro and Brendan Randall It is crucial for graduate students to learn how to design and execute scientific research. Using this research as an informative tool that affects both the livelihoods of people and addresses public needs is essential to communicating science. The ongoing educational partnership between the public and scientists is known as extension and it is one of the pillars of the Department of Entomology. At the first Entomology Research in Progress Seminars, we heard about the work of two researchers that not only perform scientific research but are actively involved in the dissemination and application of their research to solve problems faced by growers and the public. The postdoc Dr. Nathalie Steinhauer and her work in extension in Beekeeping operations, and the PhD Candidate Maria Cramer, who works in agricultural environments. Both of these researchers are passionate about teaching and learning from stakeholders by showing their scientific results and seeing how applied science affects people’s lives.  Figure 1. Beekeeper assessing colony health as a part of the Sentinel Apiary Program. Figure 1. Beekeeper assessing colony health as a part of the Sentinel Apiary Program. Bee Informed Partnership Citizen-participative science and Effectiveness Trials Honey bee health is affected by four main factors: Parasites, Pathogens, Pesticides, and Poor nutrition. However, all of these factors are connected! Understanding how these factors interact is crucial to protect this important commodity and helping the livelihood of the beekeepers. The Bee Informed Partnership (BIP) is a non-profit organization that focuses on research and extension working directly with beekeepers to improve honey bee health and to best support their work. Dr. Nathalie Steinhauer is a post-doc in the BeeLab and also the Science Coordinator of the BIP. In her talk, Dr. Steinhauer explained her work in this organization with citizen science and effectiveness trials. The main citizen participative monitoring programs discussed were the Loss and Management Survey, Sentinel Apiaries, and Tech Transfer Teams. The Loss and Management Surveys are annual voluntary surveys of beekeepers that have been used to monitor colony losses since 2007. The results are used to inform beekeepers of the most successful management practices. The results for 2022 show that even though the number of colonies seems to be stable, the loss rates are higher than acceptable (Aurell et al, 2022). Apart from the survey, beekeepers can participate more actively in the research through the Sentinel Apiary Program (Figure 1). In this program, the participants receive a sampling kit and access to an app to inspect and track the health of their colonies by checking for parasitic Varroa mites and Nosema, a pathogenic microsporidian fungus. Then they receive the results from their colonies and the general results from the research. The Bee Informed Partnership also provides important services such as the Tech Transfer Teams. This service helps commercial beekeepers directly by putting them in contact with trained field agents who visit the colonies, provide on-site hive inspections, and recommend management techniques. Agents also can collect information on pathogens to contribute to other beekeepers. These services encourage regular monitoring of the colonies and bee health, increasing the number of inspections across the country. Another way of helping beekeepers to make informed management decisions is through intervention studies such as effectiveness trials. These trials evaluate how well a product works under “real-world conditions” and can assess whether the product is cost effective. Dr. Steinhauer is currently working on effectiveness trials for a food supplement, testing how effective the product is to prevent brood diseases. Once the results are out, she will be able to discuss with the beekeepers if the product should be used and when to use preventive products to protect their colonies. Understanding early season insecticide impacts in Maryland field corn Agriculture comprises a large portion of human land use and our economy. For example, in Maryland alone, approximately 13% of total land was planted with either corn or soybeans, generating production values of over $750 million in 2021 (USDA NASS, 2021). However, crops do not exist separate from nature, they are a part of it and exist within an ecosystem that contains a wide range of insects, including certain pest insects that may eat crop plants and impact their economic value. In dealing with these pests, farmers may apply insecticides to protect their crops. However, certain corn pest species, such as slugs, present a challenge to farmers and scientists alike because they are not insects, and therefore insecticides are ineffective against them. Also, these applications can have negative ecological impacts due to runoff (Gan et al. 2005) and non-target effects on the predatory insects that eat pests and keep their populations in check (Douglas and Tooker, 2016). Maria Cramer, a PhD Candidate in the Hamby lab studies the relationships and interactions between corn, corn pests, and their natural enemies to advance our knowledge of sustainable pest management of Maryland field corn. In her research-in-progress seminar talk, Cramer presented findings from her three-year field study, which proposes a series of questions: Do early-season insecticides impact pest damage and yield in Maryland field corn? Do early-season insecticides impact the biocontrol of slugs? Cramer set up a field experiment at three research farms across Maryland to determine the efficacy of various insecticide treatments on slugs and other pests in field corn. The experimental plots contained either neonicotinoid seed treatments (NSTs), which are systemic and can be absorbed and translocated throughout the plant, or in-furrow pyrethroids (IFPs), which are sprayed directly into the planting furrow during planting. Control plots were not treated with NSTs or IFPs. She counted healthy and stunted plants, as well as recorded foliar and soil pest damage during the V2-V4 growth stages when corn is most susceptible to early season pest pressure. Additionally, to elucidate the impacts of treatments on slug predators such as carabid ground beetles, she deployed pitfall traps in plots (Figure. 2). She then collected, sorted, and identified the insects and non-insects that fell into the trap. She also deployed sentinel prey cards. These cards contain prey items which attract predators to plots. After 14-16 hours, she returned to the cards and quantified how much predation occurred in each plot (Figure. 3) and then estimate the levels of predation in each treatment. Cramer found that neonicotinoid seed coats did reduce total insect damage in both Bt and non-Bt corn plantings. However, no treatment surpassed action thresholds, which is the point of pest damage at which it would be economically advantageous for a farmer to use a pest control action. In addition, she also found that slug damage was not correlated with reductions in slug damage, demonstrating that sporadic, non-severe pest pressure may render these treatments unnecessary and ineffective in most cases. Corroborating these results are a lack of differences found in slug abundance or predator predation rates between the three treatments.

These results indicate that, for Maryland farmers, preventative insecticides applied at planting are likely not worth the costs. Instead, farmers are likely better off waiting until there is known pest pressure near or beyond action thresholds before bothering to apply insecticides to their fields in most cases. Through this research, growers will be able to make more informed management decisions and reduce seed and input costs by avoiding the purchase and application of unnecessary insecticides. In addition, Maryland farmers can also use this information to help reduce runoff into the Chesapeake Bay watershed, as well as reduce off-target impacts on beneficial insects in agroecosystems through the reduction of unnecessary applications of insecticides, contributing to the growth and adoption of sustainable pest management strategies across Maryland. Authors Taís Ribeiro is a PhD student in the Espíndolab working on the ecology and evolution of oil-collecting bees from South America. Brendan Randall is a second year Master’s student in Karin Burghardt’s lab studying the ecological impacts References Aurell, D., Bruckner, S., Wilson, M., Steinhauer, N., & Williams, G. (2022). United States Honey Bee Colony Losses 2021-2022: Preliminary Results from the Bee Informed Partnership. https://beeinformed.org/2022/07/27/united-states-honey-bee-colony-losses-2021-2022-preliminary-results-from-the-bee-informed-partnership/ Douglas, M. R., & Tooker, J. F. (2016). Meta-analysis reveals that seed-applied neonicotinoids and pyrethroids have similar negative effects on abundance of arthropod natural enemies. PeerJ, 4, e2776. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2776 Gan, J., Lee, S. J., Liu, W. P., Haver, D. L., & Kabashima, J. N. (2005). Distribution and Persistence of Pyrethroids in Runoff Sediments. Journal of Environmental Quality, 34(3), 836–841. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2004.0240 USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (2021). “2021 State Agriculture Overview: Marlyand”. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Quick_Stats/Ag_Overview/stateOverview.php?state=MARYLAND Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed