What we don’t know could hurt us: the mystery of pesticide use and consequences for insects11/27/2019

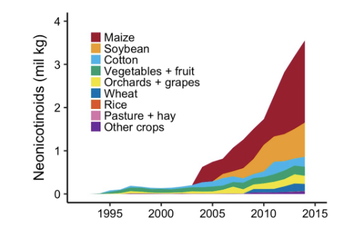

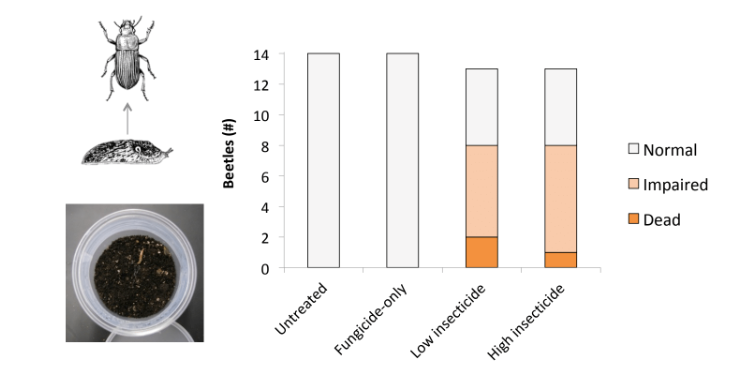

written by: Maria Cramer, PhD student, Hamby Lab and Veronica Yurchak, PhD student, Hooks Lab Dr. Maggie Douglas, an assistant professor from Dickinson College, managed to stump most of a room full of entomologists when she asked them if pesticide use in United States agriculture was going up or down over time. There were a few embarrassed laughs, but Douglas reassured everyone; “It’s a complicated question. There’s disagreement in the scientific community.”  Figure 1. Neonicotinoid use over time in the United States. The greatest rise is in corn and soybeans: almost all seeds are treated. Figure 1. Neonicotinoid use over time in the United States. The greatest rise is in corn and soybeans: almost all seeds are treated. A running theme for Douglas, who completed her PhD at Penn State University, is that quantifying pesticide use in the U.S. is more complicated than it seems. Douglas’ work centers around understanding pesticides for an important reason--she wants to know how they relate to reports of insect declines that are making headlines. She investigates how insecticides (pesticides targeting insects) affect pollinators and other insects. But, back to the question of whether insecticide use is increasing or decreasing. According to Douglas, it’s hard to tell because insecticide use can be measured in different ways: you can look at the percentage of land treated, the weight of insecticide products applied, or the potency of the insecticides. Douglas collected data from government sources and standardized the data using potency in terms of the dose needed to kill a honey bee. While the overall weight of insecticides has declined over the past 20 years, making it seem that pesticide use is decreasing, the number of lethal doses has risen dramatically. This change has largely come from regions of the United States that grow corn and soybeans, and by integrating data from additional sources, Douglas showed that the increase is being driven by neonicotinoid seed treatments (Figure 1). Neonicotinoids, known as neonics, are a type of insecticide that is relatively safe for mammals but acutely toxic to insects. They are applied to crops as seed treatments, where the seedling takes up the insecticidal compounds through its roots and circulates them as it grows. Douglas showed that nearly all corn grown in the U.S. is treated with neonic seed treatments, and that the amount per seed is increasing. In her PhD working in the Tooker Lab, Douglas explored how neonic seed treatments might affect natural enemies. She studied soybean production, where slugs are a major pest problem in the spring. She wanted to know if seed treatments harmed the predatory beetles that normally feed on slugs. She found that the neonic seed treatments were harmlessly absorbed by slugs when they ate soybean plants, but poisoned slug eating beetles (Figure 2). She even found that fields that used seed treatments had lower yields, possibly because the treatments killed slug eating predatory beetles. Douglas found that neonics did exactly the opposite of what a farmer might want them to do: they decreased soybean yield by killing non-target beneficial insects. One of the reasons why non-target impacts from neonics are so concerning is that there isn’t regular pest pressure in most cases to justify the collateral damage they might cause. Nevertheless, the majority of the seed sold in the United States comes pre-treated and many farmers don’t even know exactly what is on the seed! This is due to a lack of required labeling for seed treatments and makes collecting data on neonic use a real challenge. A major difficulty in understanding neonic seed treatment use and environmental impact is this lack of transparency.

In her current lab, Douglas continues to work on this important topic. She integrates data from the USDA, USGS, and EPA to create detailed maps showing the number of toxic doses (the same measurements she used to understand if pesticide use was increasing or decreasing) over time and location. She’s collaborating with other researchers to use these maps to understand insecticide impacts on beneficials such as pollinators. Douglas’ research serves an important role: she looks at broad trends in pesticide-use, gathering data from diverse sources, and asking tricky questions. She left everyone in the room with a less tangled story of pesticide use patterns in the U.S., but at the same time suggested yet another question to explore: As we research the impacts of pesticides on insects, how do we integrate farmer decision-making and account for the lack of transparency surrounding chemicals used in seed treatments? Works Cited: Douglas MR, Sponsler DB, Lonsdorf E V., Grozinger CM, 2019. Rising insecticide potency outweighs falling application rate to make US farmland increasingly hazardous to insects. bioRxiv 715763. Douglas MR, Tooker JF, 2016. Meta-analysis reveals that seed-applied neonicotinoids and pyrethroids have similar negative effects on abundance of arthropod natural enemies. PeerJ 1–26. Douglas MR, Rohr JR, Tooker JF, 2015. Neonicotinoid insecticide travels through a soil food chain, disrupting biological control of non-target pests and decreasing soya bean yield. J. Appl. Ecol. 52, 250–260. Douglas MR, Tooker JF, 2015. Large-scale deployment of seed treatments has driven rapid increase in use of neonicotinoid insecticides and preemptive pest management in U.S. Field crops. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 5088–5097. Biographies: Maria Cramer is a PhD student in the Hamby Lab studying non-target effects of pyrethroid insecticides and RNAi in field corn. Veronica Yurchak is a PhD student in the Hooks Lab studying the potential benefits of interplanted living mulches for weed suppression, insect natural enemy enhancement and pollinator conservation in vegetable systems. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed