However, asymptomatic bees are common and can have either low or high virus loads (de Miranda et al. 2012). The story is complicated by the fact that DWV is very closely related to a series of other RNA viruses, such as Varroa destructor virus-1 (VDV-1). And the story gets even more complicated… because of recombination.

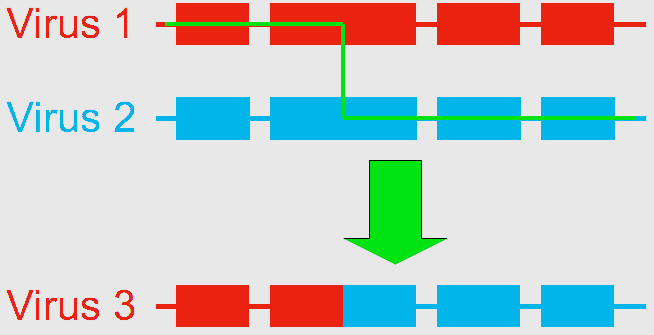

Using next generation gene sequencing, Dr. Ryabov (currently a visiting scientist at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Bee Research Lab in Beltsville, MD) and his colleagues at the University of Warwick, UK, decided to characterize the virus diversity in honey bees. They found that the genome of DWV-like viruses could be divided into three functional parts, or “modules”, any of which were sometimes crossed-over between DWV and VDV. They identified three distinct types of genomes: the 100% DWV genome, and two types of recombinants formed by the association of “modules” from DWV and VDV, which they named VDV-1DVD and VDV-1VVD (Moore et al. 2011). So what was thought to be a single population of viruses is actually a group of variants (VDV-1DVD, VDV-1VVD and DWV). Dr. Ryabov then compared the levels of each variant in honey bee pupae and associated Varroa mites. They found that individual honey bees were usually infected by a mixture of the three variants. Of the three viruses, the recombinant VDV-1DVD’s levels in honey bee pupae was highly associated with its level in associated mites. This suggests this recombinant is more efficiently transmitted between the mite and the honey bee. When Varroa acts as a vector for the DWV, it increases the levels of viruses in contaminated colonies, causes deformities in the affected workers (Fig. 2), and overall results in increased risk of mortality of the whole colony. But what remains to be determined is whether this is caused by 1) Varroa amplifying and introducing more virulent strains of the virus and/or by 2) Varroa suppressing the honey bee immune response. To test those two hypotheses, Dr. Ryabov exposed Varroa-naïve honey bees (collected from a Varroa-free region in Scotland) to DWV either orally (in brood food) or through Varroa mite feeding. They monitored the change in DWV diversity and loads within the host as well as changes in honey bee expressed genes to identify potential antivirus immune responses (Ryabov et al. 2014). They detected changes in expression for a number of genes associated with the immune response of honey bees while in presence of the mites. This suggests that the second hypothesis should be further explored. This study also showed that in Varroa-free colonies (controls), honey bees had highly diverse DWV, though at low levels. When the bees were infected orally, DWV levels remained low, but the composition of the DWV strains changed compared to the controls. When bees were infected through Varroa, two outcomes would happen. Honey bees either showed low levels of diverse DWV strains, or they developed high levels of a single specific variant of DWV or very closely related variants, even though the infecting mite contained a high diversity of strains. By inoculating honey bees through injections (which simulates Varroa feeding), the researchers observed high levels of replication for the recombinant strains containing VDV-1 derived structural gene block. This suggests that these particular strains have an advantage due to the route of transmission. All of this largely supports the first hypothesis that Varroa amplifies more virulent strains of the virus. In conclusion, this example of the shift in virulence of the DWV – from a benign and asymptomatic virus to a serious disease – illustrates the importance of the process of recombination in the generation of various strains of viruses, and how the addition of a vector, and a new route of transmission, can increase the impact of a virus by altering the relative composition of its strains. Bloggers: Meghan McConnell is a Master’s student in Dennis vanEngelsdorp’s Lab. She is currently studying honey bees, with a focus on non-chemical control of Varroa mites. Nathalie Steinhauer is a PhD candidate working in Dennis vanEngelsdorp’s Lab on honey bee health and management practices. Her projects aims to identify and quantify the effects of risk factors associated with increased colony mortality. References: Bowen-Walker, P. L., S. J. Martin, & A. Gunn. 1999. The Transmission of Deformed Wing Virus between Honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) by the Ectoparasitic Mite Varroa jacobsoni Oud. Journal of invertebrate pathology 73(1), 101-106. Highfield, A. C., A., El Nagar, L. C. Mackinde, M. L. N. Laure, M. J. Hall, S. J. Martin, & D. C. Schroeder. 2009. Deformed wing virus implicated in overwintering honeybee colony losses. Applied and environmental microbiology 75(22), 7212-7220. de Miranda, J. R., L. Gauthier, M. Ribiere, and Y. P. Chen. 2012. Honey bee viruses and their effect on bee and colony health. In D. Sammataro & J. Yoder (Eds.) Honey bee colony health: challenges and sustainable solutions. CRC Press. Boca Raton. 71-102. Moore, J; Jironkin, A; Chandler, D; Burroughs, N; Evans, DJ; Ryabov, EV (2011) Recombinants between Deformed wing virus and Varroa destructor virus-1 may prevail in Varroa destructor-infested honeybee colonies. Journal of General Virology, 92(1): 156–161. DOI:10.1099/vir.0.025965-0 Ryabov, EV; Wood, GR; Fannon, JM; Moore, JD; Bull, JC; Chandler, D; Mead, A; Burroughs, N; Evans, DJ (2014) A Virulent Strain of Deformed Wing Virus (DWV) of Honeybees (Apis mellifera) Prevails after Varroa destructor-Mediated, or In Vitro, Transmission. PLoS Pathogens, 10(6): 1–21. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004230 Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed