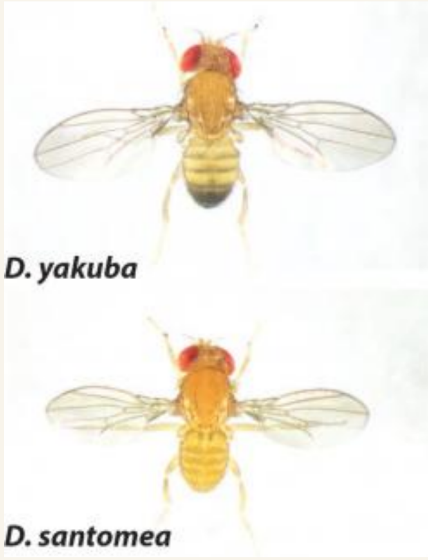

The structure of the male genitalia of the species Drosophila sechellia, with labeled posterior lobe. Image courtesy of Dr. Mark Rebeiz. The structure of the male genitalia of the species Drosophila sechellia, with labeled posterior lobe. Image courtesy of Dr. Mark Rebeiz. One of the greatest mysteries in the field of Evolutionary Biology surrounds the origins of unique morphological structures that have come into existence over evolutionary time. The work of Dr. Mark Rebeiz from the University of Pittsburgh seeks to molecularly characterize the evolutionary changes in developmental mechanisms that control morphology. Using species from the vinegar fly genus Drosophila, Dr. Rebeiz has been able to demonstrate that the emergence of divergent traits, studied through abdominal pigmentation and male genitalia models, are in part the result of changes in the activity of transcription factors and gene regulatory mechanisms during development, rather than the emergence of new genes alone.  Figure 1. The dark abdomen coloration of Drosophila yakuba contrasts with the yellow of Drosophila santomea’s. Image courtesy of Dr. Mark Rebeiz. Figure 1. The dark abdomen coloration of Drosophila yakuba contrasts with the yellow of Drosophila santomea’s. Image courtesy of Dr. Mark Rebeiz. Have you ever been curious how bats evolved wings, how turtles got their shells, or how rhinoceros beetles evolved their horn? Dr. Mark Rebeiz and his lab from the University of Pittsburgh study the field of evolutionary development, which aims to address the evolution of these and other unique organismal features. The creation of a morphological structure is influenced by vast gene regulatory networks, orchestrating when and where genes that confer unique cellular behaviors are activated. One component of these networks, of particular significance, is enhancers – short regions of DNA that can become bound by proteins and increase transcription of particular genes. Dr. Rebeiz’s work focuses on how differences in the expression of these networks underlies the evolution of morphological “novelties” that evolved in the recent past. By using closely related species, his lab can look at novel traits present in some species but not their closest relatives, and determine the traits’ genetic origins. In particular, his work uses species from the vinegar fly genus Drosophila to study the traits of abdominal pigmentation and male genitalia as models of trait divergence and novel structures, respectively. Pigmentation patterns represent a trait in Drosophila that is both rapidly evolving and easy to observe, making it ideal for genetic study. Dr. Rebeiz’s first research project entailed identifying the specific gene regulatory mechanism responsible for the different abdominal coloration of two closely related species, D. yakuba and D. santomea (Figure 1). Although both species have the same genes for pigment production, the level and location of gene expression is different, which could be indicative that the network’s enhancers are being expressed in new locations and ways. Through a selective breeding technique called introgression mapping, Dr. Rebeiz’s team identified one of the main genes responsible for abdominal pigment patterns (AbdB) and its enhancers, and demonstrated that D. santomea’s lack of dark pigment is related to at least one enhancer expressing differently than D. yakuba(1,2). These findings demonstrate that quantifiable differences in enhancers influenced the divergence of different pigment patterns, rather than new genes entirely.  Figure 2. The structure of the male genitalia of the species Drosophila sechellia, with labeled posterior lobe. Image courtesy of Dr. Mark Rebeiz. Figure 2. The structure of the male genitalia of the species Drosophila sechellia, with labeled posterior lobe. Image courtesy of Dr. Mark Rebeiz. Dr. Rebeiz’s lab also uses Drosophila flies to study how new physical structural features can evolve in organisms. To investigate this, he and his lab looked at a feature present in more recently diverged species (such as D. melanogaster), but not in older species - a lobe on the male genitalia called the posterior lobe (Figure 2). Based on previous work they had done on Drosophila optical nerve genes, Dr. Rebeiz and his collaborators predicted that rather than new genes being present to explain the new structure, genetic regulatory elements of old genes were being co-opted from other tissues to have new functions (3). They discovered that the gene required for development of the posterior lobe, called Pox-neuro, was indeed also present in older Drosophila species - suggesting that the gene had a different purpose in their ancestors before its new function arose(4). His team then set out to identify the particular genetic enhancer responsible for the expression of Pox-neuro in the posterior lobe. Using transgenes of this enhancer that expressed green fluorescence, they were able visualize where this enhancer was activating transcription of Pox-neuro during the formation of posterior spiracles in Drosophila larvae, ultimately suggesting that gene networks can be bi-functional in unexpected ways. Through live imaging of the posterior lobe’s development, Dr Rebeiz’s lab also determined a potential target gene (short-stop) is regulated by genes such as Pox-neuro. This target gene regulates tubulin, or the “cytoskeletal” structure of cells, which results in influencing the relative size of the lobe and ultimately may provide a physical mechanism by which the lobe evolved its shape (Rebeiz and Smith, unpublished). Dr. Rebeiz’s findings shed light on the different genetic mechanisms that can underlie a recently evolved trait in an organism. By using Drosophila flies as a model, these mechanisms can be applied to future research of other species, allowing researchers to discover the molecular pathway to evolutionary divergence in many different organisms, and raising questions about the behavioral evolutionary factors that may lead to the structure’s development. More information about Dr. Rebeiz and his lab’s research can be found at his webpage. Liz Brandt is a M.S. student in Dr. David Hawthorne’s lab studying the detoxification gene pathways of the honey bee. Anna Noreuil is a Ph.D. student in Dr. Megan Fritz’s lab investigating the neurogenetic mechanisms underlying human host preference in Culex mosquitoes. References: 1. Jeong, S., M. Rebeiz, P. Andolfatto, T. Werner, J. True, and S.B. Carroll (2008) The evolution of gene regulation underlies a morphological difference between two Drosophila sister species. Cell 132:783-793 2. Rebeiz, M., M. Ramos-Womack, S. Jeong, P. Andolfatto, T. Werner, J. True, D.L. Stern, and S.B. Carroll (2009) Evolution of the tan locus contributed to pigment loss in Drosophila santomea: a response to Matute et al.. Cell 139:1189-1196 3. Rebeiz M*, Jikomes N*, Kassner VA, Carroll SB (2011) The evolutionary origin of a novel gene expression pattern through co-option of latent activities of existing regulatory sequences. PNAS 108:10036-43 4. Glassford WJ, Johnson WC, Dall NR, Liu Y, Boll W, Noll M, Rebeiz M (2015). Co-option of an ancestral Hox-regulated network underlies a recently evolved morphological novelty. Developmental Cell, 34(5): 520-531 Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed