Fig. 1. Dr. Jessica Ware. Source: American Museum of Natural History Fig. 1. Dr. Jessica Ware. Source: American Museum of Natural History Written by: Maria Cramer, Ebony Argaez and Graham Stewart As research entomologists, it’s easy to focus on one tiny area of study. In fact, this is a normal way to do research. So when Dr. Jessica Ware, the speaker for the University of Maryland’s entomology colloquium, talks about her research interests which cover many areas including dragonfly evolution and global migration, termites, and cockroaches, she is often asked why she chooses to study so many different things. Her answer is simple; it’s ok to study more than one group at once. It’s ok to let curiosity about the incredible diversity of insects drive your interests. Dr. Ware also challenges the idea that research is disconnected from broader societal issues. As a Black woman in entomology and the first Black woman in every research group and program she has been in, Dr. Ware knows first-hand that many social forces determine who gets to study entomology. With her passion for diverse insect groups, and her commitment to equity and inclusion, Dr. Ware structured her talk around three questions: What drives insect diversity? Where do dragonflies go? And who gets to be an entomologist?

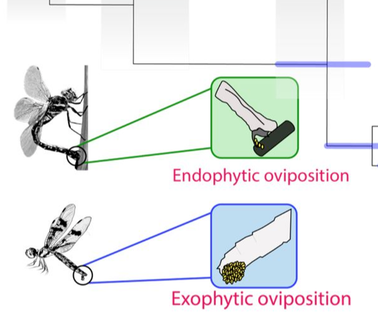

Dr. Ware focused on one characteristic of dragonflies to explain how we can learn more about how dragonfly groups are related to each other and what traits are ancestral. This characteristic is whether a dragonfly has an ovipositor, a specific egg-laying structure. Dragonflies with what’s termed endophytic oviposition have a knife-like ovipositor that they use to cut into plants and lay eggs. Dragonflies with exophytic oviposition don’t have an ovipositor and fling their eggs into water unguarded (Figure 2). Although the eggs are not protected by plant tissue in the second case, the female dragonflies can lay eggs more quickly, making them less vulnerable to predators. Dr. Ware was curious about how the ancestors of modern dragonflies laid their eggs-- did they have ovipositors or not? To answer this question, she compared the genomes of dragonflies across different families that were more and less closely related. She found that unrelated dragonfly families had exophytic oviposition, indicating that ancestral dragonflies all had ovipositors, and some families lost them in separate evolutionary events [1]. By using genetic techniques, it became clear how the presence or absence of the ovipositor played a role in the relationships between dragonfly families, showing how multiple groups can evolve the same characteristic separately if it is beneficial. Where do dragonflies go?  Fig. 3. Pantala favescens (wandering glider) dragonfly. Photo by Jeevan Jose. Fig. 3. Pantala favescens (wandering glider) dragonfly. Photo by Jeevan Jose. A second fascinating focus of Dr. Ware’s research centers on the migration of the dragonfly Pantala flavescens, commonly called the wandering glider (Figure 3), which can cover thousands of miles and cross entire oceans. The incredible journey of this dragonfly is possible because of an enlarged area on its hindwing that allows it to catch trade winds and glide over vast distances with relatively little effort. P. flavescens' dispersal ability has led to its global distribution, with populations scattered across every continent except Antarctica. The P. flavescens migration isn't just a spectacle, however--it also presents a unique case study on gene flow (how related populations of P. flavescens are to each other, or how much genetic information is being exchanged between them) at a global scale. Dr. Ware and her colleagues set out to determine the rate of gene flow by analyzing DNA among P. flavescens populations from Japan, India, Guyana, and the United States [2]. They found a high degree of gene flow among these disparate populations and suggested that geographic separation does not necessarily mean genetic isolation in this species. Many of the different populations of P. flavescens may make up one big global population. Who gets to be an entomologist? Dr. Ware also highlighted her extensive efforts promoting diversity and inclusion in the field of entomology [3]. She is part of a group called #BlackinEnto whose goal is to foster community, inspire others and share a common passion in insects. During Black History Month, in February, they host a #BlackInEnto week with panels and workshops on topics ranging from cooking with insects to colonialism in entomology. Some of the content from this week can be found in a YouTube playlist called BlackInEnto. She is also the founder of a group called Entomologists of Color (EntoPOC) to increase participation of people of color (POC) in entomological societies with the goal of lowering achievement gaps (Figure 4). They provide free memberships to students of color who may not have financial access to ESA and other entomological societies. These students are then featured on their page. To further support students of color, EntoPOC does outreach like publishing research articles about the disparity of BIPOC students in entomology, doing interviews, and collecting donations. Dr. Ware is also part of Black in Natural History Museums. During the week of October 17-23, they hosted a Black in Natural History Museums Week which celebrated Black people working in natural history museums and encourages engagement among Black professionals. Each day has events and its own theme, like #BINHMBehindTheScenes and #BlackInBiodiversity.

These are all ways Dr. Ware participates to diversify the field of entomology, counteract the disparities BIPOC face, and achieve a dream she described having that any kid of color can be an entomologist if they want to be. Dr. Ware’s interest in diverse insect groups led her to looking at different dragonfly egg laying strategies, as well as their migration pattern, while the lack of diversity in the field of entomology drives her to participate in programs that foster a more diverse field. References and further reading: [1] M. Kohli et al., “How old are dragonflies and damselflies? Odonata (Insecta) transcriptomics resolve familial relationships,” bioRxiv, pp. 1–15, 2020, doi: 10.1101/2020.07.07.191718. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.07.191718v1.abstract [2] D. Troast, F. Suhling, H. Jinguji, G. Sahlén, and J. Ware, “A global population genetic study of pantala flavescens,” PLoS One, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 1–13, 2016, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148949. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148949 [3] Evangelista DA, Goodman A, Kohli MK, Bondocgawa Maflamills SST, Samuel-Foo M, Sanchez Herrera M, Ware JL, Wilson M F (2020) Why Diversity Matters Among Those Who Study Diversity, American Entomologist, Volume 66, Issue 3, Pages 42–49, https://doi.org/10.1093/ae/tmaa037 Authors: Maria Cramer is a PhD student in the Hamby Lab studying how insecticides used in corn can impact beneficial insects like predatory beetles. Ebony Argaez is a M.Sc student in the Pick Lab studying the effectiveness of RNAi in diverse insects. Twitter: @em_argaez Graham Stewart is a PhD student in the Palmer Lab studying carbon cycling in restored and natural freshwater wetlands. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed