written by Leo Kerner We know that pollinators play a vital role in the health of every agroecosystem, but how can the agroecosystem benefit pollinators? Kathleen Evans, a PhD student in the Department of Entomology at the University of Maryland, is attempting to figure this out. Working in the EspíndolaLab, Katy is focused on plant-pollinator interactions and loves to engage with the public informing them of the importance of insects. She came to speak at our colloquium about her most recent project on floral diversification and its effects on beneficial arthropods and ecosystem services among edamame. Previously, Katy has worked on pollinator health in agroecosystems and sustainable honeybee management practices, and now her work takes a closer look at understanding plant-insect interaction in agroecosystems. [Seminar Blog] Serving the Public as a Government Scientist: Career tracks and opportunities11/18/2022

written by: Amanda Brucchieri and Robert Salerno

Have you ever thought of pursuing a career within the federal government? Do you know what opportunities exist for research, extension, and policy/regulation? During this week’s colloquium talk, Dr. Chris Peterson, an International Food Security, and Pest Management Professional working for the USDA Foreign Agriculture Service, passed on his knowledge and wisdom about career paths within the federal government. He wanted to bring a personal perspective to the field of government employment and help students navigate their next steps as future scientists so he came on his own time and was not speaking as a representative of the USDA. Dr. Peterson holds a Ph.D. in Entomology and Toxicology from Iowa State University and has held several positions within the Forest Service, Peace Corps, and currently, the Foreign Agricultural Service. written by: Ben Burgunder & Eric Hartel

How can modeling and mathematics inform our research of macroevolution? Towson University professor Dr. Daniel Caetano visited the University of Maryland's entomology department to deliver a lecture on his many research interests. Dr. Caetano explores evolution through mathematical modeling and novel approaches to phylogenetic comparative methods. Phylogeny is the scientific approach to understanding the evolutionary relationships between groups of organisms and phylogenomics is the application of genomics to phylogenetics research. Dr. Caetano explained that his research is supported by two pillars: trait evolution and species diversification. He discussed two examples of developing novel methodology from published, publicly available datasets. written by: Minh Le

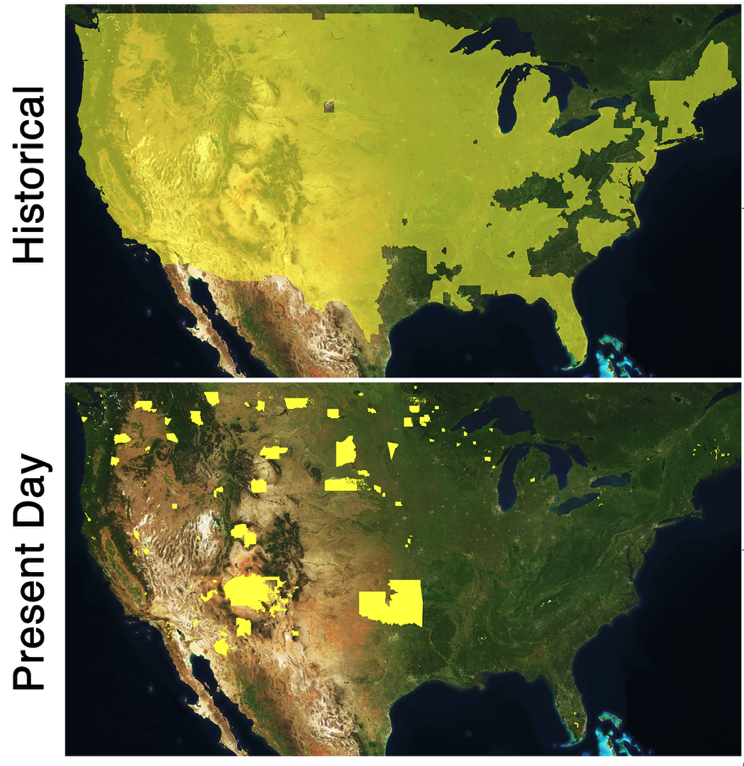

Not many people have heard of the sorghum plant, so you might be surprised to know that it is grown in 21 states (Figure 1)! The “Sorghum Belt”, or area comprising states that have abundant sorghum production, stretches from South Dakota all the way down to southern Texas (National Sorghum Producers). The sorghum plant produces nutritious grain, which is an important ingredient for livestock feeds as well as a whole grain alternative to people with low gluten tolerance or who suffer from celiac disease. Besides its nutritional benefits, sorghum production can have a positive impact on the environment and sustainability efforts, as the sorghum bushels can be extracted for ethanol, a renewable source of fuel, and require one-third less water to grow compared to other feedstocks (National Sorghum Producers). Despite its agricultural and environmental importance, as with other widely cultivated agricultural crops, these plants are a buffet for pest insects whose voracious appetite cause significant economic damage every year. A prominent invasive pest feeding on sorghum in the US is the sorghum aphid (Melanaphis sorghi). These insects use their syringe-like mouthparts to pierce and suck juices from plant tissues, damaging them. In 2013 and 2014, it is estimated that these aphids caused 50 to 100% of crop loss, and in 2015, sorghum producers in the Rio Grande Valley lost approximately 31 million dollars. The entomology colloquium welcomes Dr. Jocelyn Holt, a researcher at Rice University, Texas, who provided insight into her research on the population genetics of sorghum aphids across the US and the symbiotic microbiota that is associated with them. written by: Darsy Smith and Benjamin P. Gregory

How do insects that live in dry environments like deserts keep from drying out, and how might these adaptations help them adjust to our constantly changing world? For our first colloquium of October, the Entomology Department welcomed Dr. Henry Chung, an assistant professor at Michigan State. Dr. Chung’s research investigates the genetic mechanisms underlying insect adaptations to different environmental conditions, particularly dry ones. Just like humans, insects need water to live their lives, so making sure they don’t dry out–or desiccate–is vital to their survival. So how do insects that live in hot and dry conditions prevent desiccation? One of the most important pieces of an insect’s defense against desiccation is its epicuticle, the waxy top layer of its exoskeleton, and the chemical pieces that make up this epicuticle, called cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs). writen by: Demian A. Nuñez and Darsy Smith

The end of the semester is here! For the last weekly seminar series, the Entomology Department welcomed Dr. Jason Rasgon to speak about his research and experience with new molecular tools for gene editing in arthropods. Dr. Rasgon completed his Ph.D. at the Entomology Department of the University of California, Davis. There he had the opportunity to conduct research on Wolbachia infection dynamics, a naturally occurring bacteria that lives within several insect taxa and is passed from one generation to the next through their eggs. Since early in his career, he has successfully answered research questions in various systems, which has given him the experience to lead projects across a wide range of biology-subdisciplines. Currently, he is a professor of Entomology and Disease Epidemiology at Pennsylvania State University, where he integrates population biology, ecology, molecular tools, and theory to answer both fundamental and applied questions in genetics. The main goal of Dr. Rasgon’s lab is the development of new methods that can be used to introduce transgenes into natural disease vector populations.  written by: Mintong Nan and Lindsay Barranco Let’s face it. Graduate school can be a wonderful experience, but there are stressors aplenty - from financial worry to time management, coping with expectations of yourself and others, all in a field of scientific research - where the nature of the work involves a high degree of uncertainty and uncharted territory1, 2. These cumulative pressures can all lead to a great deal of stress for the graduate student, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thankfully, skilled and caring professionals like Ms. Simone Warrick-Bell are there if needed. Ms. Warrick-Bell has been a graduate student academic counselor for the University of Maryland (UMD) Graduate School since early 2020, and prior to 2020 she was a care manager with the UMD counseling center. She holds a Master’s in Counseling Psychology and is a licensed Clinical Professional Counselor. Her works include individual consultation sessions and leading graduate student circle sessions, which were created solely to support UMD graduate students. The entomology department was happy to welcome Ms. Warrick-Bell to our Friday seminar series and to hear more about the services she provides through the Graduate School. written by: Ebony Argaez and Minh Le

The natural world is teeming with gorgeous and awe-inspiring biological structures, patterns, and colors that cannot be described via mere words alone. During the digital age, accurate and realistic imagery of these specimens can be obtained through the lens of a camera. However, the camera can only capture what is, not what could have been. Exquisite imagery requires the gentle and imaginative hand of an artist like Taina R. Litwak a scientific illustrator with the US Department of Agriculture’s Systematic Entomology Lab and the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of Natural History who joins this week’s entomology colloquium at the University of Maryland to talk about entomological art in the digital age. written by: Eric Hartel

Combining different schools of thought or discipline can lead to more meaningful discovery and understanding. The work of Dr. Chris Hamilton addresses this by studying Aphonopelma, a group of tarantulas that are found in the incredible and unique biome of sky islands in the southwestern United States and Mexico. This group of tarantulas are important as a marker for understanding the region, and hold a place of cultural significance in the San Carlos Apache creation story. What is a sky island you ask? They are made of mountain ranges that are surrounded by desert valleys. These mountains create interesting temperature and humidity gradients that play host to various stratified environments. These environments are similar to ocean islands because the deserts take the role of the impassable ocean, isolating organisms to specific islands if they can not cross the desert. The tarantulas in this area have no way to cross the large deserts and are partitioned into their niches across this area. The speciation and diversity of these tarantulas can shed light on the geologic history, evolution, and current state of this understudied diversity hot spot. [Seminar blog] The end of spray and pray? Alternative ways to control spotted wing drosophila4/25/2022

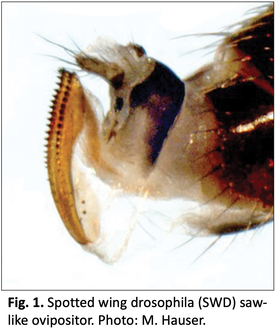

written by: Maria Cramer and Huiyu Sheng Spotted wing drosophila (SWD) is a pest that causes backyard berry growers and commercial farmers alike a lot of grief. Native to Eastern Asia, this fruit fly (closely related to the famous Drosophila melanogaster) first appeared in the mainland U.S. in 2008. Like other fruit flies, SWD lays eggs in fruit, but unlike others, it has a sharp ovipositor that allows it to cut through fruit skin and lay eggs inside (Figure 1). Because of this, SWD larvae aren’t restricted to rotting or damaged fruit– they can infest otherwise perfect produce. Their favorite fruits include raspberries, blackberries, grapes, and cherries. Besides the ick-factor, the wounds from cutting into fruit can introduce microorganisms that cause the fruit to rot. To make things worse, because they’re inside fruit, the larvae are protected from insecticide sprays (Figure 2). This means farmers have to instead target the adult flies, which requires frequent insecticide applications. Spraying insecticides over and over has many downsides; it’s expensive for farmers, it could hurt other insects, and it could even put pressure on SWD to develop resistance to the chemicals themselves, making them less effective. Dr. Torsten Schöneberg would love to see an end to this “spray and pray” approach for managing SWD. Currently a researcher at Agroscope in Switzerland, Dr. Schöneberg recently completed a postdoc in the Hamby Lab at the University of Maryland. He returned to the Entomology Department’s weekly seminar series to give an update on the research he did during this time. [Seminar Blog] Mitey talk: Dr. Zachary Lamas' exit seminar on honey bee's disease transmission4/19/2022

[Seminar Blog] All for one and one for all, Dietary specialization in neotropical army ants3/28/2022

written by: Max Ferlauto and Madeline Potter

Most tiny insects go unnoticed, yet tiny insects can greatly impact humans and our ecosystems. Dr. Nicole Quinn has spent the past five years researching how to utilize particularly tiny insects, known as parasitic wasps, to help manage invasive insect pests (non-native species that cause harm). The invasive pests Dr. Quinn focused on were the brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys) during her PhD research at Virginia Tech University, and the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) during her postdoctoral research with USDA-ARS Beneficial Insects Introduction Research Unit and University of Massachusetts. Her research helps reveal and enhance methods to effectively control invasive insects. written by: Angela Saenz and Taís Ribeiro

Our identity and background shape how we work. This is not different in science. In their seminar for the University of Maryland Entomology department, Dr. Lauren Esposito gave a presentation entitled "Why Entomology Needs Queer Voices", sharing their story and how it has inspired them to work towards increasing diversity and inclusion in STEM. written by: Taís Ribeiro and Darsy Smith

Have you ever thought about how scientists know how organisms are related? Similar to how humans can use family trees to know who are their relatives, scientists can study the relationship between groups of organisms by constructing phylogenetic trees. These phylogenetic trees are two-dimensional diagrams that can represent the evolution and diversification of a group of organisms (Figure 1). Phylogenetic trees can show what organisms are in the base (or the root) of a tree, and more closely related groups in closer branches. Phylogenetic relationships help us understand the diversity of species and address ecological and evolutionary questions. Traditionally phylogenies were constructed using morphological data – what organisms look like—but advances in molecular phylogenetics, first with a few genetic markers and now with phylogenomic studies that use hundreds of genes, have transformed our understanding of these biological questions. [Seminar Blog] USDA Protects US Agriculture Using Sterilized and Genetically Engineered (GE) Insects2/3/2022

Written by: Krisztina Christmon and Veronica Yurchak

From its first use in the 1950’s through present day, scientists have been trying to manage insect pests using the sterile insect technique (SIT). Today, USDA ‘s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) - Plant Protection and Quarantine unit uses SIT as part of their Fruit Fly Exclusion and Detection Program, the goal of which is to protect US Agriculture from potentially invasive and damaging exotic fruit fly species. Dr. Corey Bazelet is responsible for coordinating this fruit fly program and presented her work as part of the University of Maryland’s Safeguarding American Agriculture seminar series. [Seminar Blog] Slovenia and Its Honeybee Practices: Small Country, Big Beekeeping Successes2/2/2022

Written by: Patrick McNamara and Jonna Sanders

Dr. Peter Kozmus is a zoologist, author, diplomat, and worldwide advocate for political action to protect honeybees, insects, and insect diversity. He is a leading figure at the world honeybee association, Apimondia, as well as among Europe’s Entomologists focused upon honeybee genetics. Since 2011, Dr. Kozmus has been the Director of the Republic of Slovenia’s Carniolan Bee Breeding program at the Slovenian Beekeeping Association, Čebelarska zveza Slovenije. This program strives to protect Apis mellifera carnica, the Carniolan bee, which is the indigenous honeybee subspecies in Slovenia. A graduate of the Biotechnical Fakulteta at Slovenia’s University of Ljubljana, his Doctoral research explored the morphological and molecular markers of bumblebees. In 2014, he joined the Slovenian Beekeeping Association, which is a honeybee industry advocacy center, a research institute, and a powerful political ecological voice in Slovenia. In 2017, Dr. Kozmus was elected to the position of Vice President of Apimondia. [Seminar Blog] I declare a plant-insect war: The arms-race and profiteering of species interactions.12/16/2021

We may think of herbivores, or animals that feed on plants, as large lumbering creatures grazing on grass, but most of them are, in fact, insects (Forister et al., 2015). Herbivorous insects interact with the predators that seek to eat them and the plants they rely on for food. But from a plant’s perspective, the insect herbivores are the predators. Plants rely on various tools to reduce the onslaught of attack from these foliage feeders. For example, they can utilize sticky appendages called trichomes, and deploy stinky or toxic chemicals. These interactions that originate from the plant and have impacts on herbivores are known as ‘bottom-up effects’ (Figure 1). Due to the abundance of insect herbivores in nature, they are also important food sources for insect predators and parasitoids. These interactions, which involve herbivore predators, are an example of ‘top-down effects’ (Figure 1).

written by: Lasair ni Chochlain Case studies are one teaching tool that can be utilized to engage students, improve learning outcomes and inclusion in the classroom. Dr. Ally Hunter presented her work exploring the effectiveness of case study pedagogy at a Department of Entomology seminar earlier this semester. Dr. Hunter began this work in her doctoral dissertation, completed at University of Massachusetts – Amherst. Now a postdoctoral fellow at UMass Amherst, she utilizes case studies in her undergraduate science classrooms to promote inclusive pedagogy. The advantage in using case studies in scientific teaching is that the stories, with rich narratives, convey scientific content and concepts while also contributing to the maintenance of situational interest which facilitates undergraduate learning. Here, we dive deeper into the methodology of Dr. Hunter’s educational research, to illustrate how her findings can be applied in entomology classrooms and beyond.  Fig. 1. Dr. Jessica Ware. Source: American Museum of Natural History Fig. 1. Dr. Jessica Ware. Source: American Museum of Natural History Written by: Maria Cramer, Ebony Argaez and Graham Stewart As research entomologists, it’s easy to focus on one tiny area of study. In fact, this is a normal way to do research. So when Dr. Jessica Ware, the speaker for the University of Maryland’s entomology colloquium, talks about her research interests which cover many areas including dragonfly evolution and global migration, termites, and cockroaches, she is often asked why she chooses to study so many different things. Her answer is simple; it’s ok to study more than one group at once. It’s ok to let curiosity about the incredible diversity of insects drive your interests. [Seminar Blog] Reaching maturity? Malaria parasites’ developmental journey through the mosquito11/4/2021

Written by PhD students Arielle Arsenault-Benoit & Minh Le

Malaria is a mosquito-borne illness that has plagued human civilization for millennia (Cox 2010), and continues to infect many people, with over 200 million documented cases in 2019 (World Health Organization, 2020). Preventative interventions and treatments are available for those that can access them, yet according to the WHO, there are 400,000 annual deaths worldwide, and nearly 70% of those are children under 5 years old. Among those interventions are insecticide treated bed nets, residual insecticide spraying, preventative drugs, and treatment with combined drug therapy. Effective prevention and treatment efforts, plus advances in diagnostic testing, have greatly reduced both case numbers and mortality rates, but the development of resistance, including insecticide resistance in the mosquito vector population and drug resistance in the pathogen population present new challenges. A greater understanding of the underlying biology of the pathogen may allow for improved and more targeted interventions in the future.

written by Angela Saenz & Alireza Shokoohi

Dr. Miguel Altieri is a Chilean agronomist and entomologist that has dedicated his life and career to agroecology. He is currently an emeritus professor from the University of California, Berkeley, where he teaches sustainable management practices to enhance biological control on farms. He is also a part-time farmer in the slopes of the Colombian Andes and the co-director of CELIA (Centro Latinoamericano de Investigaciones Agroecológicas), an organization focused on teaching, extension, and outreach for small farmers and research for food production through biodiverse systems. |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

Department of Entomology

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

University of Maryland

4112 Plant Sciences Building

College Park, MD 20742-4454

USA

Telephone: 301.405.3911

Fax: 301.314.9290

RSS Feed

RSS Feed